Megan-Jones (Talk | contribs) |

Megan-Jones (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

<h2>Patents</h2> | <h2>Patents</h2> | ||

<p>Early on, the team had questions about the possibility of patenting the new, invented system. Early advice was sought from one of the team mentors (Daniel Winter), which essentially stated that genetic sequences were not patentable or protectable, and therefore, there was no possibility of patenting the invention. However, the advice lacked clarity as to the actual reasons why that was so. Further research was then conducted into the relevant legal decisions establishing genetic sequence protection law, particularly the High Court of Australia decision in <i>Myriad Genetics v D’Arcy</i><sup><a href=#references>2</a></sup>. Such research later showed that in actuality, it was the DNA sequence of the proteins which was not protectable – rather than the actual structure and design of the scaffold<sup><a href=#references>2</a>; <a href=#references>8</a>; <a href=#references>9</a></sup>. There is an equivalent US decision as well; <i>Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics</i>, although the scope of protection available differs between the two decisions<sup><a href=#references>10</a></sup>. Dr Alexandra George (Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Intellectual Property) was also consulted regarding some of the particular aspects of the law in order for the team to then evaluate if our invention would fall under the protected category. Given the potential patenting issues, we decided not to proceed with trying to patent the invention, and refocused the project as a foundational technology designed to be accessible to all. The legal reason behind this decision comes from the lack of ‘novelty’ once sequences are removed from contention<sup><a href=#references>9</a></sup>. | <p>Early on, the team had questions about the possibility of patenting the new, invented system. Early advice was sought from one of the team mentors (Daniel Winter), which essentially stated that genetic sequences were not patentable or protectable, and therefore, there was no possibility of patenting the invention. However, the advice lacked clarity as to the actual reasons why that was so. Further research was then conducted into the relevant legal decisions establishing genetic sequence protection law, particularly the High Court of Australia decision in <i>Myriad Genetics v D’Arcy</i><sup><a href=#references>2</a></sup>. Such research later showed that in actuality, it was the DNA sequence of the proteins which was not protectable – rather than the actual structure and design of the scaffold<sup><a href=#references>2</a>; <a href=#references>8</a>; <a href=#references>9</a></sup>. There is an equivalent US decision as well; <i>Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics</i>, although the scope of protection available differs between the two decisions<sup><a href=#references>10</a></sup>. Dr Alexandra George (Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Intellectual Property) was also consulted regarding some of the particular aspects of the law in order for the team to then evaluate if our invention would fall under the protected category. Given the potential patenting issues, we decided not to proceed with trying to patent the invention, and refocused the project as a foundational technology designed to be accessible to all. The legal reason behind this decision comes from the lack of ‘novelty’ once sequences are removed from contention<sup><a href=#references>9</a></sup>. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 15:55, 16 October 2018

Law and Regulation

Overview

The legal frameworks surrounding synthetic biology are critically important because they determine what type of research can be undertaken, by selecting for research that is legally allowable, available and has potential commercial implications. However, scientists often fail to effectively lobby for frameworks that support their research needs whilst the current law remains inadequate1

.Our UNSW team discovered, as part of our foray into commercialisation and due diligence on our scaffold elements, that biotechnological patent law is difficult to comprehend from the scientific perspective. In Australia particularly, the legal test for patents is long and convoluted, and requires a thorough understanding of previous cases1. However, our team successfully interpreted the law to conclude that our scaffold was not patentable (reinforcing our modular ‘Foundational Advance’ technology approach) and that we could use our preferred protein-protein bonding mechanism.

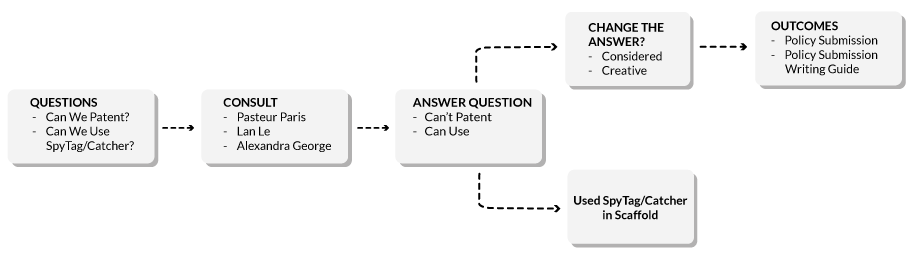

Considering this context, the UNSW team has come up with a creative solution – we have created a scientist’s guide to writing a policy proposal for government change, and written an example submission. We have also documented our discussions with various stakeholders, including the pharmaceutical industry, intellectual property academics, the UNSW Law Society, and the 2018 Pasteur Paris iGEM team.

Figure 1: Flowchart diagram of the legal processes undertaken by UNSW iGEM and the outcomes.

Relevance

The legal sphere may seem divorced from the practice of science in the laboratory, but in reality, they are closely intertwined, with three key points of intersection.

Commercialisation

The law can grant protection over ‘inventions’ made by scientists3. The protection the law grants can then allow the invention to be commercialised, and incentivises companies to invest in research to get a competitive advantage in the market – without fear of unmitigated copying. The law aims to encourage and assist innovation, instead of stifling it, by allowing market forces (and individual scientists) to capitalise on invention.

It also means that the research with the most funding is typically the research which is the most potentially lucrative – research which can present solutions to problems (like cancer) that affect wealthier societies who can pay more for medicine. This is as opposed to research for diseases almost exclusively present in poorer nations (like dengue).

Our team faced this issue – foundational technologies like the Assemblase system did not fit many of the grant opportunities that were available, being for things much closer to practical use. It did also mean we chose really practical enzymes for our model.

Accessibility & Availability

The law’s protection comes with a stipulation that the protected invention is revealed to the public. As a result, the public has access to that idea once the protected timeframe is over4.

It also means that researchers can, in the future, build off that idea to have higher quality research. Disclosure also means that scientists may choose to stop research in a particular area, and refocus on another.

However, that means that the law can render certain ideas inaccessible for a number of years. The challenge here is that science is a collaborative process, building on the research of others; and a period of years can stifle development and innovation.

Our team faced issues surrounding the availability of the protein SpyTag/Catcher system, because of its legal protection. However, these issues were avoided thanks to the research locations (and protection) being in two different jurisdictions.

Grants & Ethics Approval

Legal approval is being introduced as a preliminary requirement for research grant applications within Australia, similar to Europe. The grants we received were not dependent on ethics approval; however, we question whether they should be.

The availability of grant money to fund the research also determines what projects can be undertaken – a project ineligible for grant money is far less likely to go ahead.

There is also a correlation between the likely patentability of an invention, or area of science, and the amount of research funding which goes into the area. The Australian Bureau of Industry Economics 1994 Report stated that legal protection seems to ‘increase the incentive for investment in research and development, in a reasonably cost effective way’, and there has not been any significant change from this position in Australia5. More evidence of this correlation comes from the US, where 80% of the money spent on non-commercial pharmaceutical research comes from public sources6; 7.

Considered Analysis

The Assemblase system has posed a number of legal challenges for the team, with these challenges arising from the very beginning of the project.

Patents

Early on, the team had questions about the possibility of patenting the new, invented system. Early advice was sought from one of the team mentors (Daniel Winter), which essentially stated that genetic sequences were not patentable or protectable, and therefore, there was no possibility of patenting the invention. However, the advice lacked clarity as to the actual reasons why that was so. Further research was then conducted into the relevant legal decisions establishing genetic sequence protection law, particularly the High Court of Australia decision in Myriad Genetics v D’Arcy2. Such research later showed that in actuality, it was the DNA sequence of the proteins which was not protectable – rather than the actual structure and design of the scaffold2; 8; 9. There is an equivalent US decision as well; Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics, although the scope of protection available differs between the two decisions10. Dr Alexandra George (Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, Intellectual Property) was also consulted regarding some of the particular aspects of the law in order for the team to then evaluate if our invention would fall under the protected category. Given the potential patenting issues, we decided not to proceed with trying to patent the invention, and refocused the project as a foundational technology designed to be accessible to all. The legal reason behind this decision comes from the lack of ‘novelty’ once sequences are removed from contention9.

SpyTag/Catcher

Further patenting issues were encountered when the team decided to use SpyTag/Catcher and SnoopTag/Catcher as part of the scaffold. Legal research revealed that SpyTag/Catcher was patented in the US, but we could not find an Australian patent.11 This meant that we could use the SpyTag/Catcher system (which we did), as neither intellectual property provisions in the bilateral Australia - USA free trade agreement, nor those in the worldwide TRIPPS treaty, make US patents enforceable in Australia. 12; 13 Both agreements are more concerned with ensuring that the requirements for patenting, and protections offered once patents are granted, are similar internationally. As a result, our project used the SpyTag/Catcher system instead of the unpatented SdyTag/Catcher system, which was a better result as SdyTag/Catcher is much more cross-reactive with SnoopTag/Catcher.14 However, given the extensive research that had to be conducted to arrive at this position, the team began to consider how we might be able to push for systemic change.

Funding

As a result, consultations were sought with Lan Le (Research Ethics and Compliance Support) and Brad Walsh (CEO of Minomic International Ltd., which can be read about in our Journal. These consultations, in addition to speaking with Carl Stubbings (Head of Commercialisation, Minomic International Ltd.) at our team’s symposium, brought to our attention one other important impact legal protection has on science – it plays a major role in determining to which research money flows. Lan spoke about how legal (and ethics) approval was becoming a prerequisite for any grant funding, while Brad and Carl spoke about how legal protection allows them to capitalise on their investment into research – which is essential for them to have more funds to reinvest in research. Further research into this area revealed that the link between possible legal protection and funding is quite substantial. 6; 7 For our iGEM team, in applying for grants we found that our research wasn’t eligible for many opportunities, with substantially more opportunities available for research into direct medical applications, where there is a better chance of making a profit.

Figure 2: UNSW iGEM team meeting with Brad Walsh - CEO Minomic.

Creative Options: Policy Submissions

As a result, our team is convinced that the current balance between legal protectionism and encouraging innovation is off – one more voice in what is a continuing public policy debate in Australia.1 However, in considering how we could creatively contribute our voice and experience to the conversation, the team has discovered a ‘missing link’ of communication between science and the law, despite their many points of intersection. Scientific researchers outside of big corporations often do not contribute to the debate about how to best construct the law which they use every day – with the clearest example being the 2016 Intellectual Property Arrangements public inquiry receiving only two submissions from this group of scientists out of 620 pre- and post-report submissions. One possible way to re-establish this link is by writing to government, which is why the UNSW team’s creative solution was to write a policy submission guide and example submission.

Figure 3: Screenshot from a Skype call conducted between UNSW Australia and Pasteur Paris.

The policy submission, and suggestions for improvement, were critically evaluated and analysed in light of comments from Dr Alexandra George and the Pasteur Paris iGEM team. The Pasteur team particularly gave us insight into the differences between the civil law European regime and the Australian process, and Dr Alexandra George also gave insight into how the French system’s benefits are replicated here, but in a slightly different way.

Integration

The team’s research into the legal frameworks and implications on scientific research has affected the direction of our project. Firstly, it affected the decision of whether to patent the Assemblase system, by providing the framework to discuss the likelihood of a successful protection claim. As legal information gathered suggested that a patent was an unlikely outcome, we refocused the system onto modularity, using ‘ideal’ test enzymes. It also affected the way we consulted with other academics and people in industry, as we were more open with our ideas, and they could give us better feedback (being more directed towards the project).

Figure 4: The Assemblase scaffold with the Tag/Catcher systems.

Secondly, it affected the decision of which covalent protein attachment system was going to be chosen to use with the scaffold. Initial legal research had made us aware of the patent system, and further research was undertaken to establish whether an Australian patent was held for the system we wanted to use. We also researched whether that patent would stop our use of the system (educational exceptions to patents) and whether a US patent which did exist would stop our use of the system. Fortunately, using the research we came to a conclusion that the best systems to use (SpyTag/Catcher and SnoopTag/Catcher) were not protected in Australia, and that we could use them.5; 7; 8 The legal information gathered also led us to present an alternative in case of protection; the use of SnoopTag/Catcher and SdyTag/Catcher systems, being that these were not patented in both relevant countries of the United States and Australia.

There were also several indirect effects of legal systems on our project. Namely, the availability of certain methodologies in sufficient detail to allow them to be replicated within the modelling aspect of the project. It seemed that in some of the key papers, writers were trying to patent part of their research, and so did not publish very many details on their method – which proved to be challenging when our team tried to replicate part of their research using our enzymes. Additionally, it appears that the legal system fed into the lack of funding opportunities available; as outlined above, the lack of legal protection is associated with a lack of funding opportunities, particularly from independent companies, as they look for inventions which can give them a commercial edge in the market.5; 6

Outcomes

- How to Write a Policy Submission (Guide for Scientists).

- Example Policy Submission.

- Public discussion on the way law affects science;

- Symposium on the Australian Synthetic Biology Landscape.

- Presentation to an Environmental Humanities university course.

References

- Productivity Commission 2016, Intellectual Property Arrangements, Inquiry Report No. 78, Canberra.

- D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics (2015) 258 CLR 334 [20].

- N V Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 655.

- Patents Act 1990 (Cth).

- Andrew Stewart et al, Intellectual Property in Australia (Lexis Nexis Butterworths, 6th ed, 2018).

- Donald W Light and Joel R Lexchin, ‘Pharmaceutical research and development: what do we get for all that money?’ (2012) 343 British Medical Journal 4348.

- United States Congressional Budget Office, United States Congress, Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry (2006), 7.

- CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 28 IPR 481.

- Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253.

- Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics Inc (2013) 569 US 12-389.

- Powell, D. and Tsourkas, A. (2016). Spycatcher and spytag: universal immune receptors for t cells. WO2017112784A1.

- US Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act 2004 (Cth) implementing the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement.

- Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement (1993).

- Yajie Liu et al, ‘Tuning SpyTag–SpyCatcher mutant pairs toward orthogonal reactivity encryption’ (2017) 8 Chemical Science 6577-6582.