Justas2010 (Talk | contribs) |

Justas2010 (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 374: | Line 374: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

| − | + | <h1>Background</h1> | |

| − | + | <p> | |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | <P>Proteins that belong to a small group referred to as nonconstitutive membrane proteins can independently integrate into the membrane from the aqueous phase without the help of other proteins. This is because they possess a stable soluble form, that can bind to membranes and then insert and refold into another stable form.[1] However, most of the membrane proteins do not have a stable soluble form and rapidly aggregate when synthesized in the cytoplasm. That is why living organisms require additional machinery which facilitates MP insertion into membranes and catalyzes their folding.</P> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <h2>Structure of BAM complex | |

| − | + | </h2> | |

| − | + | <p>Assembly of the β-barrel bearing integral membrane proteins (MPs) into the target membrane is catalyzed by the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex. It contains five subunits, BamA–E.[2] BamA is composed of a 16-strand β-barrel integral membrane part and a periplasmic domain, which consists of five globular subdomains called POTRA motifs that are essential for complex formation and interaction with a substrate β-barrel proteins.[3] BamB-E are lipoproteins, each attaching to the inner leaflet of the OM via an N-terminal lipid moiety and playing an important role in promoting the folding of OMP.[4] (Fig.1) | |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | <div class="image-container"> | |

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/1/1c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig1_BAM_compl.png"/> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Fig. 1</strong> Structure of BAM complex</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Outer membrane protein (OMP) insertion into membrane in bacteria cells | ||

| + | </h2> | ||

| + | <div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3a/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_BAM_compl.png"/> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Fig. 2</strong> 5 steps scheme of OMP insertion into OM.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Generally MPs are integrated during translation with the assistance of the Sec Translocon. However, as there is no protein translation within the periplasm, OMPs require an alternative integration mechanism. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>In the beginning, OMPs are synthesized in the cytoplasm with N-terminal signal sequence that directs them to the Sec translocon, which transfers OMPs through the inner membrane into periplasm.[5] (Fig.2, step 1) | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>Integral membrane proteins forming β-barrel structures are prone to aggregate in aqueous environments. Therefore, after they transit a Sec channel, chaperones are required to bind OMPs to transfer them through the periplasmic compartment, while keeping them in an unfolded state to prevent aggregation.(Fig.2, step 2) The periplasmic chaperone, SurA has been shown to transfer most of the OMPs to the OM.[6] It has been shown that SurA directly participates in Bam-mediated OMP assembly by associating with BamA POTRA domain.[7] (Fig.2, step 3)</p> | ||

| + | <p>Final folding takes place in BAM complex. However, the mechanism how BAM complex catalyzes the insertion of β-barrel proteins into the OM still remains not fully understood. Structure analysis implies that the cavity seems to be too small to accomodate a fully folded OMP substrate, even though it is large enough to house couple of substrate β-hairpins.[2] (Fig.2, step 4)Based on the structure, it has been suggested that the rotation of the ring-like structure by POTRA domains and lipoproteins leads to the opening of a junction between the first and last β-strands of the BamA β-barrel (lateral gate) which promotes the insertion of OMPs into the lipid bilayer.[8] (Fig. 2, step 5) | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <h2>Our approach</h2> | ||

| + | <p>In order to reconstitute the fully working Bam complex we relied on the mechanisms elucidated before. SurA is a periplasmic chaperone which binds to unfolded β-barrel proteins and retains them in unfolded state, thus preventing aggregation. BamB or BamD lipoproteins can bind BamA-SurA, direct the complex to the membrane, and catalyze BamA insertion as well as correct folding in the membrane. [9] (Fig. 3, step 1) Knowing that in bacteria most of the Bam lipoproteins are found in BAM complex and full five proteins complex can be purified with one tag without any cross-links, we expected high complex association constants among the components (Fig.3, step 2) and hypothesized that BAM complex could be assembled in vitro simply by encapsulating BamA-SurA associatives and Bam lipoproteins.</p> | ||

| + | <div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3a/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig2_BAM_compl.png"/> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Fig. 3</strong> Bam lipoproteins assemble BamA in vitro</p> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <h1>Results</h1> | ||

| + | <h2>Plasmid construction</h2>> | ||

| + | <p>To purify the components of BAM complex we have constructed 6 plasmids:</p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li>pET28b-BamA</li> | ||

| + | <li>pET22b-BamA</li> | ||

| + | <li>pET22b-BamB</li> | ||

| + | <li>pCDFDuet-BamC-BamD</li> | ||

| + | <li>pET22b-BamE</li> | ||

| + | <Li>pET28b-SurA(more details in protocols)</Li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

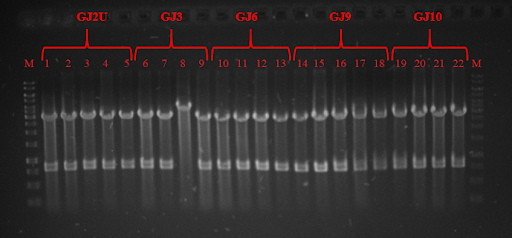

| + | which encode products of BamA-HisN6, BamA, BamB-HisC6, BamC, BamD, BamE-HisC8, SurA-HisN6. (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/30/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig3_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/5/54/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig4.1_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3d/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig4.2_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2e/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig5_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/85/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig6_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2c/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig7_BAM_compl.png"/> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Fig. 4</strong> Maps of constructed plasmids</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2e/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig5_BAM_compl.png"/><div class="image-container"> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Fig. 5</strong> PCR products of genes of BAM complex 1,18 – GeneRuler 1 kb DNA ladder; 4,5 – SurA (1250bp); 6,7 - BamE (390bp); 8,9 – BamB (1201bp); 10, 11 – BamC (1056bp); 12, 13 – BamD(756bp); 14,16 – BamA (2455bp)</p> | ||

| + | <h2> | ||

| + | Protein purification | ||

| + | </h2> | ||

| + | <p>We relied on three different strategies to purify the separate BAM complex components: </p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>For our experiments we needed an unfolded BamA. Therefore, we overexpressed BamA , which we isolated in the form of inclusion bodies and then dissolved in 8M urea without any further purification steps.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/85/T--Vilnius-Lithuania--Fig6_BAM_compl.png | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 6</strong> BamA after purification | ||

| + | 1 – BamA, 2 – BamA-HisN6, L – PageRuler Unstained Broad Range Protein Ladder | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <Li>Bam B-D lipoproteins were expressed with the pelB signal sequence, leading them to be exported to the periplasm where lipidation takes place. We then isolated the proteins from the membrane fraction, which we solubilised with specific detergents before purification using Ni-NTA (Fig.7 and Fig.9) and gelfiltration (size-exclusion) (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9) columns. BamCDE were purified as a single subcomplex via one octahistidine tag on BamE.</Li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <h3>After purification with Ni-NTA column:</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 7 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 7</strong> BamB after Ni-NTA column purification Lane L – PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, Lane 1 – Sample loaded on Ni-NTA Column, | ||

| + | Lanes 2-3 – Flow through fractions, Lanes 4-5 – washing fractions, Lanes 6-9 – Elution fractions | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3> After gelfiltration:</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 8 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 8</strong>BamB fractions after gelfiltration | ||

| + | Lane L – PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, Lanes 1-14 Elution fractions | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3> After gelfiltration:</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 9 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 9</strong> BamCDE after Ni-NTA column purification Lane L – PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, Lane 1,2 - Flow through fractions, Lanes 3-4 – washing fractions, Lanes 5-7 – Elution fractions | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>After gelfiltration:</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 10 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 10</strong> BamCDE fractions after gelfiltration | ||

| + | Lane 1 – PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, 2-15 elution fractions | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | While SurA is a periplasmic protein, we had no issues overexpressing it in the cytoplasm for increased yield. We used a hexahistidine tag and purified using Ni-NTA (Fig.11) and gelfiltration (Fig.12) columns. | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <h3>After Ni-NTA column:</h3> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 11 </strong>SurA after purification with Ni-NTA column | ||

| + | L - PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, 1 - Protein loaded on Ni-NTA Column, Lane 2 – Flow through fraction, 3 - washing fraction, 4-9 elution fractions | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>After gelfiltration</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 12 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 12 </strong>SurA fractions after gelfiltration | ||

| + | L - PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder, 1-9 elution fractions | ||

| + | <H2>Folding assay</H2> | ||

| + | <p>To determine whether the purified proteins act as expected we conducted a specific a folding assay. Proteins possessing β-barrel structures exhibit a unique characteristic - when mixed with SDS (for SDS-PAGE) but unboiled, the β-barrel structure remains intact, which causes the protein to move differently in the SDS-PAGE gel in comparison to the same protein lacking these structures - which occurs when it is denatured or did not originally fold. Exploiting this characteristic makes it possible to observe and quantify protein folding levels.</p> | ||

| + | <p>For the first experiment we observed if BamB and BamCDE can incorporate the unfolded BamA protein into the membrane and reconstitute the complete BAM complex. This was accomplished by incubating SurA with BamA denatured in urea, then transferring it into a solution featuring liposomes, BamB and BamCDE, then further incubating for 2 hours. As BamA was expressed with a his-tag, we performed a blot to determine the level of protein folding (Fig. 13). </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Fig. 13 | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <strong>Fig. 13</strong> Western blot of BamA folding. 1U - sample 1 unboiled, 1B - sample 1 boiled, 2U - sample 2 unboiled, 2B - sample 2 boiled, L - ladder | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>As we can see from the results, after only 2 hours of incubation over 50% of BamA was processed and correctly folded, which is an indicator of proper functionality. At higher concentrations or within more enclosed environments, such as encapsulated within the liposome, efficiency is bound to increase.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h1>Conclusions</h1> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <p>We managed to successfully isolate the BAM protein complex at a high purity with relatively few steps. The BAM complex not only shows activity in vitro, it shows efficient activity within the presence of liposomes, which shows that it is functional and suitable for our system. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <h1>Discussion</h1> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <p>The study of MPs is and continues to be a difficult area of study, due to the sheer difficulty in handling them. As we have emphasized before, the integration of MP’s is a particularly pronounced issue, being borderline impossible for some cases in vitro. However, we have managed to demonstrate, that with our newly designed approach utilizing the BAM complex, the SynDrop system can allow for much more efficient insertion of MP’s as well as greatly expanding the total amount of viable MP’s for high throughput in vitro studies.</p> | ||

| + | <h2>References</h2> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <Li>White, S. & Wimley, W. MEMBRANE PROTEIN FOLDING AND STABILITY: Physical Principles. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure 28, 319-365 (1999).</Li> | ||

| + | <li>Noinaj, N., Rollauer, S. & Buchanan, S. The β-barrel membrane protein insertase machinery from Gram-negative bacteria. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 31, 35-42 (2015). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Fleming, P. et al. BamA POTRA Domain Interacts with a Native Lipid Membrane Surface. Biophysical Journal 110, 2698-2709 (2016). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Hussain, S. & Bernstein, H. The Bam complex catalyzes efficient insertion of bacterial outer membrane proteins into membrane vesicles of variable lipid composition. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293, 2959-2973 (2018). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Driessen, A. & Nouwen, N. Protein Translocation Across the Bacterial Cytoplasmic Membrane. Annual Review of Biochemistry 77, 643-667 (2008). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Sklar, J., Wu, T., Kahne, D. & Silhavy, T. Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia coli. Genes & Development 21, 2473-2484 (2007). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> Bennion, D., Charlson, E., Coon, E. & Misra, R. Dissection of β-barrel outer membrane protein assembly pathways through characterizing BamA POTRA 1 mutants of Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology 77, 1153-1171 (2010). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Gu, Y. et al. Structural basis of outer membrane protein insertion by the BAM complex. Nature 531, 64-69 (2016). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Hagan, C., Westwood, D. & Kahne, D. Bam Lipoproteins Assemble BamA in Vitro. Biochemistry 52, 6108-6113 (2013). | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | </p>- | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</section> | </section> | ||

Revision as of 15:05, 8 November 2018

Design and Results

Results

Cell-free, synthetic biology systems open new horizons in engineering biomolecular systems which feature complex, cell-like behaviors in the absence of living entities. Having no superior genetic control, user-controllable mechanisms to regulate gene expression are necessary to successfully operate these systems. We have created a small collection of synthetic RNA thermometers that enable temperature-dependent translation of membrane proteins, work well in cells and display great potential to be transferred to any in vitro protein synthesis system.

Fig. 1 Simplified structure of scFv Antibody

Fig. 1 Simplified structure of scFv Antibody

Fig. 2 Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.

Fig. 2 Scheme of scFv_antiVLY and VLY interaction. Left- scFv_antiVLY binds to VLY, erythrocytes stay intact, Right- scFv_antiVLY does not bind and VLY lyse erythrocytes.