| (22 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<html lang="en"> | <html lang="en"> | ||

<!-- header --> | <!-- header --> | ||

| + | <style> | ||

| + | .row a { | ||

| + | text-decoration: underline; | ||

| + | color: #03a9f4; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | </style> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <style>.blu{background-color:#6D8AC0 !important;box-shadow:0px 3px 1px #6D8AC0 !important} h2{font-size:100px;}</style> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="section hold"></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="position:absolute;top: 20;width:100%"> | ||

| + | <div class="row "> | ||

| + | <h2 style="padding-left:200px; padding-top:calc(100vh - 250px)">Design</h2> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="homeheight"> | ||

| + | <div class="parallax-container homeheight"> | ||

| + | <div class="parallax"> | ||

| + | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/e/ef/T--NEU_China_A--desigin.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<body class="white"> | <body class="white"> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 41: | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/cb/T--NEU_China_A--homepage-pic2-img.png" | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/cb/T--NEU_China_A--homepage-pic2-img.png" | ||

alt="Overview" onscroll="Materialize.fadeInImage('#image-test')" /> | alt="Overview" onscroll="Materialize.fadeInImage('#image-test')" /> | ||

| − | <p class="card-panel hoverable">The goal of NEU_China_A | + | <p class="card-panel hoverable">The goal of NEU_China_A is to design a biological system to alleviate intestinal inflammatory diseases and prevent potential colorectal cancer. We chose the human probiotic <i>E. coli Nissle 1917</i>, as our chassis for constructing engineered probiotic. On the one hand, when the engineered bacteria senses an inflammatory signal in the intestine, it would release an anti-inflammatory compound (interleukin-10, IL-10) to reduce the intestinal inflammatory responses. On the other hand, engineered <i>E. coli</i> could secrete myrosinase to convert the cruciferous vegetables contained glucosinolate into sulforaphane that act as similar as IL-10 and prevent colorectal cancer induced by chronic inflammation. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 52: | ||

decided to use engineered bacteria to alleviate inflammatory bowel disease. Through literature review, | decided to use engineered bacteria to alleviate inflammatory bowel disease. Through literature review, | ||

we have found a bacteria that is clinically widely used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease | we have found a bacteria that is clinically widely used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease | ||

| − | - | + | - <i>E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN)</i> [1], which was isolated by German fetus Alfred Nissle during the First World |

War from the feces of a German soldier who was insusceptible to infectious diarrhea [2]. Alfred Nissle | War from the feces of a German soldier who was insusceptible to infectious diarrhea [2]. Alfred Nissle | ||

put the bacteria cultured on the agar plate into gelatin capsules and seals them with paraffin to make | put the bacteria cultured on the agar plate into gelatin capsules and seals them with paraffin to make | ||

| − | the drug Mutaflor [3]. Subsequent studies have confirmed that | + | the drug Mutaflor [3]. Subsequent studies have confirmed that <i>EcN</i> lacks virulence factors and has |

obvious probiotic properties, and is a safe and effective carrier for the treatment of inflammatory | obvious probiotic properties, and is a safe and effective carrier for the treatment of inflammatory | ||

| − | bowel disease [1]. | + | bowel disease [1]. <i>EcN</i> has excellent biofilm formation ability, so it has better |

colonization ability than other probiotic carriers, and it can inhibit the colonization of pathogens | colonization ability than other probiotic carriers, and it can inhibit the colonization of pathogens | ||

| − | [4]. In addition, | + | [4]. In addition, <i>EcN</i> can inhibit intestinal pathogens by secreting microcin and inducing |

| − | epithelial cells to secrete defensing-2 [5, 6]. Due to the excellent properties of | + | epithelial cells to secrete defensing-2 [5, 6]. Due to the excellent properties of <i>EcN</i>, in 2004, it |

was recommended by the German Society of Gastroenterology and Digestive Diseases (DGVS) as an | was recommended by the German Society of Gastroenterology and Digestive Diseases (DGVS) as an | ||

alternative to the UC standard for the treatment of mesalamine [7]. However, there are also some | alternative to the UC standard for the treatment of mesalamine [7]. However, there are also some | ||

| − | negative reports that EcN is not completely safe [8]. Therefore, we hope to use the modified EcN strain | + | negative reports that <i>EcN</i> is not completely safe [8]. Therefore, we hope to use the modified EcN strain |

SYNB1618 as our final chassis. SYNB1618 lacks colonization ability and is completely eliminated within | SYNB1618 as our final chassis. SYNB1618 lacks colonization ability and is completely eliminated within | ||

48 hours in the mouse model, so it is a safer chassis [9]. As a consequence of limited time and effort, | 48 hours in the mouse model, so it is a safer chassis [9]. As a consequence of limited time and effort, | ||

| − | in our experiments, we only used DH5α and BL21 strains to test the performance of our system. | + | in our experiments, we only used <i>DH5α and BL21</i> strains to test the performance of our system. |

Nevertheless, we hope that our engineered bacteria will be filled in capsules and taken orally to treat | Nevertheless, we hope that our engineered bacteria will be filled in capsules and taken orally to treat | ||

IBD in the future. | IBD in the future. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <div class="light-blue-text"> |

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Schultz M. Clinical use of E. coli Nissle 1917 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2008, 14(7): 1012-1018.<br/> |

| − | [2] Nissle A. Die antagonistische Behandlung chronischer Darmstoerungen mit Colibakterien [The antagonistic therapy of chronic intestinal disturbances]. Med Klinik. 1918:29–30. | + | [2] Nissle A. Die antagonistische Behandlung chronischer Darmstoerungen mit Colibakterien [The antagonistic therapy of chronic intestinal disturbances]. Med Klinik. 1918:29–30.<br/> |

| − | [3] Nissle A. Weiteres ueber die Grundlagen und Praxis der Mutaflorbehandlung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1925;44:1809–1813. | + | [3] Nissle A. Weiteres ueber die Grundlagen und Praxis der Mutaflorbehandlung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1925;44:1809–1813.<br/> |

| − | [4] Hancock V, Dahl M, Klemm P: Probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 outcompetes intestinal pathogens during biofilm formation. J Med Microbiol 2010; 59: 392–399. | + | [4] Hancock V, Dahl M, Klemm P: Probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 outcompetes intestinal pathogens during biofilm formation. J Med Microbiol 2010; 59: 392–399.<br/> |

| − | [5] Sassonecorsi M, Nuccio S P, Liu H, et al. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut[J]. Nature, 2016, 540(7632):280-283. | + | [5] Sassonecorsi M, Nuccio S P, Liu H, et al. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut[J]. Nature, 2016, 540(7632):280-283.<br/> |

| − | [6] Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, et al. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–2407. | + | [6] Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, et al. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–2407.<br/> |

| − | [7] Hoffmann CJ, Zeitz M, Bischoff SC, et al. [Diagnosis and therapy of ulcerative colitis: results of an evidence based consensus conference by the German society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the competence network on inflammatory bowel disease.] Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:979–983. | + | [7] Hoffmann CJ, Zeitz M, Bischoff SC, et al. [Diagnosis and therapy of ulcerative colitis: results of an evidence based consensus conference by the German society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the competence network on inflammatory bowel disease.] Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:979–983.<br/> |

| − | [8] Jacobi C A, Malfertheiner P. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor): New Insights into an Old Probiotic Bacterium[J]. Digestive Diseases, 2011, 29(6):600. | + | [8] Jacobi C A, Malfertheiner P. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor): New Insights into an Old Probiotic Bacterium[J]. Digestive Diseases, 2011, 29(6):600.<br/> |

| − | [9] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018). | + | [9] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018).<br/> |

| − | </ | + | </p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 90: | ||

sense the inflammatory signal and initiate the release of the drug. After comparing the | sense the inflammatory signal and initiate the release of the drug. After comparing the | ||

inflammatory sensors used in some iGEM teams, we selected the inflammatory sensor based on nitric | inflammatory sensors used in some iGEM teams, we selected the inflammatory sensor based on nitric | ||

| − | oxide molecules used by ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team. Nitric oxide is a natural signaling molecule | + | oxide molecules used by <a href="https://2016.igem.org/Team:ShanghaiTechChina_B/Project#NO_Sensor">ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team</a>. Nitric oxide is a natural signaling molecule |

of inflammation, and the concentration of intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD is | of inflammation, and the concentration of intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD is | ||

significantly increased [1]. It has been reported that the average concentration of nitric oxide in | significantly increased [1]. It has been reported that the average concentration of nitric oxide in | ||

| Line 78: | Line 98: | ||

location, thereby avoiding inappropriate output.</p> | location, thereby avoiding inappropriate output.</p> | ||

| − | <p>There are some natural nitric oxide sensors in E. coli, in which the enhancer binding protein NorR | + | <p>There are some natural nitric oxide sensors in <i>E. coli</i>, in which the enhancer binding protein NorR |

is specific and can only react with nitric oxide and cannot interact with other nitrogen forms [3]. | is specific and can only react with nitric oxide and cannot interact with other nitrogen forms [3]. | ||

NorR binds to three conserved sites on the NorV promoter (PnorV) via the C-terminal HTH domain. | NorR binds to three conserved sites on the NorV promoter (PnorV) via the C-terminal HTH domain. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 109: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3f/T--NEU_China_A--fig3.jpg"> | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3f/T--NEU_China_A--fig3.jpg"> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip"> | ||

| + | <strong>Figure 1. Engineered bacteria with inflammation sensor.</strong> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

<div class="borderleft"> | <div class="borderleft"> | ||

| − | <p>In our inflammation sensor, we used two parts which are NorR and PnorV. GFP and amilCP were selected | + | <p><i>In our inflammation sensor, we used two parts which are NorR and PnorV.</i> GFP and amilCP were selected |

| − | as our reporter genes. Although the E. coli host has native NorR expression, increasing its | + | as our reporter genes. Although the <i>E. coli</i> host has native NorR expression, increasing its |

expression facilitates the elimination of stoichiometric imbalances between NorR in the genome and | expression facilitates the elimination of stoichiometric imbalances between NorR in the genome and | ||

PnorV on the foreign plasmid, avoiding interference with the host's release of nitric oxide [5]. We | PnorV on the foreign plasmid, avoiding interference with the host's release of nitric oxide [5]. We | ||

used the double expression plasmid pCDFDuet-1 to construct our sensor module. Placing NorR under | used the double expression plasmid pCDFDuet-1 to construct our sensor module. Placing NorR under | ||

| − | the control of the first T7 promoter, we are able to regulate its expression by IPTG induction. We | + | the control of the first <i>T7</i> promoter, we are able to regulate its expression by IPTG induction. We |

also replaced the second promoter with PnorV and added the reporter gene downstream which allows us | also replaced the second promoter with PnorV and added the reporter gene downstream which allows us | ||

to activate the expression of the reporter gene by adding nitric oxide. In addition, during our | to activate the expression of the reporter gene by adding nitric oxide. In addition, during our | ||

participation in the 5th CCiC, we communicated with the team of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. We | participation in the 5th CCiC, we communicated with the team of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. We | ||

| − | learned that they detected colorectal cancer through the nitric oxide-inducible promoter | + | learned that they detected colorectal cancer through the gene expression initiated by nitric oxide-inducible promoter PyeaR, when we were having trouble detecting the expression of the reporter gene GFP after using nitric oxide to drive PnorV. Meanwhile, we also tested the effect of PyeaR in response to nitric oxide.</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <div class="light-blue-text"> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Rachmilewitz D, Stamler J S, Bachwich D, et al. Enhanced colonic nitric oxide generation and nitric oxide synthase activity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease[J]. Gut, 1995, 36(5): 718-723.<br/> |

| − | [2] Ljung T, Herulf M, Beijer E, et al. Rectal nitric oxide assessment in children with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Indicator of ileocaecal and colorectal affection[J]. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 2001, 36(10): 1073-1076. | + | [2] Ljung T, Herulf M, Beijer E, et al. Rectal nitric oxide assessment in children with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Indicator of ileocaecal and colorectal affection[J]. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 2001, 36(10): 1073-1076.<br/> |

| − | [3] Tucker, N. P., D’Autreaux, B., Yousafzai, F. K., Fairhurst, S. A., Spiro, S., and Dixon, R. (2008) Analysis of the nitric oxide-sensing non-heme iron center in the NorR regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 908−918. | + | [3] Tucker, N. P., D’Autreaux, B., Yousafzai, F. K., Fairhurst, S. A., Spiro, S., and Dixon, R. (2008) Analysis of the nitric oxide-sensing non-heme iron center in the NorR regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 908−918.<br/> |

| − | [4] Bush, M., Ghosh, T., Tucker, N., Zhang, X., and Dixon, R. (2011) Transcriptional regulation by the dedicated nitric oxide sensor, NorR: a route towards NO detoxification. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 289−293. | + | [4] Bush, M., Ghosh, T., Tucker, N., Zhang, X., and Dixon, R. (2011) Transcriptional regulation by the dedicated nitric oxide sensor, NorR: a route towards NO detoxification. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 289−293.<br/> |

| − | [5] Archer, E.J., Robinson, A.B. & Suel, G.M. Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS Synth. Biol. 1, 451–457 (2012). | + | [5] Archer, E.J., Robinson, A.B. & Suel, G.M. Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS Synth. Biol. 1, 451–457 (2012).<br/> |

| − | </ | + | </p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 129: | Line 151: | ||

the reporter gene, and on the other hand can activate the expression of B-A itself. In this way, | the reporter gene, and on the other hand can activate the expression of B-A itself. In this way, | ||

B-A can self-drive in a manner independent of the input signal for a period of time after the | B-A can self-drive in a manner independent of the input signal for a period of time after the | ||

| − | signal | + | signal of input, and the metabolic flow in this cycle can be transferred to the output circuit [2]. |

In particular, in our device, we want to use CRISPRa technology to achieve our goals. We will use | In particular, in our device, we want to use CRISPRa technology to achieve our goals. We will use | ||

| − | dCas9 as our binder | + | dCas9 as our binder and the SoxS as our activator which had been proven to be highly |

effective in bacteria [3]. In addition, when using an amplifier based on a positive feedback loop, | effective in bacteria [3]. In addition, when using an amplifier based on a positive feedback loop, | ||

we need to strictly limit its activation until the input signal is strong enough, which is | we need to strictly limit its activation until the input signal is strong enough, which is | ||

| Line 140: | Line 162: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/0b/T--NEU_China_A--fig4.jpg"> | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/0b/T--NEU_China_A--fig4.jpg"> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip"> | ||

| + | Figure 2. Schematic Design of the Synthetic amplifier. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

<div class="borderleft"> | <div class="borderleft"> | ||

<p>For some reasons, we have not been able to do experiment in this area, but we have established a | <p>For some reasons, we have not been able to do experiment in this area, but we have established a | ||

| Line 145: | Line 171: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <div class="light-blue-text"> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Leonard, N., Bishop, A. E., Polak, J. M., and Talbot, I. C. (1998) Expression of nitric oxide synthase in inflammatory bowel disease is not affected by corticosteroid treatment. J. Clin. Pathol. 51, 750−753.<br/> |

| − | [2] Smole,A., Lainsˇcek,D., Bezeljak,U., Horvat,S. and Jerala,R. (2017) A synthetic mammalian therapeutic gene circuit for sensing and suppressing inflammation. Mol. Ther., 25, 102–119. | + | [2] Smole,A., Lainsˇcek,D., Bezeljak,U., Horvat,S. and Jerala,R. (2017) A synthetic mammalian therapeutic gene circuit for sensing and suppressing inflammation. Mol. Ther., 25, 102–119.<br/> |

| − | [3] Chen Dong, Jason Fontana, Anika Patel, James M. Carothers and Jesse G. Zalatan. (2018) Synthetic CRISPR-Cas gene activators for transcriptional reprogramming in bacteria. Nat. Commun.</ | + | [3] Chen Dong, Jason Fontana, Anika Patel, James M. Carothers and Jesse G. Zalatan. (2018) Synthetic CRISPR-Cas gene activators for transcriptional reprogramming in bacteria. Nat. Commun.</p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 165: | Line 191: | ||

Interleukin-10 is a natural immunosuppressive cytokine that is normally released by regulatory T | Interleukin-10 is a natural immunosuppressive cytokine that is normally released by regulatory T | ||

cells and plays an important role in intestinal homeostasis [4]. In our engineered bacteria, we | cells and plays an important role in intestinal homeostasis [4]. In our engineered bacteria, we | ||

| − | + | aim to induce the release of interleukin-10 through the inflammatory signal nitric oxide to | |

| − | achieve drug release controllability. In particular, we have | + | achieve drug release controllability. In particular, we have fused the secreted protein YebF [5] |

| − | in E. coli with interleukin-10 to help our drugs be delivered extracellularly. This is more | + | in <i>E. coli</i> with interleukin-10 to help our drugs be delivered extracellularly. This is more |

convenient than using an ABC protein-mediated secretion system.</p> | convenient than using an ABC protein-mediated secretion system.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9e/T--NEU_China_A--fig5.jpg"> | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9e/T--NEU_China_A--fig5.jpg"> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip"> | ||

| + | Figure 3. The effect of our anti-inflammatory E. coli. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<div class="borderleft"> | <div class="borderleft"> | ||

| − | <p>During our HP event, we made conversations with specialists of IBD, | + | <p>During our HP event, we made conversations with specialists of IBD, During the conversation, we learned that |

the biologic TNF monoclonal antibody (eg. Adalimumab) is a more effective therapeutic output. | the biologic TNF monoclonal antibody (eg. Adalimumab) is a more effective therapeutic output. | ||

However, the cost of antibody drugs is expensive and it is difficult for ordinary people to afford. | However, the cost of antibody drugs is expensive and it is difficult for ordinary people to afford. | ||

| Line 180: | Line 210: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <div class="light-blue-text"> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Steidler, L. Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10. Science 289, 1352–1355 (2000).<br/> |

| − | [2] Gardlik R, Palffy R, Celec P (2012) Recombinant probiotic therapy in experimental colitis in mice. Folia Biol (Praha) 58(6):238–245 | + | [2] Gardlik R, Palffy R, Celec P (2012) Recombinant probiotic therapy in experimental colitis in mice. Folia Biol (Praha) 58(6):238–245<br/> |

| − | [3] Whelan, R. A. et al. A transgenic probiotic secreting a parasite immunomodulator for site-directed treatment of gut inflammation. Mol. Ther. 22, 1730–1740 (2014). | + | [3] Whelan, R. A. et al. A transgenic probiotic secreting a parasite immunomodulator for site-directed treatment of gut inflammation. Mol. Ther. 22, 1730–1740 (2014).<br/> |

| − | [4] Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature (2011) 474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208 | + | [4] Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature (2011) 474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208<br/> |

| − | [5] Zhang G, Brokx S, Weiner JH (2006) Extracellular accumulation of recombinant proteins fused to the carrier protein YebF in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 24:100–104 | + | [5] Zhang G, Brokx S, Weiner JH (2006) Extracellular accumulation of recombinant proteins fused to the carrier protein YebF in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 24:100–104<br/> |

| − | </ | + | </p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 204: | Line 234: | ||

It can convert the precursor glucosinolates in cruciferous plants into sulforaphane, a well-known | It can convert the precursor glucosinolates in cruciferous plants into sulforaphane, a well-known | ||

anticancer substance [4]. Sulforaphane is an activator of Nrf2, which induces Nrf2 activation and | anticancer substance [4]. Sulforaphane is an activator of Nrf2, which induces Nrf2 activation and | ||

| − | translocation into the nucleus, | + | translocation into the nucleus, and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) to promote |

transcriptional activation of the phase II metabolic enzyme gene [5]. As a result, sulforaphane, on | transcriptional activation of the phase II metabolic enzyme gene [5]. As a result, sulforaphane, on | ||

the one hand, can eliminate cancer cells by inducing phase II reaction; on the other hand, it can | the one hand, can eliminate cancer cells by inducing phase II reaction; on the other hand, it can | ||

| Line 212: | Line 242: | ||

hydrocarbon receptors, which activate the aromatic hydrocarbon receptors in intestinal epithelial | hydrocarbon receptors, which activate the aromatic hydrocarbon receptors in intestinal epithelial | ||

cells and immune cells to relieve inflammation, improve intestinal epithelial barrier tightness and | cells and immune cells to relieve inflammation, improve intestinal epithelial barrier tightness and | ||

| − | the ability to inhibit tumors[6, 7]. Therefore, we call on everyone to eat more vegetables!</p> | + | enhance the ability to inhibit tumors[6, 7]. Therefore, we call on everyone to eat more vegetables!</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fa/T--NEU_China_A--fig6.jpg"> | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fa/T--NEU_China_A--fig6.jpg"> | ||

| + | <p class="tooltip"> | ||

| + | <strong>Figure 4. Diet-mediated tumor chemoprevention and inflammation relief.</strong> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<div class="borderleft"> | <div class="borderleft"> | ||

<p>In our project, we chose the myrosinase from horseradish because it exhibits high catalytic activity | <p>In our project, we chose the myrosinase from horseradish because it exhibits high catalytic activity | ||

| Line 223: | Line 257: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<br /><br /> | <br /><br /> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <div class="light-blue-text"> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002; 347: 417–29.<br/> |

| − | [2] Kaser, A., Zeissig, S. & Blumberg, R. S. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 573–621 (2010). | + | [2] Kaser, A., Zeissig, S. & Blumberg, R. S. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 573–621 (2010).<br/> |

| − | [3] Ho CL, Tian HQ.et al. 2018 Engineered commensal microbes for diet-mediated colorectal-cancer chemoprevention. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2, pages27–37 | + | [3] Ho CL, Tian HQ.et al. 2018 Engineered commensal microbes for diet-mediated colorectal-cancer chemoprevention. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2, pages27–37<br/> |

| − | [4] Tortorella, S. M., Royce, S. G., Licciardi, P. V. & Karagiannis, T. C. Dietary sulforaphane in cancer chemoprevention: the role of epigenetic regulation and HDAC inhibition. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 1382–1424 (2015). | + | [4] Tortorella, S. M., Royce, S. G., Licciardi, P. V. & Karagiannis, T. C. Dietary sulforaphane in cancer chemoprevention: the role of epigenetic regulation and HDAC inhibition. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 1382–1424 (2015).<br/> |

| − | [5] Wakabayashi N, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW; Talalay P. Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: fate of cysteines of the Keapl sensor modified by inducers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2040一2045. | + | [5] Wakabayashi N, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW; Talalay P. Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: fate of cysteines of the Keapl sensor modified by inducers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2040一2045.<br/> |

| − | [6] Lamas B, Natividad J M, Sokol H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and intestinal immunity.[J]. Mucosal Immunology, 2018, 11(4). | + | [6] Lamas B, Natividad J M, Sokol H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and intestinal immunity.[J]. Mucosal Immunology, 2018, 11(4).<br/> |

| − | [7] Metidji A, Omenetti S, Crotta S, et al. The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity[J]. Immunity, 2018, 49(2):353-362.e5. | + | [7] Metidji A, Omenetti S, Crotta S, et al. The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity[J]. Immunity, 2018, 49(2):353-362.e5.<br/> |

| − | </ | + | </p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div><br /><br /> | </div><br /><br /> | ||

| Line 242: | Line 276: | ||

the environment and cause gene leakage when we use engineered bacteria to treat IBD. In our | the environment and cause gene leakage when we use engineered bacteria to treat IBD. In our | ||

project, we designed a cold shock kill switch based on the toxin-antitoxin system-mazEF- a natural | project, we designed a cold shock kill switch based on the toxin-antitoxin system-mazEF- a natural | ||

| − | toxin-antitoxin system found in E. coli. MazF is a stable toxin protein, and mazE is an unstable | + | toxin-antitoxin system found in <i>E. coli</i>. MazF is a stable toxin protein, and mazE is an unstable |

antitoxin protein [1]. When the bacteria are inhibited by environmental stress and the expression | antitoxin protein [1]. When the bacteria are inhibited by environmental stress and the expression | ||

of mazEF is inhibited, the unstable antitoxin protein is preferentially degraded, and the relative | of mazEF is inhibited, the unstable antitoxin protein is preferentially degraded, and the relative | ||

| Line 254: | Line 288: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b1/T--NEU_China_A--fig7.jpg"> | <img class="responsive-img" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b1/T--NEU_China_A--fig7.jpg"> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | <p class="tooltip"> |

| + | <strong>Figure 5. Schematic Design of the Kill Switch.</strong> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <div class="light-blue-text"> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>[1] Aizenman E, Engelberg-Kulka H, Glaser G, et al. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine 3′5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 1996, 93(12): 6059−6063.<br/> |

| − | [2] Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005, 33(3): 966−976. | + | [2] Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005, 33(3): 966−976.<br/> |

| − | [3] Amitai S, Yassin Y, Engelberg-Kulk H. MazF-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli: A point of no return. J Bacteriol, 2004, 186(24): 8295−8300. | + | [3] Amitai S, Yassin Y, Engelberg-Kulk H. MazF-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli: A point of no return. J Bacteriol, 2004, 186(24): 8295−8300.<br/> |

| − | [4] Stirling F, Bitzan L, O'Keefe S, et al. Rational Design of Evolutionarily Stable Microbial Kill Switches[J]. Molecular Cell, 2017, 68(4):686-697. | + | [4] Stirling F, Bitzan L, O'Keefe S, et al. Rational Design of Evolutionarily Stable Microbial Kill Switches[J]. Molecular Cell, 2017, 68(4):686-697.<br/> |

| − | [5] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018).</ | + | [5] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018).</p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 281: | Line 318: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| + | {{Template:NEU_China_A/footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:12, 18 October 2018

-

folder_openProject

-

placeLab

-

detailsParts

-

lightbulb_outlineHP

-

peopleTeam

Design

Design

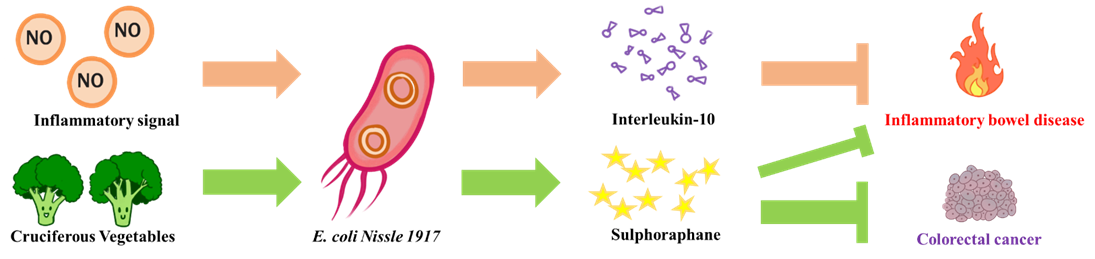

The goal of NEU_China_A is to design a biological system to alleviate intestinal inflammatory diseases and prevent potential colorectal cancer. We chose the human probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, as our chassis for constructing engineered probiotic. On the one hand, when the engineered bacteria senses an inflammatory signal in the intestine, it would release an anti-inflammatory compound (interleukin-10, IL-10) to reduce the intestinal inflammatory responses. On the other hand, engineered E. coli could secrete myrosinase to convert the cruciferous vegetables contained glucosinolate into sulforaphane that act as similar as IL-10 and prevent colorectal cancer induced by chronic inflammation.

The very first one coming to our minds was to choose a suitable chassis when we decided to use engineered bacteria to alleviate inflammatory bowel disease. Through literature review, we have found a bacteria that is clinically widely used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease - E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) [1], which was isolated by German fetus Alfred Nissle during the First World War from the feces of a German soldier who was insusceptible to infectious diarrhea [2]. Alfred Nissle put the bacteria cultured on the agar plate into gelatin capsules and seals them with paraffin to make the drug Mutaflor [3]. Subsequent studies have confirmed that EcN lacks virulence factors and has obvious probiotic properties, and is a safe and effective carrier for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease [1]. EcN has excellent biofilm formation ability, so it has better colonization ability than other probiotic carriers, and it can inhibit the colonization of pathogens [4]. In addition, EcN can inhibit intestinal pathogens by secreting microcin and inducing epithelial cells to secrete defensing-2 [5, 6]. Due to the excellent properties of EcN, in 2004, it was recommended by the German Society of Gastroenterology and Digestive Diseases (DGVS) as an alternative to the UC standard for the treatment of mesalamine [7]. However, there are also some negative reports that EcN is not completely safe [8]. Therefore, we hope to use the modified EcN strain SYNB1618 as our final chassis. SYNB1618 lacks colonization ability and is completely eliminated within 48 hours in the mouse model, so it is a safer chassis [9]. As a consequence of limited time and effort, in our experiments, we only used DH5α and BL21 strains to test the performance of our system. Nevertheless, we hope that our engineered bacteria will be filled in capsules and taken orally to treat IBD in the future.

[1] Schultz M. Clinical use of E. coli Nissle 1917 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2008, 14(7): 1012-1018.

[2] Nissle A. Die antagonistische Behandlung chronischer Darmstoerungen mit Colibakterien [The antagonistic therapy of chronic intestinal disturbances]. Med Klinik. 1918:29–30.

[3] Nissle A. Weiteres ueber die Grundlagen und Praxis der Mutaflorbehandlung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1925;44:1809–1813.

[4] Hancock V, Dahl M, Klemm P: Probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 outcompetes intestinal pathogens during biofilm formation. J Med Microbiol 2010; 59: 392–399.

[5] Sassonecorsi M, Nuccio S P, Liu H, et al. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut[J]. Nature, 2016, 540(7632):280-283.

[6] Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, et al. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–2407.

[7] Hoffmann CJ, Zeitz M, Bischoff SC, et al. [Diagnosis and therapy of ulcerative colitis: results of an evidence based consensus conference by the German society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the competence network on inflammatory bowel disease.] Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:979–983.

[8] Jacobi C A, Malfertheiner P. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor): New Insights into an Old Probiotic Bacterium[J]. Digestive Diseases, 2011, 29(6):600.

[9] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018).

2. Inflammatory sensor

Engineered bacteria could be an ideal way to treat IBD. First, we need an appropriate sensor to sense the inflammatory signal and initiate the release of the drug. After comparing the inflammatory sensors used in some iGEM teams, we selected the inflammatory sensor based on nitric oxide molecules used by ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team. Nitric oxide is a natural signaling molecule of inflammation, and the concentration of intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD is significantly increased [1]. It has been reported that the average concentration of nitric oxide in the rectum of normal people reaches 60 nM, while in patients with IBD it reaches 5.5 μM, nearly 100 times higher than that of the former [2]. Therefore, the nitric oxide molecule is an ideal input signal for engineered bacteria, allowing the engineered bacteria to function only at the target location, thereby avoiding inappropriate output.

There are some natural nitric oxide sensors in E. coli, in which the enhancer binding protein NorR is specific and can only react with nitric oxide and cannot interact with other nitrogen forms [3]. NorR binds to three conserved sites on the NorV promoter (PnorV) via the C-terminal HTH domain. When nitric oxide is absent, the N-terminal domain- GAF of NorR blocks the central domain-AAA+ to inhibit its binding to the transcription factor - σ 54, and thereby prevent transcription of the nitric oxide reductase - NorV. When nitric oxide binds to the GAF domain of NorR, it will release the AAA+ domain, allowing σ 54 to initiate transcription of NorV [4].

Figure 1. Engineered bacteria with inflammation sensor.

In our inflammation sensor, we used two parts which are NorR and PnorV. GFP and amilCP were selected as our reporter genes. Although the E. coli host has native NorR expression, increasing its expression facilitates the elimination of stoichiometric imbalances between NorR in the genome and PnorV on the foreign plasmid, avoiding interference with the host's release of nitric oxide [5]. We used the double expression plasmid pCDFDuet-1 to construct our sensor module. Placing NorR under the control of the first T7 promoter, we are able to regulate its expression by IPTG induction. We also replaced the second promoter with PnorV and added the reporter gene downstream which allows us to activate the expression of the reporter gene by adding nitric oxide. In addition, during our participation in the 5th CCiC, we communicated with the team of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. We learned that they detected colorectal cancer through the gene expression initiated by nitric oxide-inducible promoter PyeaR, when we were having trouble detecting the expression of the reporter gene GFP after using nitric oxide to drive PnorV. Meanwhile, we also tested the effect of PyeaR in response to nitric oxide.

[1] Rachmilewitz D, Stamler J S, Bachwich D, et al. Enhanced colonic nitric oxide generation and nitric oxide synthase activity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease[J]. Gut, 1995, 36(5): 718-723.

[2] Ljung T, Herulf M, Beijer E, et al. Rectal nitric oxide assessment in children with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Indicator of ileocaecal and colorectal affection[J]. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 2001, 36(10): 1073-1076.

[3] Tucker, N. P., D’Autreaux, B., Yousafzai, F. K., Fairhurst, S. A., Spiro, S., and Dixon, R. (2008) Analysis of the nitric oxide-sensing non-heme iron center in the NorR regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 908−918.

[4] Bush, M., Ghosh, T., Tucker, N., Zhang, X., and Dixon, R. (2011) Transcriptional regulation by the dedicated nitric oxide sensor, NorR: a route towards NO detoxification. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 289−293.

[5] Archer, E.J., Robinson, A.B. & Suel, G.M. Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS Synth. Biol. 1, 451–457 (2012).

3. Amplifier

Despite that, as an inflammatory signal, nitric oxide has good specificity and regionality. It is a reactive gas signal molecule with a short half-life [1], which decays sharply with increasing distance, suggesting that the input signal is very unstable. To overcome this drawback, we have introduced an amplifier in the sensor. The amplifier converts unstable gas signals into stable intracellular signals to gain sustained high-level output. The sustainability is very important because it also prevents signal attenuation in the immediate vicinity of the device due to anti-inflammatory drug delivery [2]. The amplifier is based on a positive feedback loop, and after the signal is input, the transcriptional activator B-A is generated, which includes a DNA binding domain and a transcriptional activation domain. On the one hand, B-A can activate the expression of the reporter gene, and on the other hand can activate the expression of B-A itself. In this way, B-A can self-drive in a manner independent of the input signal for a period of time after the signal of input, and the metabolic flow in this cycle can be transferred to the output circuit [2]. In particular, in our device, we want to use CRISPRa technology to achieve our goals. We will use dCas9 as our binder and the SoxS as our activator which had been proven to be highly effective in bacteria [3]. In addition, when using an amplifier based on a positive feedback loop, we need to strictly limit its activation until the input signal is strong enough, which is beneficial to suppress leakage of the device [2]. To this end, we introduce the concept of thresholds, which is to achieve competition between B-A and B by constitutively expressing dCas9 with a certain intensity. In this way, the amplifier can only be effectively activated when the input signal is strong enough.

Figure 2. Schematic Design of the Synthetic amplifier.

For some reasons, we have not been able to do experiment in this area, but we have established a mathematical model to predict the performance of the amplifier.

[1] Leonard, N., Bishop, A. E., Polak, J. M., and Talbot, I. C. (1998) Expression of nitric oxide synthase in inflammatory bowel disease is not affected by corticosteroid treatment. J. Clin. Pathol. 51, 750−753.

[2] Smole,A., Lainsˇcek,D., Bezeljak,U., Horvat,S. and Jerala,R. (2017) A synthetic mammalian therapeutic gene circuit for sensing and suppressing inflammation. Mol. Ther., 25, 102–119.

[3] Chen Dong, Jason Fontana, Anika Patel, James M. Carothers and Jesse G. Zalatan. (2018) Synthetic CRISPR-Cas gene activators for transcriptional reprogramming in bacteria. Nat. Commun.

When our anti-inflammatory device is activated by an inflammatory signal, it produces a therapeutic output. Although therapeutic output increases the risk of infection, to some extent, our chassis EcN compensates for this deficiency by inhibiting pathogens. When we consider what output should be used, the first consideration is the epidermal growth factor used by ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team. EGF can accelerate the repair of intestinal epithelial mucosa. However, we think it is not advisable, considering that it will exacerbate the risk of colorectal cancer in patients with IBD. In our review of the literature, we noticed that some researchers used engineered constitutive secretory immunosuppressants in animal models to alleviate IBD and achieved good results [1-3]. Interleukin-10 is a natural immunosuppressive cytokine that is normally released by regulatory T cells and plays an important role in intestinal homeostasis [4]. In our engineered bacteria, we aim to induce the release of interleukin-10 through the inflammatory signal nitric oxide to achieve drug release controllability. In particular, we have fused the secreted protein YebF [5] in E. coli with interleukin-10 to help our drugs be delivered extracellularly. This is more convenient than using an ABC protein-mediated secretion system.

Figure 3. The effect of our anti-inflammatory E. coli.

During our HP event, we made conversations with specialists of IBD, During the conversation, we learned that the biologic TNF monoclonal antibody (eg. Adalimumab) is a more effective therapeutic output. However, the cost of antibody drugs is expensive and it is difficult for ordinary people to afford. In the future, we will enable engineered bacteria to jointly release immunosuppressive agents and TNF monoclonal antibodies under controlled conditions to achieve better efficacy while reducing treatment costs.

[1] Steidler, L. Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10. Science 289, 1352–1355 (2000).

[2] Gardlik R, Palffy R, Celec P (2012) Recombinant probiotic therapy in experimental colitis in mice. Folia Biol (Praha) 58(6):238–245

[3] Whelan, R. A. et al. A transgenic probiotic secreting a parasite immunomodulator for site-directed treatment of gut inflammation. Mol. Ther. 22, 1730–1740 (2014).

[4] Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature (2011) 474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208

[5] Zhang G, Brokx S, Weiner JH (2006) Extracellular accumulation of recombinant proteins fused to the carrier protein YebF in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 24:100–104

5. Diet-mediated tumor chemoprevention and inflammation relief

Although the use of immunosuppressive agents can have a good effect, it also has certain side effects(eg. increasing the risk of lymphoma) [1]. In addition, we need to consider the high risk of colorectal cancer in patients with IBD in the design of the project [2]. Therefore, we hope to combine the cruciferous vegetable diet with the engineering bacteria that release myrosinase to chemically prevent tumors [3].

Myrosinase is present in cruciferous plants such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts and Chinese cabbage. It can convert the precursor glucosinolates in cruciferous plants into sulforaphane, a well-known anticancer substance [4]. Sulforaphane is an activator of Nrf2, which induces Nrf2 activation and translocation into the nucleus, and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) to promote transcriptional activation of the phase II metabolic enzyme gene [5]. As a result, sulforaphane, on the one hand, can eliminate cancer cells by inducing phase II reaction; on the other hand, it can alleviate inflammation by inducing antioxidant enzymes (such as HO-1 and SOD) to resist oxidative stress.

In addition, cruciferous vegetables are metabolized in the body to produce ligands for aromatic hydrocarbon receptors, which activate the aromatic hydrocarbon receptors in intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells to relieve inflammation, improve intestinal epithelial barrier tightness and enhance the ability to inhibit tumors[6, 7]. Therefore, we call on everyone to eat more vegetables!

Figure 4. Diet-mediated tumor chemoprevention and inflammation relief.

In our project, we chose the myrosinase from horseradish because it exhibits high catalytic activity at physiological temperature and pH [3]. We fused the myrosinase and the secreted protein Yebf and used a constitutive promoter to activate expression of the fusion protein. In this way, we can get enough myrosinase in the intestinal environment to make the cruciferous vegetable diet play an effective chemical prevention of tumors and relieve chronic inflammation.

[1] Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002; 347: 417–29.

[2] Kaser, A., Zeissig, S. & Blumberg, R. S. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 573–621 (2010).

[3] Ho CL, Tian HQ.et al. 2018 Engineered commensal microbes for diet-mediated colorectal-cancer chemoprevention. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2, pages27–37

[4] Tortorella, S. M., Royce, S. G., Licciardi, P. V. & Karagiannis, T. C. Dietary sulforaphane in cancer chemoprevention: the role of epigenetic regulation and HDAC inhibition. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 1382–1424 (2015).

[5] Wakabayashi N, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW; Talalay P. Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: fate of cysteines of the Keapl sensor modified by inducers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2040一2045.

[6] Lamas B, Natividad J M, Sokol H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and intestinal immunity.[J]. Mucosal Immunology, 2018, 11(4).

[7] Metidji A, Omenetti S, Crotta S, et al. The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity[J]. Immunity, 2018, 49(2):353-362.e5.

6. Biocontainment

It is necessary for us to do bio-protection work to avoid the release of engineered bacteria into the environment and cause gene leakage when we use engineered bacteria to treat IBD. In our project, we designed a cold shock kill switch based on the toxin-antitoxin system-mazEF- a natural toxin-antitoxin system found in E. coli. MazF is a stable toxin protein, and mazE is an unstable antitoxin protein [1]. When the bacteria are inhibited by environmental stress and the expression of mazEF is inhibited, the unstable antitoxin protein is preferentially degraded, and the relative content of the stable toxin protein increases to a certain extent, which will lead to the death of bacterial [2, 3]. The mRNA mediated by the cold-acting promoter CspA can only be efficiently translated at a low temperature of, for example, 16 ° C [4], so we use it to activate the expression of mazF at low temperatures. In this way, when the engineered bacteria leaves the intestine and enters the environment, it will be killed by our cold shock kill switch. In the future, we hope to integrate the genes contained in our system into the genome of engineered bacteria to provide genetic stability [5] and to avoid the use of plasmids with antibiotic genes.

Figure 5. Schematic Design of the Kill Switch.

[1] Aizenman E, Engelberg-Kulka H, Glaser G, et al. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine 3′5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 1996, 93(12): 6059−6063.

[2] Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005, 33(3): 966−976.

[3] Amitai S, Yassin Y, Engelberg-Kulk H. MazF-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli: A point of no return. J Bacteriol, 2004, 186(24): 8295−8300.

[4] Stirling F, Bitzan L, O'Keefe S, et al. Rational Design of Evolutionarily Stable Microbial Kill Switches[J]. Molecular Cell, 2017, 68(4):686-697.

[5] Isabella, V. et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857–864 (2018).