Kristinazu (Talk | contribs) |

Kristinazu (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/42/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig1_Ribosomes.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/42/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig1_Ribosomes.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 1 </strong> Principle of ribosome attachment to the liposome membrane. The ribosome exit tunnel is localized near the membrane, resulting in transmembrane domains of newly synthesized peptides interacting with the membrane, reducing aggregation</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 288: | Line 288: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fc/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_Ribosomes.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fc/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_Ribosomes.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 2 </strong> Scheme of the genome modification process: | |

<ol> | <ol> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

| Line 302: | Line 302: | ||

4. pTargetF is cured and the process can be repeated with a new target. | 4. pTargetF is cured and the process can be repeated with a new target. | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | </ol> | + | </ol></p> |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| Line 314: | Line 314: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a9/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig3_Ribosomes.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a9/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig3_Ribosomes.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong> Fig.3 </strong> Example of a constructed donor sequence. The sequence of the selected tag is present in primer used for the PCR of the homology arm that encompasses the target subunit. As a result, the tag sequence is fused to the ribosomal subunit gene.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 321: | Line 321: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d5/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig4_Ribosomes.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d5/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig4_Ribosomes.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong> Fig. 4 </strong> PCR of homology arms, and antibiotic resistance genes</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 327: | Line 327: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/86/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig5_Ribosomes.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/86/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig5_Ribosomes.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong> Fig. 5 </strong> Constructed donor DNA sequences. The L29 donor DNA was not further revisited due to time constraints</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 415: | Line 415: | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/ca/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_2.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/ca/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_2.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 2 </strong> Electrophoresis gel of PCR products: 6 - Sw2, 7 - Sw3, 8 - Sw6, 9 - Sw7, 10 - Sw9, 11 - Sw11.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| Line 422: | Line 422: | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d8/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_3.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d8/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_3.png"/> | ||

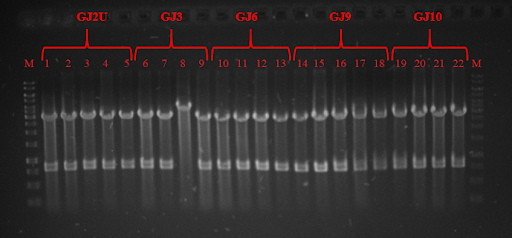

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 3 </strong> Restriction analysis of GJ<sub>x</sub> constructs</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a4/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_4.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a4/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_4.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 4 </strong> Colony PCR of RNA thermometers in pSB1C3 plasmid.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/46/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_5.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/46/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_5.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 5 </strong> expression at 24 ˚C. On the right you can see GFP expression without RNA thermometer.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p> <div class="image-container"> | <p> <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/dd/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_6.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/dd/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_6.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 6 </strong> GFP expression at 30 ˚C. On the right you can see GFP expression without RNA thermometer.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 441: | Line 441: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/78/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_7.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/78/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--THERMO_fig_7.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 7 </strong> GFP expression in 37 ˚C. On the right you can see GFP expression without RNA thermometer.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 453: | Line 453: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/af/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig8_NEW_thermoswitches.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/af/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig8_NEW_thermoswitches.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 8</strong> Associational scheme of thermoswitches’ action in the SynDrop system. Not locking the concomitant translation of our target protein and BamA results in target protein aggregation due to insufficient membrane insertion and assembling potential of BamA.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 459: | Line 459: | ||

<div class="image-container"> | <div class="image-container"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8b/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig9_NEW_thermoswitches.png"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8b/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig9_NEW_thermoswitches.png"/> | ||

| − | + | <p><strong>Fig. 9</strong> Associational scheme of thermoswitches’ action in the SynDrop system. Locking up translation gives time for proper folding and insertion of BamA and prevents undesirable aggregation of target membrane proteins.</p> | |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 580: | Line 580: | ||

<p>scFv consists of a minimal functional antigen-binding domain of an antibody (~30 kDa) (Fig. 1) , in which the heavy variable chain (VH) and light variable chain (VL) are connected by Ser and Gly rich flexible linker. [1] In most cases scFv is expressed in bacteria, where it is produced in cytoplasm, a reducing environment, in which disulfide bonds are not able to form and protein is quickly degraded or aggregated. Although poor solubility and affinity limit scFvs’ applications, their stability can be improved by merging with other proteins. [2] When expressed in cell free system, scFv should form disulfide bonds with the help of additional molecules. Merging to a membrane protein would provide additional stability and would display scFv on liposome membrane, where its activity could be detected. These improved qualities make ScFv recombinant proteins a perfect tool to evaluate, if SynDrop system acts in an anticipated manner. Of all possible scFvs we decided to use scFv-anti vaginolysin, which binds and neutralizes toxin vaginolysin (VLY). Its main advantage is rapid (< 1 h) and cheap detection of activity by inhibition of erythrocyte lysis (Fig. 2). Looking into future applications, scFvs are also attractive targets of molecular evolution, because one round of evolution would last less than one day thus generating a and wide range of different scFv mutants. Those displaying the highest affinity for antigens could be selected and used as drugs or drug carriers. </p> | <p>scFv consists of a minimal functional antigen-binding domain of an antibody (~30 kDa) (Fig. 1) , in which the heavy variable chain (VH) and light variable chain (VL) are connected by Ser and Gly rich flexible linker. [1] In most cases scFv is expressed in bacteria, where it is produced in cytoplasm, a reducing environment, in which disulfide bonds are not able to form and protein is quickly degraded or aggregated. Although poor solubility and affinity limit scFvs’ applications, their stability can be improved by merging with other proteins. [2] When expressed in cell free system, scFv should form disulfide bonds with the help of additional molecules. Merging to a membrane protein would provide additional stability and would display scFv on liposome membrane, where its activity could be detected. These improved qualities make ScFv recombinant proteins a perfect tool to evaluate, if SynDrop system acts in an anticipated manner. Of all possible scFvs we decided to use scFv-anti vaginolysin, which binds and neutralizes toxin vaginolysin (VLY). Its main advantage is rapid (< 1 h) and cheap detection of activity by inhibition of erythrocyte lysis (Fig. 2). Looking into future applications, scFvs are also attractive targets of molecular evolution, because one round of evolution would last less than one day thus generating a and wide range of different scFv mutants. Those displaying the highest affinity for antigens could be selected and used as drugs or drug carriers. </p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/99/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig1_Surface-scFv.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/99/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig1_Surface-scFv.png" | ||

| − | <p><strong>Fig. 1 </strong>Simplified structure of scFv Antibody</p> | + | <p><strong> Fig. 1 </strong>Simplified structure of scFv Antibody</p> |

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/97/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_NEW_real_Surface_scFV.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/97/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_NEW_real_Surface_scFV.png" | ||

| − | <p><strong>Fig. 2 </strong>Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.</p> | + | <p><strong> Fig. 2 </strong>Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.</p> |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

<h1>Results</h1> | <h1>Results</h1> | ||

| Line 588: | Line 588: | ||

<p>scFv constructs were created <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2622004"> BBa_K2622004. and checked by <a href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:Vilnius-Lithuania/Protocols"> colony PCR and DNA sequencing. scFv synthesis was performed in a cell free system. Validation of protein expression was done by running a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), see (Fig. 3)</p> | <p>scFv constructs were created <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2622004"> BBa_K2622004. and checked by <a href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:Vilnius-Lithuania/Protocols"> colony PCR and DNA sequencing. scFv synthesis was performed in a cell free system. Validation of protein expression was done by running a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), see (Fig. 3)</p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/83/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig2_Surface-scFv.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/83/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig2_Surface-scFv.png" | ||

| − | <p><strong>Fig. 3 </strong> SDS-PAGE of scFv. GFP is used as positive control, C- chaperone DnaK.</p> | + | <p><strong> Fig. 3 </strong> SDS-PAGE of scFv. GFP is used as positive control, C- chaperone DnaK.</p> |

<p>Red arrows in the photo indicate scFv anti-vaginolysin (~27 kDa). As successful synthesis was confirmed, the next step was to check if protein folded correctly and was able to bind its antigen - vaginolysin. We examined this by erythrocyte-lysis test, which was performed by comparing erythrocytes incubated with VLY (erythrocytes burst open) and erythrocytes incubated with VLY that was previously incubated with scFv anti-vaginolysin (less or no erythrocyte lysis). Results revealed that scFv binded to vaginolysin and inhibited cell lysis. Graph in (Fig. 4) demonstrates that scFv indeed attenuated the lysis of erythrocytes. These result prove scFv activity in IVTT system.</p> | <p>Red arrows in the photo indicate scFv anti-vaginolysin (~27 kDa). As successful synthesis was confirmed, the next step was to check if protein folded correctly and was able to bind its antigen - vaginolysin. We examined this by erythrocyte-lysis test, which was performed by comparing erythrocytes incubated with VLY (erythrocytes burst open) and erythrocytes incubated with VLY that was previously incubated with scFv anti-vaginolysin (less or no erythrocyte lysis). Results revealed that scFv binded to vaginolysin and inhibited cell lysis. Graph in (Fig. 4) demonstrates that scFv indeed attenuated the lysis of erythrocytes. These result prove scFv activity in IVTT system.</p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7b/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig3_Surface-scFv.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7b/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig3_Surface-scFv.png" | ||

| − | <p><strong>Fig. 4 </strong> Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different +/-scFv dilutions.</p> | + | <p><strong> Fig. 4 </strong> Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different +/-scFv dilutions.</p> |

<p>We then went one step further and constructed MstX-scFv_antiVLY <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2622038"> BBa_2622038, fusion protein, aiming to increase the stability of scFv having in mind future applications and experiments of exposing it on liposome surface. Fusion protein was expressed in E.coli cells; yellow to red arrows in (Fig. 5A) indicate MstX-scFv expression after induction with IPTG.</p> | <p>We then went one step further and constructed MstX-scFv_antiVLY <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2622038"> BBa_2622038, fusion protein, aiming to increase the stability of scFv having in mind future applications and experiments of exposing it on liposome surface. Fusion protein was expressed in E.coli cells; yellow to red arrows in (Fig. 5A) indicate MstX-scFv expression after induction with IPTG.</p> | ||

<p>Finally, we expressed the protein in a cell free system (Fig. 5B) along with scFv in order to compare how well scFv accomplishes its function alone or binded to other protein. In this case MstX-scFv_antiVLY fusion did not show superior activity than scFv_antiVLY alone (Fig. 6). These results also reveal that scFv_antiVLY is very sensitive and loses its activity with time. Ist and IInd attempts were separated by 1-2 hours. This amount of time is enough to measure decreasing activity. This must be taken into account when performing future experiments.</p> | <p>Finally, we expressed the protein in a cell free system (Fig. 5B) along with scFv in order to compare how well scFv accomplishes its function alone or binded to other protein. In this case MstX-scFv_antiVLY fusion did not show superior activity than scFv_antiVLY alone (Fig. 6). These results also reveal that scFv_antiVLY is very sensitive and loses its activity with time. Ist and IInd attempts were separated by 1-2 hours. This amount of time is enough to measure decreasing activity. This must be taken into account when performing future experiments.</p> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig_4._5._Surface_scFv.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig_4._5._Surface_scFv.png" | ||

| − | <p><strong>Fig. 5 </strong>A- MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in Escherichia coli. B- scFv_antiVLY and MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in cell-free system.</p> | + | <p><strong> Fig. 5 </strong>A- MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in Escherichia coli. B- scFv_antiVLY and MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in cell-free system.</p> |

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/0c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig6_Surface-scFv.png" | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/0c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--_Fig6_Surface-scFv.png" | ||

| − | <p>< | + | <p><strong>Fig 6. Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different scFv/MstX-scFv dilutions.</p> |

<h1>Conclusions</h1> | <h1>Conclusions</h1> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

Revision as of 01:17, 18 October 2018

Design and Results

Results

Cell-free, synthetic biology systems open new horizons in engineering biomolecular systems which feature complex, cell-like behaviors in the absence of living entities. Having no superior genetic control, user-controllable mechanisms to regulate gene expression are necessary to successfully operate these systems. We have created a small collection of synthetic RNA thermometers that enable temperature-dependent translation of membrane proteins, work well in cells and display great potential to be transferred to any in vitro protein synthesis system.

Fig. 1 Simplified structure of scFv Antibody

Fig. 1 Simplified structure of scFv Antibody

Fig. 2 Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.

Fig. 2 Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.

Fig. 3 SDS-PAGE of scFv. GFP is used as positive control, C- chaperone DnaK.

Fig. 3 SDS-PAGE of scFv. GFP is used as positive control, C- chaperone DnaK.

Fig. 4 Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different +/-scFv dilutions.

Fig. 4 Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different +/-scFv dilutions.

Fig. 5 A- MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in Escherichia coli. B- scFv_antiVLY and MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in cell-free system.

Fig. 5 A- MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in Escherichia coli. B- scFv_antiVLY and MstX-scFv_antiVLY expression in cell-free system.

Fig 6. Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different scFv/MstX-scFv dilutions.

Fig 6. Percentage of erythrocyte lysis at different scFv/MstX-scFv dilutions.