-

folder_openProject

-

placeLab

-

detailsParts

-

lightbulb_outlineHP

-

peopleTeam

Overview

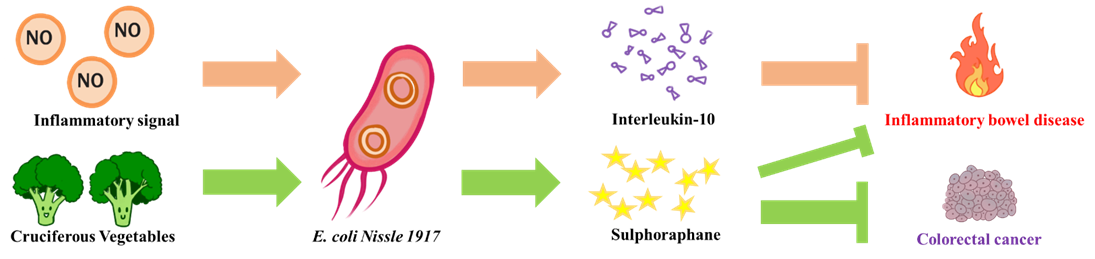

The goal of NEU_China_A is to design a biological system to alleviate intestinal inflammatory diseases and prevent potential colorectal cancer. We chose the human probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, as our chassis for constructing engineered probiotic. On the one hand, when the engineered bacteria senses an inflammatory signal in the intestine, it would release an anti-inflammatory compound (interleukin-10, IL-10) to reduce the intestinal inflammatory responses. On the other hand, engineered E. coli could secrete myrosinase to convert the cruciferous vegetables contained glucosinolate into sulforaphane that act as similar as IL-10 and prevent colorectal cancer induced by chronic inflammation.

For details about our project background and introduction, please click toDescription

For details of whole project design, please click toDesign

As a therapeutic project, we knew the difficulties for verifying the entire system in less than one year. We split the entire system into three core parts and verify them separately: the nitric oxide sensor (nitric oxide, NO, is a biomarker of intestinal inflammation), protein transport and production and the “kill switch”. In addition, we tested them in DH5α and BL21 E.coli competent cells. We believed that the success of these core parts will ultimately ensure the entire system functioning in IBD patients.

In order to detect the NO specifically and accurately, we constructed pCDFDuet-1 plasmid as our expression vector, which contains the NO binding protein for expressing reporter gene. (Figure 1). Briefly, we integrated NO-binding protein, NorR, into this plasmid for activating the amilCP reporter gene expression via binding to PnorV promoter. To testify the validity of NO sensor, we used T7 promoter and lacO protein for boosting the NorR expression under the IPTG induction.

Figure 1. Diagram for NO sensor system in pCDFDuet-1 plasmid. T7 promoter, the gene downstream of this promoter will be transcribed when there is T7 RNA polymerase. lacO, the sequence represses the nearby promoter when there is no inducer (e.g. IPTG). RBS, ribosome binding site. NorR, NO binding protein. PnorV, a promoter which is sensitive to NO. amilCP, blue chromoprotein. T7 terminator, a terminator from T7 phage.

According to the previous work, ShanghaiTechChina_B 2016 team demonstrated 100μM Sodium Nitroprusside Dihydrate (SNP) aqueous solution could continuously release NO and its final concentration is stab at about 5.5μM, which as same as the NO amount in IBD patients and 100 times higher than healthy individuals [1]. According to their work, we could simulate the IBD patients’ NO signal in vitro. In the subsequent test of the NO sensor, the final concentration of the SNP aqueous solution was maintained at 100 μM.

We transformed the constructed plasmid with NO sensor into DH5α, cultured at 37 ℃ overnight, and then diluted to OD600 = 0.2. Culturing bacteria at 37 ℃ for 1.5 hours, the appropriate concentration of inducer IPTG and SNP aqueous solution were added. After 6 hours of culturing, 1 mL of the bacterial solution was centrifuged at 8000 r.p.m for 1 min (Figure 2). It can be seen that the NO released by the SNP aqueous solution can effectively activate the expression of the reporter gene. Surprisingly, the blue chromoprotein in group 1mM IPTG without SNP was also be activated with undetermined mechanisms. We speculated that it may be caused by leakage expression of promoter PnorV when the NorR is overexpressed. Due to this reason, we would use a weak promoter to express NorR in further engineered bacteria.

Figure 2. Pellets of bacteria transformed with constructed NO sensor plasmid after 6hr induction at 37 ℃. From left to right: control, 0.5mM IPTG without SNP, 1mM IPTG without SNP, 0.5mM IPTG with 100μM SNP, 1mM IPTG with 100μM SNP.

Besides, during our participation in the 5th CCiC (Conference of China iGEMer Community), we communicated with the iGEM team of SJTU-BioX-Shanghai and learnt that they detected colorectal cancer through the nitric oxide inducible promoter PyeaR, they used NO as their input signal. And at that time which happened to be difficult for us to detect the expression of the reporter gene GFP after using nitric oxide to drive PnorV. So, we also tested the effect of PyeaR (BBa_K381001) in the Distribution Kit (Figure 3).

We transformed the plasmid containing BBa_K381001 into DH5α, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight and then diluted to OD600 = 0.4. Then we took half of bacteria as control and the rest was added SNP aqueous solution, and induced at 37 ℃ for 6 h. Then the fluorescence intensity of cells were observed under microplate reader and fluorescence inverted microscope (Figure 4). The histogram of GFP fluorescent density and microscope images indicated that PyeaR could effectively activated by NO and there was almost no leakage expression. In the future, we will use PyeaR promoter based plasmid as the NO sensor.

Figure 4. The response to NO of BBa_K381001. A, Histogram of GFP fluorescence: LB control, without SNP, with 100μM SNP. B, GFP fluorescence images from top to bottom: without SNP, with 100μM SNP.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the validity of PyeaR based NO sensor in E. coli of responding to chemically produced nitric oxide in vitro. Since the PyeaR promoter is presence in wild type E. coli. strain, it should be functioning in our engineered probiotic E. coli strain. Moreover, this engineered probiotic might detect the inflammatory signal, NO, in host intestinal tract.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817000

BBa_K381001

At the beginning of the experiment, we directly constructed the plasmids of YebF-IL10 and YebF-myrosinase, but the effect of extracellular detection was not good. During the participation in CCiC, iGEMer suggested that we should firstly try to test the performance of the secretory tag YebF, so we constructed the plasmid YebF-GFP shown in Figure 5A. To express IL10 and myrosinase, we constructed plasmids IL10-Flag and myrosinase-His as shown in Figure 5B and Figure 5C.

Figure 5. Production module construction. A, the construction of our YebF-GFP using strong promoter. J23110, a strong constitutive promoter. YebF-GFP, GFP with secretion tag. B, the construction of IL10 production module. IL10-Flag, human interleukin 10 with Flag tag. C, the construction of myrosinase production module. Myrosinase-his, our transferase with His tag.

According to previous works, the secretory tag YebF has been demonstrated as the functioning part in E.coli [2],thus, we chose this tag for further experiment.

When testing the validity of the secretory tag YebF, we transformed the constructed YebF-GFP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37 ℃. The bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 3,000 r.p.m for 5 min and the supernatant was taken for fluorescence detection. The result is shown in the Figure 6. From our data, the YebF based secretory part worked efficiently.

Figure 6. The fluorescence density of overnight bacterial suspension

Next, we transformed the human IL10-Flag plasmid (Fig 5B) into BL21, incubated at 37 ℃ overnight and then diluted to OD600 = 0.2. After 2 h of growth at 37 ℃, IPTG was added to induce IL10 expression at 30 ℃ for 16 h. Then, the bacterial solution was lysed and the expressed IL10 was detected by Western Blot (Figure 7). From this result, IL10 was successfully expressed in our constructed plasmid. As a widely validated and used anti-inflammatory interleukin, IL10 has been identified with critical functions in immunosuppression in human [3].

Figure 7. Western blot analyses using a flag antibody on bacterial lysate to detect IL10. Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.5mM IPTG.

Next, we transformed the plasmid of myrosinase-His (Fig 5C) into BL21, and cultured at 37 ℃ overnight and diluted to OD = 0.2. After growth for 2 h at 37 ℃, different concentrations of IPTG were added to induce at 16 ℃ for 16 h. Subsequently, bacterial cell lysate was obtained and the expression of myrosinase was detected by SDS-PAGE. (Figure 8). The sequence of the myrosinase enzyme was optimized based on the K12 strain and the position of the strip is correct, so myrosinase was successfully expressed. The myrosinase can convert cruciferous vegetables contained glucosinolates into sulforaphane which has well-known anti-cancer activity. A previous work demonstrated the activity of myrosinase expressed by E. coli Nissle 1917 in vivo and in vitro [4], the expressed myrosinase in our constructed plasmid should with broad applications in vivo.For more details about this transferase related information, please see our project design.

Figure 8. SDS-PAGE analyses of bacterial lysate to detect myrosinase. Lane 1: Negative control (cell lysate without IPTG induction); Lane 2: 0.25mM IPTG; Lane3: 0.5mM IPTG, Lane4: 0.75mM IPTG induction for 16h at 16℃.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817013

BBa_K2817002

BBa_K2817004

When we use engineered bacteria to alleviate IBD in vivo, the growth of bacteria must be tightly regulated. Therefore, we designed a cold shock kill switch that based on the toxin-antitoxin system mazEF. The rational of this kill switch is relying on the mechanism that when E. coli is under stress, the maz-E well degrade faster than maz-F, so the relatively more maz-F will exert its toxicity. The cold shock promoter PcspA was linked with maz-F, so when the temperature is low, the maz-F will express while the maz-E stop expressing. Thus, we could kill our engineered E. coli when it escapes from human body. We inserted the reporter gene amilCP into the pColdI plasmid to characterize the performance of the cold shock promoter PcspA (Figure 9A). Then we inserted maz-F into the pColdI plasmid to build our kill switch (Figure 9B).

Figure 9. Kill switch module construction. A, the construction of PcspA-amilCP plasmid. PcspA, the cold shock promoter. B, the construction of PcspA-mazF plasmid. mazF, the toxin gene from E. coli.

We transformed the PcspA-amilCP plasmid into DH5α and cultured overnight at 37 ℃. The overnight culture was diluted to = 0.2 and then grow for 2 h at 37 ℃. It was then induced for 6 hours at 16 ° C or 37 ℃ under different concentrations of IPTG conditions (Figure 10). From Figure 10, the reporter gene was efficiently expressed at low temperature, which indicated that the effective expression of the toxin gene mazF and the blocking expression of the anti-toxin gene mazE at low temperature can kill our engineered bacteria in time. Although the cold shock promoter PcspA can prevent the most of the leakage expression at 37 ℃, the weak leakage expression of mazF may still cause the functioning engineered probiotics being killed in human. Therefore, the introduction of the anti-toxin protein mazE is necessary to effectively antagonize the potential leakage expression of the cold shock promoter PcspA.

Figure 10. Pellets of bacteria transformed with constructed PcspA-amilCP plasmid after induction of 6h. From left to right: 37℃ without IPTG, 37℃ with 0.5mM IPTG, 37℃ with 1mM IPTG, 16℃ without IPTG, 16℃ with 0.5mM IPTG, 16℃ with 1mM IPTG.

Moreover, in order to test the efficiency of mazF. We transformed the constructed PcspA-mazF plasmid into BL21, added 1 mM IPTG to the plate, and cultured at 16℃ for 16 h (Figure 11A). We then cultured BL21 transformed with the PcspA-mazF plasmid overnight at 16℃. After diluting to OD600=0.02 on the next day, the cells were cultured at 16℃, and the OD value was measured every hour for 9 hours (Figure 11B). From Figure 11, the kill switch worked efficiently at low temperatures and indicated that mazF enable to cause cell death even at low expression level.

Figure 11. The effect of our killer gene under 16℃. A, the plate of BL21 with and without killer gene under induction. B, C The effect of mazF and Lysis on the growth of Escherichia coli at different temperature (C,16℃; D,37℃) or in different plasmids.

Parts for this section:

BBa_K2817012

BBa_K2817006

Finally, we are convinced the integration of these successful module will guarantee the effective work of our engineered system in E. coli under realistic conditions.

Reference

BBa_K2817012

BBa_K2817006

BBa_K2817012

BBa_K2817012