| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{NEU_China_A}} | {{NEU_China_A}} | ||

| − | <html> | + | {{Template:NEU_China_A/header}} |

| + | <html lang="en"> | ||

| + | <!-- header --> | ||

| + | <style> | ||

| + | .borderleft { | ||

| + | border-style: none none none solid; | ||

| + | border-color: #03a9f4; | ||

| + | border-width: 5px; | ||

| + | padding-left:15px; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | p { | ||

| + | line-height: 30px; | ||

| + | font-size:17px; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | .tooltip { | ||

| + | font-size: 12px; | ||

| + | color: #000 | ||

| + | } | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | .tooltip strong { |

| + | font-weight: 700 | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | .link-color{ | ||

| + | color:#03a9f4 !important; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | </style> | ||

| + | <div class="container"> | ||

| + | <br/><br/> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/cb/T--NEU_China_A--homepage-pic2-img.png" alt="Overview" | ||

| + | onscroll="Materialize.fadeInImage('#image-test')" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <h3 class = "header"> <span class = "light-blue-text">Overview</span> </h3> | ||

| + | <p class="card-panel hoverable"> | ||

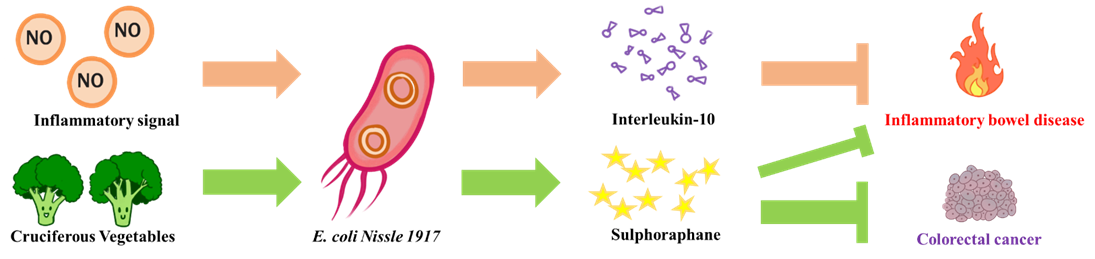

| + | The goal of NEU_China_A this year is to design a biological system aiming to alleviate intestinal inflammatory diseases and prevent potential colorectal cancer. We chose E. coli Nissle 1917 as our chassis, a probiotic that is safe for humans. On the one hand, when it senses an inflammatory signal in the intestine, it releases an anti-inflammatory compound (interleukin-10) to put out the fire in the intestines. On the other hand, it can release myrosinase to convert the glucosinolate contained in cruciferous vegetables into sulforaphane. The sulforaphane can both alleviate inflammation in the intestine and prevent colorectal cancer induced by chronic inflammation. | ||

| + | </p><br/><br/> | ||

| + | <p><strong>For details about our project background and introduction, please click to</strong><a class="link-color" href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:NEU_China_A/Description">Description</a></p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>For details of whole project design, please click to</strong><a class="link-color" href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:NEU_China_A/Design">Design</a></p> | ||

| + | <p >As a therapeutic project, we know that it is very difficult to verify the entire system in less than a year. We split the entire system into three core parts to verify separately: the nitric oxide sensor (nitric oxide is a marker of inflammation), protein transport and production, and the kill switch. In addition, we test them in DH5α and BL21. We believe that the success of these core parts will ultimately make the system work in the real world.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <span class="flow-text light-blue-text"> | ||

| + | 1.Nitric oxide sensor | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We constructed our NO sensor in the pCDFDuet-1 plasmid (Figure 1). Although the E. coli has native NorR expression, increasing its expression facilitates the elimination of stoichiometric imbalances between NorR in the genome and PnorV on the foreign plasmid, avoiding interference with the host's detoxification of nitric oxide. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 1. The construction of our NO sensor." src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/1/14/T--NEU_China_A--results-1.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | < | + | <br /> |

| − | < | + | <p class="borderleft"> |

| − | < | + | According to the results of the <a class="link-color" href="https://2016.igem.org/Team:ShanghaiTechChina_B/Project#NO_Sensor">ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team</a>, 100μM SNP aqueous solution can continuously release NO, and the NO concentration is stable at about 5.5μM. This concentration is the concentration of NO in patients with IBD and it is nearly 100 times higher than normal people. So, we can simulate the patient's inflammatory signal in vitro. In the subsequent test of the NO sensor, the final concentration of the SNP aqueous solution we added was 100 μM. |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | <p> | + | <br /> |

| − | + | <p class="borderleft"> | |

| − | </p> | + | We transformed the constructed plasmid of NO sensor into DH5α, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.2. After 1.5 h of growth at 37 ℃, the inducer IPTG and SNP aqueous solution were added. After 6 h at 37 ℃, 1 mL of the bacterial solution was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min (Figure 2). It can be seen that the NO released by the SNP aqueous solution can effectively activate the expression of the reporter gene. But to our surprise, the blue chromoprotein in group 1mM IPTG without SNP was also be activated. We have not yet figured out the reasons behind this phenomenon. But we speculate that it may be caused by leaky expression of promoter PnorV when the NorR overexpress. Due to this, we will use a weak promoter to express NorR in future engineered bacteria to avoid leakage. |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | <p> | + | <br /> |

| − | + | <div class="center-align"> | |

| − | </p> | + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 2. Pellets of bacteria transformed with constructed NO sensor plasmid after induction of 6h." |

| + | src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/07/T--NEU_China_A--results-2.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | From left to right: control, 0.5mM IPTG without SNP, 1mM IPTG without SNP, 0.5mM IPTG with 100μM SNP, 1mM IPTG with 100μM SNP. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft">Besides, during our participation in the 5th CCiC (Conference of China iGEMer Community), we communicated with the iGEM team SJTU-BioX-Shanghai. We learned that they detected colorectal cancer through the nitric oxide inducible promoter PyeaR, and at that time we were having trouble using nitric oxide to drive PnorV to transcribe our reporter. So, we also tested the effect of PyeaR (BBa_K381001) in the Distribution Kit (Figure 3). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We also tested the response of BBa_K381001 to NO in the Distribution Kit (Figure 3). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 3. The construction of BBa_K381001." src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/84/T--NEU_China_A--results-3.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We transformed the plasmid containing BBa_K381001 into DH5α, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.4. Then we took half as control and the other half added SNP aqueous solution and induced at 37 ℃ for 6 h. Then we detected the fluorescence using a microplate reader and a fluorescence microscope (Figure 4). We can see that PyeaR can also be effectively activated by NO with almost no leakage. In the future, we will compare the performance of PyeaR and PnorV in depth. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 4. The response to NO of BBa_K381001. " src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b3/T--NEU_China_A--results-4.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | Histogram of GFP fluorescence: LB control, without SNP, with 100μM SNP. B, GFP fluorescence image from top to bottom: without SNP, with 100μM SNP. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft">In conclusion, we have confirmed that the NO sensor in E. coli we built capable of responding to chemically produced nitric oxide in vitro. And we believe that as a naturally NO response mechanism in E. coli, the NO sensor we construct will also work in vivo. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Parts for this section: </strong> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817000">BBa_K2817000</a> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K381001">BBa_K381001</a> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <span class="flow-text light-blue-text"> | ||

| + | 2 Transport and Production | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | At the beginning of the experiment, we directly constructed the plasmids of YebF-IL10 and YebF-myrosinase, but the effect of extracellular detection was not satisfactory. During the participation in CCiC, iGEMer suggested that we first start from testing the performance of the secretory tag YebF, so we constructed the plasmid YebF-GFP shown in Figure 5A. To express IL10 and myrosinase, we constructed plasmids IL10-flag and myrosinase-his as shown in Figure 5B and Figure 5C. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 5. Production module construction." src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2a/T--NEU_China_A--results-5.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | <strong>A</strong>, the construction of our YebF-GFP using strong promoter. | ||

| + | <strong>B</strong>, the construction of IL10 production module. | ||

| + | <strong>C</strong>, the construction of myrosinase production module. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | When testing the validity of the secretory tag YebF, we transformed the constructed YebF-GFP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37 ℃. The supernatant was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was taken for fluorescence detection. The results are shown in the Figure 6. But we forgot to set up a positive control group. Due to time constraints, we have no time to repeat this experiment. But as a secretory tag used in both the literature and the iGEM team, we believe it can actually work. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 6. The fluorescence of overnight bacterial suspension." src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/92/T--NEU_China_A--results-6.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We transformed the IL10-flag plasmid into BL21, and incubated at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.2. After 2 h of growth at 37 ℃, IPTG was added and induced at 30 ℃ for 16 h. Then, the bacterial solution was lysed and the expression of IL10 was detected by western blot (Figure 7). We used the human IL10 sequence optimized by E. coli from the previous iGEM team (the original part is <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K554004">BBa_K554004</a>). So we have reason to believe that we have successfully expressed IL10. As a widely validated and used cytokine, we believe it can play an immunosuppressive role in vivo. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 7. Western blot analyses using a flag antibody on bacterial lysate to detect IL10." | ||

| + | src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/ac/T--NEU_China_A--results-7.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.5mM IPTG, Lane3: 1mM IPTG | ||

| + | induction for 16h at 30℃. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We transformed the plasmid of myrosinase-his into BL21, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight and diluted to OD = 0.2. After growth for 2 h at 37 ℃, different concentrations of IPTG were added and induced at 16 ℃ for 16 h. The bacterial cell lysis was then performed to detect the expression of myrosinase by SDS-PAGE (Figure 8). The sequence of the myrosinase enzyme was optimized based on the K12 strain and the position of the strip is almost correct, so we believe we have successfully expressed it. The myrosinase can convert glucosinolates contained in cruciferous vegetables into sulforaphane which has well-known anti-cancer activity. A literature earlier this year <a class="link-color" href="https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-017-0181-y">(https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-017-0181-y)</a> has validated the activity of myrosinase expressed by E. coli Nissle 1917 in vivo and in vitro. So we believe that the myrosinase we expressed can work. For more details about this transferase related information, please see our <a class="link-color" href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:NEU_China_A/Design">project design</a>. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 8. SDS-PAGE analyses on bacterial lysate to detect myrosinase." | ||

| + | src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/ae/T--NEU_China_A--results-8.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.25mM IPTG; Lane3: 0.5mM IPTG, Lane4: 0.75mM IPTG induction for 16h at 16℃. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Parts for this section: </strong> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817013">BBa_K2817013</a> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817002">BBa_K2817002</a> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817004">BBa_K2817004</a> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <span class="flow-text light-blue-text"> | ||

| + | 3.Kill Switch | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="s10 offset-s2"> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | When we use engineered bacteria to treat IBD, we need to do biocontainment work to avoid the release of engineered bacteria into the environment. Therefore, in our project, we designed a cold shock kill switch based on the toxin-antitoxin system mazEF, so we can kill our engineered E. coli when it escape from human body. We inserted the reporter gene amilCP into the pColdI plasmid to characterize the performance of the cold shock promoter PcspA (Figure 9A). Then we inserted maz-F into the pColdI plasmid to build our kill switch (Figure 9B). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 9. Kill switch module construction. " src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/de/T--NEU_China_A--results-9.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | <strong>A</strong>, the construction of PcspA-amilCP plasmid. | ||

| + | <strong>B</strong>, the construction of PcspA-mazF plasmid. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | We transformed the PcspA-amilCP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37℃. The overnight culture was diluted to OD = 0.2 and allowed to grow for 2 h at 37℃. It was then divided into different concentrations of IPTG at 16℃ and 37℃ for 6 h (Figure 10). It can be seen from the figure 11A that the reporter gene is efficiently expressed at low temperature, which indicates that the effective expression of the toxin gene mazF and the closed expression of the anti-toxin gene mazE at low temperature can kill our engineered bacteria in time. Although the cold shock promoter PcspA has a certain leakage at body temperature, the toxin is neutralized by the anti-toxin expressed at body temperature, so the effect is not significant. However, it is best to add a lacO site in the future to suppress leakage. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 10. Pellets of bacteria transformed with constructed PcspA-amilCP plasmid after induction of 6h." | ||

| + | src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/5/5a/T--NEU_China_A--results-10.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | From left to right: 37℃ without IPTG, 37℃ with 0.5mM IPTG, 37℃ with 1mM IPTG, 16℃ without IPTG, 16℃ | ||

| + | with 0.5mM IPTG, 16℃ with 1mM IPTG. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="borderleft"> | ||

| + | Next, we test the effect of mazF. We transformed the constructed PcspA-mazF plasmid into BL21, added 1 mM IPTG to the plate, and cultured at 16℃ for 16 h (Figure 11A). We then cultured BL21 transformed with the PcspA-mazF plasmid overnight at 16℃. After diluting to OD=0.2 on the next day, the cells were cultured at 16℃, and the OD value was measured every hour for 9 hours (Figure 11B). From Figure 11 below, you can see that our kill switch can work at low temperatures. Although some engineered bacteria still survive, we believe they will be effectively killed in the absence of nutritional support. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <div class="center-align"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" title="Figure 11. The effect of our killer gene under 16℃." | ||

| + | src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/05/T--NEU_China_A--results-11.png" /> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip center-align"> | ||

| + | <strong>A</strong>, the plate of BL21 with and without killer gene under induction. B, the growth curve of BL21 with and without killer gene under induction. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Parts for this section: </strong> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817012">BBa_K2817012</a> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <a class="link-color" href="http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K2817006">BBa_K2817006</a> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p class="card-panel hoverable">Finally, we are convinced the integration of these successful module will guarantee the effective work of our engineered system in E. coli under realistic conditions.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <script type="text/javascript"> | |

| − | + | // 初始化navBar | |

| − | + | $(document).ready(function () { | |

| + | $('.sidenav').sidenav(); | ||

| + | $(".dropdown-trigger").dropdown(); | ||

| + | $('.collapsible').collapsible(); | ||

| + | $('.parallax').parallax(); | ||

| + | }); | ||

| + | </script> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Revision as of 14:30, 16 October 2018

-

folder_openProject

-

placeLab

-

detailsParts

-

lightbulb_outlineHP

-

peopleTeam

Overview

The goal of NEU_China_A this year is to design a biological system aiming to alleviate intestinal inflammatory diseases and prevent potential colorectal cancer. We chose E. coli Nissle 1917 as our chassis, a probiotic that is safe for humans. On the one hand, when it senses an inflammatory signal in the intestine, it releases an anti-inflammatory compound (interleukin-10) to put out the fire in the intestines. On the other hand, it can release myrosinase to convert the glucosinolate contained in cruciferous vegetables into sulforaphane. The sulforaphane can both alleviate inflammation in the intestine and prevent colorectal cancer induced by chronic inflammation.

For details about our project background and introduction, please click toDescription

For details of whole project design, please click toDesign

As a therapeutic project, we know that it is very difficult to verify the entire system in less than a year. We split the entire system into three core parts to verify separately: the nitric oxide sensor (nitric oxide is a marker of inflammation), protein transport and production, and the kill switch. In addition, we test them in DH5α and BL21. We believe that the success of these core parts will ultimately make the system work in the real world.

We constructed our NO sensor in the pCDFDuet-1 plasmid (Figure 1). Although the E. coli has native NorR expression, increasing its expression facilitates the elimination of stoichiometric imbalances between NorR in the genome and PnorV on the foreign plasmid, avoiding interference with the host's detoxification of nitric oxide.

According to the results of the ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team, 100μM SNP aqueous solution can continuously release NO, and the NO concentration is stable at about 5.5μM. This concentration is the concentration of NO in patients with IBD and it is nearly 100 times higher than normal people. So, we can simulate the patient's inflammatory signal in vitro. In the subsequent test of the NO sensor, the final concentration of the SNP aqueous solution we added was 100 μM.

We transformed the constructed plasmid of NO sensor into DH5α, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.2. After 1.5 h of growth at 37 ℃, the inducer IPTG and SNP aqueous solution were added. After 6 h at 37 ℃, 1 mL of the bacterial solution was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min (Figure 2). It can be seen that the NO released by the SNP aqueous solution can effectively activate the expression of the reporter gene. But to our surprise, the blue chromoprotein in group 1mM IPTG without SNP was also be activated. We have not yet figured out the reasons behind this phenomenon. But we speculate that it may be caused by leaky expression of promoter PnorV when the NorR overexpress. Due to this, we will use a weak promoter to express NorR in future engineered bacteria to avoid leakage.

From left to right: control, 0.5mM IPTG without SNP, 1mM IPTG without SNP, 0.5mM IPTG with 100μM SNP, 1mM IPTG with 100μM SNP.

Besides, during our participation in the 5th CCiC (Conference of China iGEMer Community), we communicated with the iGEM team SJTU-BioX-Shanghai. We learned that they detected colorectal cancer through the nitric oxide inducible promoter PyeaR, and at that time we were having trouble using nitric oxide to drive PnorV to transcribe our reporter. So, we also tested the effect of PyeaR (BBa_K381001) in the Distribution Kit (Figure 3).

We also tested the response of BBa_K381001 to NO in the Distribution Kit (Figure 3).

We transformed the plasmid containing BBa_K381001 into DH5α, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.4. Then we took half as control and the other half added SNP aqueous solution and induced at 37 ℃ for 6 h. Then we detected the fluorescence using a microplate reader and a fluorescence microscope (Figure 4). We can see that PyeaR can also be effectively activated by NO with almost no leakage. In the future, we will compare the performance of PyeaR and PnorV in depth.

Histogram of GFP fluorescence: LB control, without SNP, with 100μM SNP. B, GFP fluorescence image from top to bottom: without SNP, with 100μM SNP.

In conclusion, we have confirmed that the NO sensor in E. coli we built capable of responding to chemically produced nitric oxide in vitro. And we believe that as a naturally NO response mechanism in E. coli, the NO sensor we construct will also work in vivo.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817000

BBa_K381001

At the beginning of the experiment, we directly constructed the plasmids of YebF-IL10 and YebF-myrosinase, but the effect of extracellular detection was not satisfactory. During the participation in CCiC, iGEMer suggested that we first start from testing the performance of the secretory tag YebF, so we constructed the plasmid YebF-GFP shown in Figure 5A. To express IL10 and myrosinase, we constructed plasmids IL10-flag and myrosinase-his as shown in Figure 5B and Figure 5C.

A, the construction of our YebF-GFP using strong promoter. B, the construction of IL10 production module. C, the construction of myrosinase production module.

When testing the validity of the secretory tag YebF, we transformed the constructed YebF-GFP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37 ℃. The supernatant was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was taken for fluorescence detection. The results are shown in the Figure 6. But we forgot to set up a positive control group. Due to time constraints, we have no time to repeat this experiment. But as a secretory tag used in both the literature and the iGEM team, we believe it can actually work.

We transformed the IL10-flag plasmid into BL21, and incubated at 37 ℃ overnight to dilute to OD = 0.2. After 2 h of growth at 37 ℃, IPTG was added and induced at 30 ℃ for 16 h. Then, the bacterial solution was lysed and the expression of IL10 was detected by western blot (Figure 7). We used the human IL10 sequence optimized by E. coli from the previous iGEM team (the original part is BBa_K554004). So we have reason to believe that we have successfully expressed IL10. As a widely validated and used cytokine, we believe it can play an immunosuppressive role in vivo.

Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.5mM IPTG, Lane3: 1mM IPTG induction for 16h at 30℃.

We transformed the plasmid of myrosinase-his into BL21, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight and diluted to OD = 0.2. After growth for 2 h at 37 ℃, different concentrations of IPTG were added and induced at 16 ℃ for 16 h. The bacterial cell lysis was then performed to detect the expression of myrosinase by SDS-PAGE (Figure 8). The sequence of the myrosinase enzyme was optimized based on the K12 strain and the position of the strip is almost correct, so we believe we have successfully expressed it. The myrosinase can convert glucosinolates contained in cruciferous vegetables into sulforaphane which has well-known anti-cancer activity. A literature earlier this year (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-017-0181-y) has validated the activity of myrosinase expressed by E. coli Nissle 1917 in vivo and in vitro. So we believe that the myrosinase we expressed can work. For more details about this transferase related information, please see our project design.

Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.25mM IPTG; Lane3: 0.5mM IPTG, Lane4: 0.75mM IPTG induction for 16h at 16℃.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817013

BBa_K2817002

BBa_K2817004

When we use engineered bacteria to treat IBD, we need to do biocontainment work to avoid the release of engineered bacteria into the environment. Therefore, in our project, we designed a cold shock kill switch based on the toxin-antitoxin system mazEF, so we can kill our engineered E. coli when it escape from human body. We inserted the reporter gene amilCP into the pColdI plasmid to characterize the performance of the cold shock promoter PcspA (Figure 9A). Then we inserted maz-F into the pColdI plasmid to build our kill switch (Figure 9B).

A, the construction of PcspA-amilCP plasmid. B, the construction of PcspA-mazF plasmid.

We transformed the PcspA-amilCP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37℃. The overnight culture was diluted to OD = 0.2 and allowed to grow for 2 h at 37℃. It was then divided into different concentrations of IPTG at 16℃ and 37℃ for 6 h (Figure 10). It can be seen from the figure 11A that the reporter gene is efficiently expressed at low temperature, which indicates that the effective expression of the toxin gene mazF and the closed expression of the anti-toxin gene mazE at low temperature can kill our engineered bacteria in time. Although the cold shock promoter PcspA has a certain leakage at body temperature, the toxin is neutralized by the anti-toxin expressed at body temperature, so the effect is not significant. However, it is best to add a lacO site in the future to suppress leakage.

From left to right: 37℃ without IPTG, 37℃ with 0.5mM IPTG, 37℃ with 1mM IPTG, 16℃ without IPTG, 16℃ with 0.5mM IPTG, 16℃ with 1mM IPTG.

Next, we test the effect of mazF. We transformed the constructed PcspA-mazF plasmid into BL21, added 1 mM IPTG to the plate, and cultured at 16℃ for 16 h (Figure 11A). We then cultured BL21 transformed with the PcspA-mazF plasmid overnight at 16℃. After diluting to OD=0.2 on the next day, the cells were cultured at 16℃, and the OD value was measured every hour for 9 hours (Figure 11B). From Figure 11 below, you can see that our kill switch can work at low temperatures. Although some engineered bacteria still survive, we believe they will be effectively killed in the absence of nutritional support.

A, the plate of BL21 with and without killer gene under induction. B, the growth curve of BL21 with and without killer gene under induction.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817012

BBa_K2817006

Finally, we are convinced the integration of these successful module will guarantee the effective work of our engineered system in E. coli under realistic conditions.