Gene Deletion

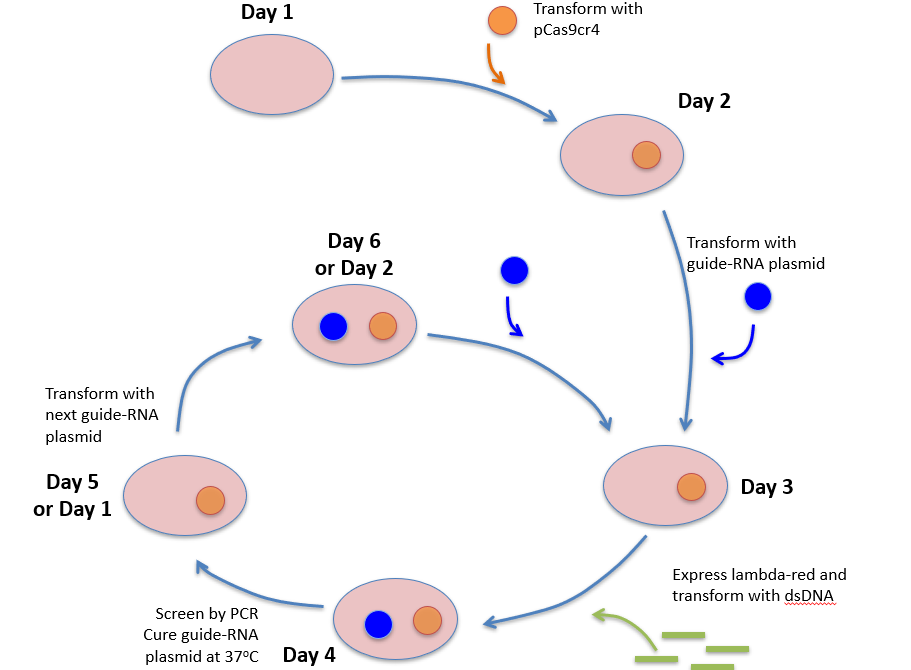

We first attempted the no-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) method to remove ldhA (lactate dehydrogenase-A) from the E. coli Nissle genome. No-SCAR is different from the traditional CRISPR system used in eukaryotes because it uses CRISPR to counterselect against the wild type DNA, theoretically leaving only mutant colonies on the plate. Cells are transformed with two plasmids carrying Cas9 and the guide RNA. Cells are then transformed again with DNA oligonucleotides that confer a mutation to the target site of the guide-RNA. Colonies are incubated on antibiotic plates and mutant bacteria survive while wild-type are killed off by the CRISPR-Cas9 complex. E. coli naturally lack an efficient double-strand-break-repair system and CRISPR-Cas9 engineering can kill off wild-type cells after genetic targeting by the specific guide-RNA. This method takes advantage of the lack of repair and targets colonies that have failed to mutate (i.e. no gene deletion) and induces cell death.

no-SCAR

However no-SCAR proved very difficult to manage in our specific E. coli Nissle chassis. Over one hundred bacterial colonies were screened for the deletion before we moved on to a different approach. This approach was not sustainable to rid one gene let alone the five carbon-draining genes in the short time we had left so we moved on.

Three groups: Control (C) Deletion (D) Mutation (M)The Control group was transformed with an oligonucleotide homologous to a region of the genome outside of the guide RNA’s recognition (rpoB). The Deletion group was transformed with an oligo that caused a deletion of the entire ldhA gene. The Mutation group was transformed with an oligo that caused a stop mutation in the ldhA gene. Cas9 was induced via addition of anhydrous tetracycline on the right plate but not on the left, and 10-fold serial dilutions were made from the bottom of the plate to the top. No group had any order of magnitude of more killing than any other, implying that either recombination was not efficiently occurring or that crispr-Cas9 was not selectively killing wild-type bacteria as we had hoped.

We switched to the Datsenko-Wanner method. This technique utilizes antibiotic resistance replacement of the desired gene deletion. To accomplish this we used primers to amplify out a kanamycin resistance gene. This sequence was flanked upstream and downstream with regions of homology to the specific gene to remove. This amplified oligo was then used to recombineer a deletion and select for by kanamycin resistance. The resistance was necessary to remove so we used a FLP recombinase to 'flip' out the resistance gene. PCR and patching was used to confirm deletion. Within a week of switching, the frd operon (fumarate reductase) was successfully deleted though dozens of colonies had to be screened in order to find the correct mutant. From then on this was our chosen deletion method.

Datsenko-Wanner

1. Integrate Resistance Cassette

#1. Ladder #2. Wild type (5kb) #3. frd operon + frt-kanamycin-frt cassette (1.5kb)

2. Flip out Resistance Cassette

Frt-kanamycin cassette flipped out using the pcp20 plasmid encoded recombinase. The sample to the right of those two bands represents the previously integrated 1.5kb fragment.

The colonies with the confirmed removal of the Kan cassette were patched on kanamycin plates (pictured below). The plasmids we used, pCP20 and pKD46, had to be confirmed via patching that they're cured of the cell. This is done because unless the untransformed cell is sensitive for the antibiotic you're selecting it with, you wont be able to select for properly transformed cells. By plating the same colony on multiple antibiotic resistant plates, you can confirm that the cell is sensitive and resistant to respective antibiotics.

3. Patching

However, we discovered through HPLC that fumarate was still being produced at higher concentrations than what was predicted by our metabolic model. We went back to the sequence and discovered that frdA is present in two copies in the E. coli Nissle genome. Although the gel showed the gene to be deleted, we had not known that a duplication existed.The second operon existed internally to the primers we used to screen and the homologous regions we made to delete with, so is was neither deleted nor detected. Two deletions would have been necessary to channel the carbon flow away from fumarate.

We decided not to go forward with that option as our model showed that other genes would have more carbon flux impact if deleted.

Next to be deleted was ldhA which fortunately does not have a gene copy. This was validated by confirmation of fragment bands on a gel and lack of lactate production seen by HPLC measurements.

(Left) One colony had the 1.5kb kan-frt cassette integrated into its genome at the ldha location. Out of the 58 colonies screened for ldhA deletions, we found one that had it. Subsequent flipping out and loss of kanamycin resistance was successful.

Butyrate Assembly

Team members optimized the five gene sequences for E. coli Nissle 1917 for butyrate upregulation. The gene pathway was too long (5 kb) to be synthesized in one string so it was ordered as a gblock composed as two fragments. Synthesis was chosen over ordering the parts in a plasmid for cost efficiency. Butyrate fragment (BF) #1 contained atoB, hbd, and crt and BF #2 had ter and tesB. The ordered sequences were delivered with unintentional alterations that had extra copies of the Xbol digestion sites. This made it impossible to properly digest and ligate our gene fragments together, which is the typical way to assemble. A variety of other molecular techniques were attempted: (1) Overlap extension (2) Blunt Ligation of fragments #1 and #2.

The two fragments had regions that were similar to each other (overlapping) of about 40 bases each.Theoretically, if run through enough cycles of PCR the two fragments would become one due to elongation over the overlapping region (overlap extension). Even though a 5.3 kb band was visible after 12 cycles of overlap extension PCR, it was not possible to amplify this fragment to concentrations high enough to successfully assemble the part via Circular Polymerization Extension Cloning or restriction digestion into psb1C3 or other plasmids such as ptrC99A. This may have been due to poor primer binding, or due to the fact that our gBlocks were not ideal for PCR reactions.

We also attempted a blunt ligation of BF #1 and BF #2 into ptrc99A, to later be moved into psb1c3. These attempts also proved unsuccessful, as there were no bands in PCR reactions that screened for inserts.

Overlap PCR

Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning

After several months of work without any results, the Parts Registry and previous projects were searched for a solution. The Toulouse 2015 iGEM biobricks (BBa_K1587004 and BBa_K1587005) had four of the five enzymes contained in our gblock, but no ter. We attempted to improve the butyrate synthesis pathway BBa_K1587004. A critical analysis of this pathway reveals that the ccr gene, which catalyzes the reduction of crotonyl-coA to butyryl-CoA, is NADPH-dependent. Without an enzyme that couples NADH to NADPH, this pathway will not be functional for butyrate production. Our initial rationale for gene deletions was to force E. coli to produce butyrate with our synthetic pathway in order to maintain redox balance, but this would be impossible without an enzyme that catalyzes the reduction using NADH instead of NADPH. For this reason, we attempted to add the trans-enoyl reductase (ter) to their pathway via restriction digestion to form a complete redox balanced pathway that could be driven further via gene deletions.

Thus, it was feasible to add our ter onto their assembly in order to complete the pathway. We successfully used PCR with primers containing the iGEM prefix and suffix to clone out ter from BF #2. This was followed by successful circular polymerase extension cloning into the psb1C3 backbone and transformation into E. coli Nissle, resulting in our first biobrick of ter without a promoter. We attempted to add the pCAT and pBAD promoters to this via 3A assembly from the distribution kit, but such attempts did not work and there was not enough time to troubleshoot before the parts deadline. We did confirm that our ter-psb1c3 part is RFC 10 compliant via restriction digestion, and have submitted it to the registry for future teams to use.

We did not stop trying. Below is our last attempt at assembling a functional butyrate pathway. This time.....we believe it worked!!! See Results/Demonstrate for more detail.

Final Butyrate Pathway Assembly Method

FimH Addition

Red fluorescent protein (RFP) (BBa_J04450) was inserted downstream of the engineered FimH via 3A assembly. This part was then moved back into pSB1C3 using Ecor-I and Pst-I digestion. PCR and restriction digestion were used to confirm that this part was RFC 10 compliant. Visual confirmation of the RFP gene expression is seen in the pictures below. Red-pink colonies appeared on a culture plate after several days of growth.

Tube #1 - LB only

Tube #2 -wild-type E. coli Nissle

Tube #3 - E. coli Nissle transformed with FimH-RFP (in one plasmid)

Tube #4 - E. coli Nissle transformed with RFP and FIMH (two separate plasmids)

Our FimH-RFP part BBa_K267000 is clearly less "red" than FimH and RFP cotransformed onto separate plasmids. However our submitted part is useful in assays as seen below. This occurrence is likely due to genetic context dependency.

This test was performed on Caco-2 cells which are an immortal line of epithelial corectal cancer cells. Characterization assays showed that E. coli Nissle expressing our part were found closer to Caco-2 cells than colonies expressing RFP only, indicating that the Harvard Biodesign BBa_K1580011 is intact and functional. Box (A) shows Caco-2 cells alone, and Box (B) and (C) show Caco-2 cells infected with engineered Nissle 1917. In Box (C) the 137 isoform failed to result in binding to Caco-2 cells. Box (B) shows the 49 isoform successfully bound to Caco-2 cells in suspension, concluding that the expression of RFP and fimH 49 did not interfere with each other, and robustly allowed for the visualization of engineered Nissle 1917 using our method. As an extra control, Box (D) shows wild type Nissle 1917 and Caco-2 cells. Physical binding was not seen in this group either.

Box (E) and Box (F) are the same cells but without prior addition of RFP by rhamnose. They show no binding because fimH is not being induced.This part was sequenced however the output was not added to the parts registry because we believe the data to be of poor quality due to improper primer binding. However the order of the composite part was confirmed by detection of FimH in many of the sequence reads near the beginning while RFP was not detected in the start region.

References

1. Reisch CR, Prather KLJ. Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering (no-SCAR) in Escherichia coli, an Easy-to-Use System for Genome Editing. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2017 Jan 5;117:31.8.1-31.8.20. doi: 10.1002/cpmb.29.

2. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL.One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Jun 6;97(12):6640-5