| (278 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<style> | <style> | ||

| − | #expt1, #expt2, #expt3, #expt4, #expt5, #expt6,#expt7,#expt8 { | + | #expt1, #expt2, #expt3, #expt4, #expt5, #expt6,#expt7,#expt8,#expt9 { |

width:100%; | width:100%; | ||

height:5px; | height:5px; | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

font-family:"Varela Round", sans-serif; | font-family:"Varela Round", sans-serif; | ||

color:#374785; | color:#374785; | ||

| − | |||

} | } | ||

| Line 90: | Line 89: | ||

box-sizing: border-box; | box-sizing: border-box; | ||

} | } | ||

| + | .caption p{ | ||

| + | margin:auto !important; | ||

| + | |||

| + | } | ||

</style> | </style> | ||

</head> | </head> | ||

| Line 124: | Line 127: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p> The PixCell Construct consists of a repurposed version of the soxRS regulon from E. coli, consisting of SoxR and GFP being expressed from either side of the pSoxR/pSoxS bidrirectional promoter. pSoxR provides constitutive expression of SoxR. When oxidised, either directly by redox-cycling molecule or by oxidative stress, SoxR binds and activates transcription of GFP downstream of pSoxS.</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | |

| − | + | <div class="panel expt1p"> | |

| + | |||

| + | <p> The Pixcell construct was designed to test whether we could control the expression of GFP by controlling the oxidation state of SoxR through our electrochemical set up.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt1p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt1p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p> Using the Golden Gate assembly method, with two inserts; the sensing portion of the soxRS regulon and GFP, which were originally amplified out from the E. coli genome and a storage vector respectively, the construct was assembled. Gel electrophoresis showed that a construct of approximately the right length was produced and the construct was then sequence verified. </p> |

| − | + | <img class="figure" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b3/T--Imperial_College--PixcellConstructGel.png"> | |

| − | < | + | </br></br> |

| − | + | ||

<div class="caption"> | <div class="caption"> | ||

| − | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> PCR results of | + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> PCR results from the amplification of the entire construct</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>In order to lower the basal level of GFP expression a novel degradation tag was added. Therefore, any increase in GFP expression induced by the oxidation of SoxR would be more predominant.</p> |

| − | + | <img class="center" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/6d/T--Imperial_College--PixcellConstructResults.png" alt="" width="40%";> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b> Illustration of the PixCell Construct</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <img class="center" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/26/T--Imperial_College--PixcellConstructDEGTAG.png" alt="" width="40%";> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b> Illustration of the PixCell Construct DegTag</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 156: | Line 170: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt1p"> | <div class="panel expt1p"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p> The PixCell construct enables us to test whether we can control gene expression by controlling the oxidation state of SoxR. The PixCell construct DegTag enables the system to be more dynamic in that seeing the system switch from on to off is quicker. </p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| Line 164: | Line 178: | ||

<!--Start Experiment 2--> | <!--Start Experiment 2--> | ||

<div id="expt2"> | <div id="expt2"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="underbold" >Characterizing Pixcell Constructs</h4> | + | <h4 class="underbold">Characterizing Pixcell Constructs</h4> |

<div onclick="expandAll('expt2p');" class="expandButton"> | <div onclick="expandAll('expt2p');" class="expandButton"> | ||

<p class="expand expt2p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | <p class="expand expt2p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | ||

| Line 171: | Line 185: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>PixCell, the 2018 Imperial College iGEM team, characterised this device in a series of steps in order to make it respond to an electrical stimulus. The device functions by oxidising pyocyanin and ferrocyanide with an electrode. Oxidised pyocyanin in turn oxidises SoxR to activate the device. The potential also oxidises ferrocyanide to ferricyanide, allowing electrons to be drawn away from pyocyanin via the quinone pool to amplify this response. Full growth curves and GFP expression profiles with standard error bars for each construct at each redox-molecule concentration are available in the “Supplementary Data” section. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt2p"> | <div class="panel expt2p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >These results demonstrate that the assembled PixCell circuit can be switched on by oxidative signals and switched off by reductive signals. These experimental data were also handed over the dry lab, where information about fold induction and degradation rates supported and further implemented the theoretical models.</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt2p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt2p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The construct was first tested with a range of pyocyanin concentrations (0-100μM) to measure the response of the system to the redox-cycling drug. High-concentrations of pyocyanin exert significant stress upon the cell leading to cell death. A working concentration of 2.5μM of pyocyanin is therefore recommended when using it as an inducer or within an electrogenetic device, as it provides an optimal trade-off between fold induction and cell viability. |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="floatleft2"> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/c7/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_PC1_OD.png" alt="" width="100%"> |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/47/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_PC2_OD.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b8/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_Pos_OD.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/90/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_Neg_OD.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> Growth of cells containing the construct in a range of pyocyanin concentrations, with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas. Above 5 uM of pyocyanin show reduced viability. Cells with the PixCell constructs survive more, as they have the SoxR adaptive response. </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/c6/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_PC1_GFP.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/68/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_PC2_GFP.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/cf/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_Pos_GFP.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7d/T--Imperial_College--Pyo_Neg_GFP.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b>GFP fluorescence normalised with respect to OD600 at a range of pyocyanin concentrations, with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas. At low pyocyanin concentration a significant increase in GFP is observed in cells containing the PixCell construct. GFP folds at high pyocyanin concentration due to reduced cell's viability.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <p>A significant sixfold induction in fluorescence was seen in the device when comparing values at 0μM and 2.5μM of pyocyanin, as shown in Fig. 3. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/0e/T--Imperial_College--pyo_response.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b>GFP fluorescence as a function of pyocyanin concentration, taken at steady state (900 mins), normalised with respect to OD600, and averaged over three biological replicas, for circuits with and without deg tag and with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Oxidisation of pyocyanin, without intentional induction, was observed in the aerobic environment, as evidenced by the response of the cells. To prevent this behaviour, sodium sulfite (an oxygen scavenger) was added to the medium to maintain an OFF state in the absence of deliberate induction. Without this innovation, the device could only work in anaerobic conditions, limiting the potential of electronic induction of gene expression. A final sodium sulfite concentration of 0.02% was selected for the electrogenetic system as it prevented GFP expression from an agar plate in aerobic conditions with 2.5μM pyocyanin and 2.5mM ferrocyanide. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/64/T--Imperial_College--pyoreducedsulfi.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 4.</b>Plate reader data showing absorbance at 390 nm (absorption peak of oxidised pyocyanin) as a function of sodium sulfite concentration. Addition of sodium sulfite reduces a solution of 125 uM pyocyanin dissolved in autoclaved water. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <p>We observed that the oxygen scavenger sodium sulfite reduces pyocyanyn in a linear relationship until a concentration of 2.5% sulfite added. At these concentrations, we observed electrochemical interference when perfoming square-wave voltammetry experiments. We hypothesised that sulfites could react with pyocyanin, producing pyocyanin sulfonate, which has an absorption peak at 400 nm | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7c/T--Imperial_College--pyosulpho.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 5.</b>OD390 (absorption peak of pyo-ox) and OD400 (absorption peak of pyocyanin sulfonate) as a function of sulfite concentration. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The results shown in figure 5 supported the hypothesis that pyocyanin sulfonate is produced at high sulfite concentration. Therefore, we performed the next experiments at sulfite concentrations between 0 and 0.03% (figure 6), which appeared to fall in the linear region of the graph. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/05/T--Imperial_College--Na2SO3_plates.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 6.</b> Agar plates of construct-bearing cells with varying sodium sulfite conditions, imaged under UV transluminescence, showing that 0.02% is sufficient to suppress unintentional induction. All the plates contain 2.5 uM pyocyanin and 2.5 mM ferrocyanide.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Next the concentration of ferrocyanide was optimised, as shown in figure 7. A range of ferrocyanide and ferricyanide concentrations (0-100mM) were tested using 2.5μM pyocyanin and 0.02% sodium sulfite. This was done in order to find a single concentration at which ferrocyanide would provide no GFP expression whereas ferricyanide would allow for a large induction of GFP expression. The final condition of 10mM was selected for an optimal fold change; these concentrations also did not significantly impact cell growth. A 10mM concentration of ferricyanide provided at least an order of magnitudefold induction of GFP expression compared to ferrocyanide. Therefore if bulk oxidation of ferrocyanide to ferricyanide could be achieved then gene expression could be electronically induced in aerobic conditions. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | + | <div class=“floatleft2”> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/c0/T--Imperial_College--ferri_response.png" alt="" width="100%"> | |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class=“floatleft2”> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fb/T--Imperial_College--ferro_response.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class=“clr”></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 7.</b>GFP fluorescence as a function of ferricyanide and ferrocyanide concentration, taken at steady state (700 mins), normalised with respect to OD600, and averaged over three biological replicas, for circuits with and without deg tag and the same controls as Fig. 1. Experiments performed at a sodium sulfite concentration of 0.02% and with 2.5μM pyocyanin.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>In figure 8, we demonstrate that the chosen conditions are sufficient to produce high GFP expression when oxidised ferricyanide is added into the plate and low GFP when the same concentration of reduced ferrocyanide is added.</p> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/98/T--Imperial_College--plates_final.png" alt="" width="100%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 8.</b>LB+ Agar plates containing 2.5 uM pyocyanin, 0.02 % sodium sulfite and 10 mM ferrocyanide (row above) and 10 mM ferricyanide (row below) containing the PixCell cnstructs and positive and negative controls.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 206: | Line 354: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt2p"> | <div class="panel expt2p"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>These experiments allowed us to demonstrate that our constructs are responsive to oxidising input and enabled us to identify the concentrations of redox-molecule. This allowed us to select a suitable chemical composition of 2.5uM Pyo, 0.02% sodium sulfite and 10mM ferrocyanide, which works both in liquid and solid cultures. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| Line 219: | Line 368: | ||

<p class="expand expt3p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | <p class="expand expt3p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | ||

<div class="expand" style="margin-right:5px;"> | <div class="expand" style="margin-right:5px;"> | ||

| + | |||

<i class="fa fa-angle-double-down expt3p"></i> | <i class="fa fa-angle-double-down expt3p"></i> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 227: | Line 377: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>To demonstrate the ability of our electrode set-up to selectively oxidise and reduce our redox modulators in solution, we investigated the redox status of the our redox molecules with square wave voltammetry (SWV) and by measuring the absorbance at 390 nm with a plate reader. SWV data showed that a voltage of +0.5 at the working electrode enables bulk oxidation, whereas a voltage of -0.4 allows bulk reduction. However, the presence of oxygen in aerobic environments interferes with the oxidation signal carried by the electrodes. Measuing optical absorbance at 390 nm with a plate reader, we then investigated the redox kinetics of pyocyanin in the presence of the reducing agent sodium sulfite. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt3p"> | <div class="panel expt3p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >These results show that our set-up is able to selectively and reversibly oxidise and reduce our redox modulators. Furthermore , by performing these electrochemistry experiments, we proved that addition of the reducing agent sodium sulfite enables complete chemical reduction of the system, even in aerobic environment. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt3p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt3p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/4b/T--Imperial_College--squarewavevoltammetrysetupworkingel.png" alt=""width="100%";> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> Square-wave voltammetry setup</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The above setup was used to perform square-wave voltammetry to investigate bulk oxidation and reduction of our system. The setup was controlled using a multichannel potentiostat connected to a computer. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/40/T--Imperial_College--electrochemistryscreenshot.png" alt=""width="100%";> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2. Square-wave voltammetry of redox modulator</b> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <p>The graphs above summarise the results showing that our system was consistently bulk reduced at -0.3V and bulk oxidised at +0.5V. The addition of Sulfite and cell containing the pixCell construct did not significantly alter the reduction and oxidation profile. These results led us to chose +0.5V as our oxidising potential in the following experiments testing the spatial electronic control of gene induction.</p> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/6f/T--Imperial_College--AmpData3.png" alt="" width="100%";> | ||

<div class="caption"> | <div class="caption"> | ||

| − | <p><b>Figure | + | <p class="center"><b>Figure 3.</b> Amperometry of the final plate conditions </p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | Amperometry was performed on plates containing 2.5uM Pyocyanin, 10mM FCN(R), Ampicillin, Kanamycin, 0.02% sulfite and E. coli containing PixCell construct Deg Tag. The results show that the current decays exponentially until a steady state is reached indicating bulk oxidation of redox modulators. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt3p"> | <div class="panel expt3p"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>These results describe the first ever aerobic electrogenetic control system, that works both in liquid and solid E. coli cultures. </p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

<!--End Experiment--> | <!--End Experiment--> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<!--Start Experiment 4--> | <!--Start Experiment 4--> | ||

| Line 279: | Line 453: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Here we demonstrated the first spatial activation of gene expression using electronic control. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt4p"> | <div class="panel expt4p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >The results below serve as proof-of-concept for our electrode set-up </p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt4p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt4p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>An electrode rig was set up to apply the potentials identified above to cells grown on an agar plate containing the final reaction condition of 2.5μM pyocyanin, 0.02% sodium sulfite and 10mM ferrocyanide. Redox reactions only occur at the electrode surface during an electrochemistry experiment, meaning that oxidised pyocyanin and ferrocyanide were only produced in close proximity to the working electrode upon the application of a +0.5V pulse. |

| − | + | ||

| + | Fluorescence images of agar plates clearly show localised expression of GFP around the working electrode (W), as observed in fig. 4 and 5. This not only shows that the device allows for electronic control of gene expression, but also demonstrates high spatial control meaning it can be used for programmable spatial patterning of cell populations. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| Line 296: | Line 473: | ||

<div class="center"> | <div class="center"> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <br/><br/> | + | </br></br> |

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/5/59/T--Imperial_College--Setup_of_the_electrode_rig_sch.png" alt="" width="90%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> Setup of the electrode rig for the electronic control of spatial gene induction</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d9/T--Imperial_College--platepulsingsetup.jpeg" alt="" width="50%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b> Image of the electrode rig placed in the incubator. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Figures 1 and Image 2 illustrate the setup of the electrode rig. The working, counter and reference electrodes are penetrating the plate through holes. Cells were plated onto an agar plate containing the final working concentrations: 10mM FCN(R), 2.5 uM pyocyanin, 0.03% sulfite, ampicillin and kanamycin. Agar is fully covering the electrodes which are controlled by a potentiostat. An oxidising potential of +0.5% was applied. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3e/T--Imperial_College--platepulsingsetup2.jpeg" alt="" width="70%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b> Expected outcome for the electronic control of gene expression on an agar plate</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Figure 3 illustrates the expected increased fluorescence around the working electrode. The oxidising potential results in bulk oxidation and activation of our system. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/f5/T--Imperial_College--PoP_gfp.JPEG" alt="" width="70%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 4.</b> GFP expression after electric stimulation</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>We demonstrated elevated GFP expression around the working electrode in figure 4. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/84/T--Imperial_College--same_adj_0.5.JPG" alt="" width="70%"; > | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/84/T--Imperial_College--same_adj_0.5.JPG" alt="" width="70%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 5.</b> Comparison of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after application of an oxidising potential. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>We next investigated GFP expression of PixCell Construct and PixCell Construct Deg Tag relative to the negative control (DJ901) and the positive control which constitutively expresses GFP. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fluorescence image analysis shows increased fluorescence around the working electrodes demonstrating electronic control of spatial gene expression. The addition of a degradation tag to GFP substantially reduces background fluorescence. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b4/T--Imperial_College--pixcellconstructworkingelectrode.png" alt="" width="100%"; > | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/96/T--Imperial_College--3dsurfaceplotpixcelldegtagworking2.png" alt="" width="100%"; > | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2d/T--Imperial_College--3dsurfaceplotposcontrol.jpeg" alt="" width="100%"; > | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="floatleft2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/85/T--Imperial_College--3dsurfaceplotnegcontrol.jpeg" alt="" width="100%"; > | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 6.</b> 3D surface plot showing relative fluorescence of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after electric stimulation. Clear peaks are evident at the working electrode sites for cells containing the PixCell Constructs.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>To better visualise the results 3D surface plots were made showing GFP expression in the z axis. GFP expression level from the positive and negative control was used to set a relative scale of GFP expression. Peaks around the working electrodes clear indicate increased GFP expression. PixCell construct Deg Tag showed lower background fluorescence compared to PixCell construct. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8b/T--Imperial_College--_Same_adj_-0.3.jpg" alt="" width="70%"; > | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8b/T--Imperial_College--_Same_adj_-0.3.jpg" alt="" width="70%"; > | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 7.</b> Comparison of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after application of a reducing potential</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | < | + | </br></br> |

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <p>Next the 4 cell types were exposed to a reducing potential of -0.3V (figure 7). Working electrodes do not show increased fluorescence. Higher background fluorescence in the plate with cells containing PixCell Construct compared to the the previous fluorescence images exposed to an oxidising potential is due to variation in spreading. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/e/ee/T--Imperial_College--_Pyo_plate_final.jpg" alt="" width="40%"; > | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/e/ee/T--Imperial_College--_Pyo_plate_final.jpg" alt="" width="40%"; > | ||

| − | + | <div class="caption"> | |

| + | <p><b>Figure 8. </b>GFP expression on a plate with final conditions in the absence of pyocyanin</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | </br></br> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>After successfully inducing spatially controlled activation of gene expression the system was tested in the absence of the redox modulator pyocyanin. This suggests that there is an electrode-induced mechanism for triggering the pSoxS pathway in the absence of pyocyanin. The plate contains 10mM FCN(R), 0.02% sulfite, Ampicillin, Kanamycin. Results show that increased expression levels of GFP can be achieved around the working electrode in the absence of pyocyanin. Further fine tuning of the system will be required to achieve the level of precision obtained on a plate containing our final working conditions. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 333: | Line 595: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt4p"> | <div class="panel expt4p"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>These results demonstrate precise electronic control of spatial gene expression, in solid cultures grown in aerobic condition.</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

<!--End Experiment--> | <!--End Experiment--> | ||

| − | <h3>Building and Characterizing the | + | <h3>Building and Characterizing the PixCell Library</h3> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div id="expt5"></div> | |

<h4 class="underbold" >Creating the Sox Library</h4> | <h4 class="underbold" >Creating the Sox Library</h4> | ||

<div onclick="expandAll('expt5p');" class="expandButton"> | <div onclick="expandAll('expt5p');" class="expandButton"> | ||

| Line 353: | Line 615: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | + | <p>The PixCell part library consists of 5 SoxR transcription factors and 8 pSoxS promoters which were created for construction of electrogenetic circuits with variable activity. This allows for control of this system on both the genetic and the electrochemical layer. SoxR transcription factors were obtained from a series of homologues from non-pathogenic species. pSoxS was completely rengineered as a promoter. The promoter was made unidirectional by knocking out the upstream constitutively active pSoxS portion, a terminator was placed upstream to allow for efficient tandem assemblies and a downstream ribozyme was added to remove context dependency. Promoters were either sourced from homologues in non-pathogenic bacteria or were produced by conservative mutations to the consensus sequences and SoxR binding site. The library includes a mutant promoter which provides transcriptional repression rather than activation. | |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="clr"></div> | |

| + | |||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt5p"> | <div class="panel expt5p"> | ||

| − | + | <p >These results expand the electrogenetic synthetic biology toolkit.</p> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="clr"></div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | |

| − | + | <div class="panel expt6p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="center"> | |

| − | </div> | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/c1/T--Imperial_College--SBOL_table.png" alt="" width="40%"> |

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b>Parts were synthesised with prefix and suffixes specific to the BASIC assembly method. A modified submission vector is provided with the library which allows for assembly of BASIC parts into the standardised BioBrick pSB1C3 vector, allowing for the stored parts to be compatible with both assembly standards. All library parts were assembled into this vector and growth curves of cells containing these storage plasmids exhibited no cytotoxicity.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9b/T--Imperial_College--screenshotheatmap.png" alt="" width="60%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b>The BASIC assembly method was used for high-throughput assembly of every promoter with every transcription factor to test all possible activities achievable with the library. BASIC uses standardised linkers that ligate onto the sticky ends of parts that have been digested with BsaI. These linkers stitch the parts together to assemble constructs. All constructs were assembled in low-medium copy number p15A vectors (in order to reduce any cytotoxicity) with SoxR being expressed from an improved version of the BBa_J23101 promoter, with superfolder-GFP being used as a reporter. SoxR and GFP were expressed from strong RBSs contained within the linkers used to assemble the constructs. </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a5/T--Imperial_College--Results_diagram.png" alt="" width="70%"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b>Diagram of BASIC assembly workflow for library characterization </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<!--End Experiment--> | <!--End Experiment--> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<!--Start Experiment 6--> | <!--Start Experiment 6--> | ||

<div id="expt6"></div> | <div id="expt6"></div> | ||

| − | <h4 class="underbold" > | + | <h4 class="underbold" >Characterizing the Sox Library</h4> |

<div onclick="expandAll('expt6p');" class="expandButton"> | <div onclick="expandAll('expt6p');" class="expandButton"> | ||

<p class="expand expt5p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | <p class="expand expt5p colorChange" style="font-size:25px;padding-top:1px;" >Access All</p> | ||

| Line 405: | Line 680: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | |

| + | <p>All assembled constructs were transformed into DH5-alpha with single colonies being grown for 15 hours with cells being grown in LB with either 0μM and 2.5μM pyocyanin. The normalised fluorescence from each cell was then calculated and compared. Firstly all fluorescence values were divided by the fluorescence of the library seed (BBa_K2862006 + BBa_K2862014) which is made frdom our versions of the native E. coli SoxR and pSoxS. This gave an RPU scale giving a range of promoter activities between 0-2.17 RPUs, exhibiting tunability of our system. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt6p"> | <div class="panel expt6p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >These results allowed us to evaluate whether we had created parts that could be used in a modular fashion</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt6p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt6p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="center"> | |

| − | + | <img src=" https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/c/c5/T--Imperial_College--libheatmaps.png" alt="" width="90%"> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="caption"> | |

| − | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> | + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> On the left, the difference between fluorescence at 2.5μM and 0μM of pyocyanin was also calculated. This not only showed strong inductions from some library members, but also showed that for certain transcription factors the repressor pSoxS mutant was functional. This allows for selection of a SoxR-pSoxS pairings with a specific induction strength. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/2c/T--Imperial_College--Lib_A1_OD.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d0/T--Imperial_College--Lib_Pos_OD.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/2/21/T--Imperial_College--Lib_Neg_OD.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="caption"> | |

| − | + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b>OD600 values for library seed, positive and negative controls at increasing pyocyanin concentration</p> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7a/T--Imperial_College--Lib_A1_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3c/T--Imperial_College--Lib_Pos_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/fd/T--Imperial_College--Lib_Neg_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%"> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <p>Taking the steady state fluorescence values we can show GFP expression (and therefore construct activity) as a function of pyocyanin activity. This shows a standard sigmoidal behaviour as predicted by our model and exhibited by PixCell Construct. | |

| − | + | </p> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="center"> | |

| − | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/96/T--Imperial_College--albibabbo.png" alt="" width="50%"> | |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| Line 442: | Line 743: | ||

| − | <h3>Testing | + | <h3>Testing Alternative Non-toxic Redox Modulators</h3> |

<!--Start Experiment 7--> | <!--Start Experiment 7--> | ||

<div id="expt7"></div> | <div id="expt7"></div> | ||

| Line 457: | Line 758: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Our electrogenetic control system relies on the electron carrying action of the redox-cycling drug pyocyanin, which is a toxic metabolite synthesised by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This poses limitations to our system, with regards to safety and possible applications. Therefore, we searched in the literature for alternative SoxR inducers and and tested potential non-toxic alternatives. Shown below are the characterization data for the best candidate alternative: phenazine, methosulfate. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt7p"> | <div class="panel expt7p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >These results demonstrate the first ever use of PMS as a non-toxic electrogenetic inducer.</p> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt7p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt7p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The above setup was used to perform Sqaure-wave voltammetry confirming that ferrocyanide was bulk reduced at -0.3V and bulk oxidised at +0.5V as this was the voltage at which current peaked. </p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="caption"> | <div class="caption"> | ||

| − | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> | + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> Phenazine as as Cheaper, Non-toxic Redox Modulator</p> |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/77/T--Imperial_College--PMSelectrochemistry.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b> OD600 as a function of time and PMS concentration</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b6/T--Imperial_College--PMS_PC2_OD.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/4/49/T--Imperial_College--PMS_Pos_OD.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/db/T--Imperial_College--PMS_Neg_OD.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/b/b7/T--Imperial_College--PMS_PC2_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/88/T--Imperial_College--PMS_Pos_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/6a/T--Imperial_College--PMS_Neg_GFP.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 5.</b> Phenazine induces GFP expression in PixCell Patterning Circuits</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/1/10/T--Imperial_College--phenazine_response.png" alt="" width="50%";> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 6.</b> Phenazine induces GFP expression in PixCell Patterning Circuits</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 488: | Line 819: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt7p"> | <div class="panel expt7p"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>These results demonstrates the SoxR/pSoxS system that we devised, can be used a non-toxic and effective tool for chemical, as well as electronic, gene induction. PMS is also incredibly cheap, being 40,000x cheaper than pyocyanin, ~190x cheaper than arabinose and ~29x cheaper than aTc per reaction. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| Line 509: | Line 841: | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | <div type="button" class="accordion"> Description </div> | ||

<div class="description"> | <div class="description"> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>In order to test our PixCell electrogenetic part library we constructed a biocontainment device to prototype one of our proposed applications. This was constructed using an existing part in the iGEM registry: the growth inhibitor Gp2 (BBa_K1893019). By placing this downstream of pSoxS (BBa_K2862006) and expressing SoxR (BBa_K2862014) from a constitutive promoter (BBa_K2862019) we could inhibit cell growth in DH5a in the oxidising conditions we produced from our electrochemical set up. We envisioned this being used with our array in a biocontainment device in which any cells that spread to the edges of the device have their growth seized by an oxidising potential. This device could be used to prevent the accidental release of GMOs, much like how electric fences are used to restrain animals. |

| + | |||

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Relevance</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt8p"> | <div class="panel expt8p"> | ||

| − | <p > | + | <p >These results serve as proof of concepts for the biocontainment application, as described in the “Applications” sections |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion">Results</div> | ||

<div class="panel expt8p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | <div class="panel expt8p" style="transition:max-height 1s ease-in-out;"> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="caption"> | <div class="caption"> | ||

| − | <p><b>Figure 1.</b> | + | <p><b>Figure 1.</b>Gp2 growth curves (OD600 as a function of time in oxidised and reduced condition. Negative control)</p> |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/9/9e/T--Imperial_College--GC_gp2gp2.png" alt="" width="70%";> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 2.</b>Gp2 negative control (DH5a with same construct but no Gp2) growth curves</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="center"> | |

| − | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7a/T--Imperial_College--GC_gp2gp2neg.png" alt="" width="70%";> | |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </br></br> | ||

| + | <div class="caption"> | ||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3.</b>Effect of Gp2 on growth after 1000 min in oxidising vs reducing environment</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/35/T--Imperial_College--gp2bar.png" alt="" width="70%";> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <div class="clr"></div> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>When looking at the steady state OD600 values of these constructs a clear significant ~2-fold reduction is seen in the application construct in oxidising conditions. Furthermore there is no difference between the growth of the reducing condition and the controls. This not only provides a proof-of concept for out application, but also proves the system is not significantly leaky. This means it is feasible to use a higher copy number plasmid or more toxic gene (such as MazF) in this device to provide an even more effective biocontainment device. .</p> |

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | <div type="button" class="accordion" >Summary</div> | ||

| − | <div class="panel | + | <div class="panel expt8p"> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>With some improvement, and when used in combination with the PixCell electrode array, this biocontainment device could be used for biocontainment of GMOs in contained-use devices. |

| + | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="clr"></div> | <div class="clr"></div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<script> | <script> | ||

| Line 643: | Line 951: | ||

| − | + | ||

</body> | </body> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:37, 2 November 2018

Results

Building and Testing Pixcell Constructs

Assembling the Pixcell Constructs

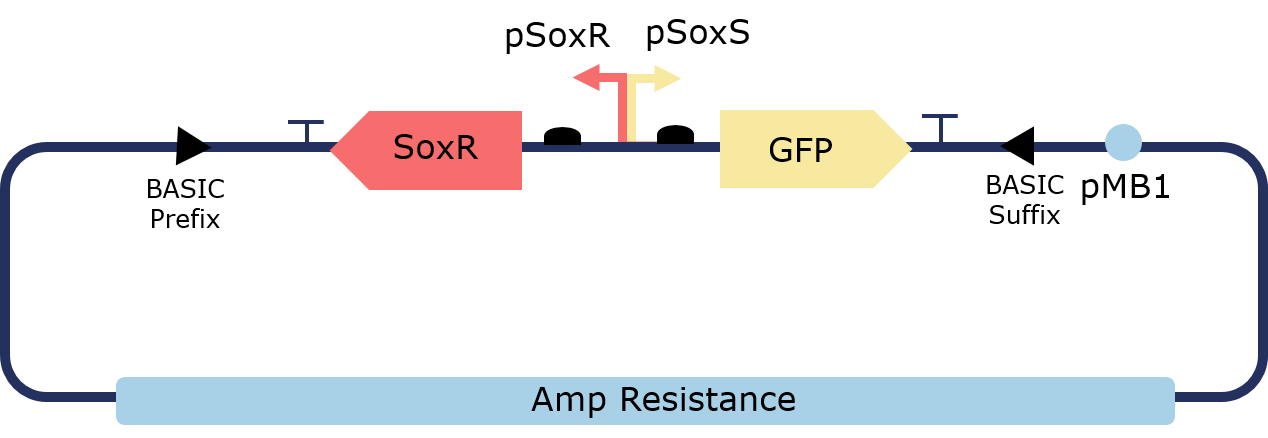

The PixCell Construct consists of a repurposed version of the soxRS regulon from E. coli, consisting of SoxR and GFP being expressed from either side of the pSoxR/pSoxS bidrirectional promoter. pSoxR provides constitutive expression of SoxR. When oxidised, either directly by redox-cycling molecule or by oxidative stress, SoxR binds and activates transcription of GFP downstream of pSoxS.

The Pixcell construct was designed to test whether we could control the expression of GFP by controlling the oxidation state of SoxR through our electrochemical set up.

Using the Golden Gate assembly method, with two inserts; the sensing portion of the soxRS regulon and GFP, which were originally amplified out from the E. coli genome and a storage vector respectively, the construct was assembled. Gel electrophoresis showed that a construct of approximately the right length was produced and the construct was then sequence verified.

Figure 1. PCR results from the amplification of the entire construct

In order to lower the basal level of GFP expression a novel degradation tag was added. Therefore, any increase in GFP expression induced by the oxidation of SoxR would be more predominant.

Figure 2. Illustration of the PixCell Construct

Figure 3. Illustration of the PixCell Construct DegTag

The PixCell construct enables us to test whether we can control gene expression by controlling the oxidation state of SoxR. The PixCell construct DegTag enables the system to be more dynamic in that seeing the system switch from on to off is quicker.

Characterizing Pixcell Constructs

PixCell, the 2018 Imperial College iGEM team, characterised this device in a series of steps in order to make it respond to an electrical stimulus. The device functions by oxidising pyocyanin and ferrocyanide with an electrode. Oxidised pyocyanin in turn oxidises SoxR to activate the device. The potential also oxidises ferrocyanide to ferricyanide, allowing electrons to be drawn away from pyocyanin via the quinone pool to amplify this response. Full growth curves and GFP expression profiles with standard error bars for each construct at each redox-molecule concentration are available in the “Supplementary Data” section.

These results demonstrate that the assembled PixCell circuit can be switched on by oxidative signals and switched off by reductive signals. These experimental data were also handed over the dry lab, where information about fold induction and degradation rates supported and further implemented the theoretical models.

The construct was first tested with a range of pyocyanin concentrations (0-100μM) to measure the response of the system to the redox-cycling drug. High-concentrations of pyocyanin exert significant stress upon the cell leading to cell death. A working concentration of 2.5μM of pyocyanin is therefore recommended when using it as an inducer or within an electrogenetic device, as it provides an optimal trade-off between fold induction and cell viability.

Figure 1. Growth of cells containing the construct in a range of pyocyanin concentrations, with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas. Above 5 uM of pyocyanin show reduced viability. Cells with the PixCell constructs survive more, as they have the SoxR adaptive response.

Figure 2.GFP fluorescence normalised with respect to OD600 at a range of pyocyanin concentrations, with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas. At low pyocyanin concentration a significant increase in GFP is observed in cells containing the PixCell construct. GFP folds at high pyocyanin concentration due to reduced cell's viability.

A significant sixfold induction in fluorescence was seen in the device when comparing values at 0μM and 2.5μM of pyocyanin, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.GFP fluorescence as a function of pyocyanin concentration, taken at steady state (900 mins), normalised with respect to OD600, and averaged over three biological replicas, for circuits with and without deg tag and with untransformed DJ901 as a negative control and DJ901 transformed with a GFP expression cassette as a positive control. Data obtained from three biological replicas.

Oxidisation of pyocyanin, without intentional induction, was observed in the aerobic environment, as evidenced by the response of the cells. To prevent this behaviour, sodium sulfite (an oxygen scavenger) was added to the medium to maintain an OFF state in the absence of deliberate induction. Without this innovation, the device could only work in anaerobic conditions, limiting the potential of electronic induction of gene expression. A final sodium sulfite concentration of 0.02% was selected for the electrogenetic system as it prevented GFP expression from an agar plate in aerobic conditions with 2.5μM pyocyanin and 2.5mM ferrocyanide.

Figure 4.Plate reader data showing absorbance at 390 nm (absorption peak of oxidised pyocyanin) as a function of sodium sulfite concentration. Addition of sodium sulfite reduces a solution of 125 uM pyocyanin dissolved in autoclaved water.

We observed that the oxygen scavenger sodium sulfite reduces pyocyanyn in a linear relationship until a concentration of 2.5% sulfite added. At these concentrations, we observed electrochemical interference when perfoming square-wave voltammetry experiments. We hypothesised that sulfites could react with pyocyanin, producing pyocyanin sulfonate, which has an absorption peak at 400 nm

Figure 5.OD390 (absorption peak of pyo-ox) and OD400 (absorption peak of pyocyanin sulfonate) as a function of sulfite concentration.

The results shown in figure 5 supported the hypothesis that pyocyanin sulfonate is produced at high sulfite concentration. Therefore, we performed the next experiments at sulfite concentrations between 0 and 0.03% (figure 6), which appeared to fall in the linear region of the graph.

Figure 6. Agar plates of construct-bearing cells with varying sodium sulfite conditions, imaged under UV transluminescence, showing that 0.02% is sufficient to suppress unintentional induction. All the plates contain 2.5 uM pyocyanin and 2.5 mM ferrocyanide.

Next the concentration of ferrocyanide was optimised, as shown in figure 7. A range of ferrocyanide and ferricyanide concentrations (0-100mM) were tested using 2.5μM pyocyanin and 0.02% sodium sulfite. This was done in order to find a single concentration at which ferrocyanide would provide no GFP expression whereas ferricyanide would allow for a large induction of GFP expression. The final condition of 10mM was selected for an optimal fold change; these concentrations also did not significantly impact cell growth. A 10mM concentration of ferricyanide provided at least an order of magnitudefold induction of GFP expression compared to ferrocyanide. Therefore if bulk oxidation of ferrocyanide to ferricyanide could be achieved then gene expression could be electronically induced in aerobic conditions.

Figure 7.GFP fluorescence as a function of ferricyanide and ferrocyanide concentration, taken at steady state (700 mins), normalised with respect to OD600, and averaged over three biological replicas, for circuits with and without deg tag and the same controls as Fig. 1. Experiments performed at a sodium sulfite concentration of 0.02% and with 2.5μM pyocyanin.

In figure 8, we demonstrate that the chosen conditions are sufficient to produce high GFP expression when oxidised ferricyanide is added into the plate and low GFP when the same concentration of reduced ferrocyanide is added.

Figure 8.LB+ Agar plates containing 2.5 uM pyocyanin, 0.02 % sodium sulfite and 10 mM ferrocyanide (row above) and 10 mM ferricyanide (row below) containing the PixCell cnstructs and positive and negative controls.

These experiments allowed us to demonstrate that our constructs are responsive to oxidising input and enabled us to identify the concentrations of redox-molecule. This allowed us to select a suitable chemical composition of 2.5uM Pyo, 0.02% sodium sulfite and 10mM ferrocyanide, which works both in liquid and solid cultures.

Electrochemistry of Redox Modulators

To demonstrate the ability of our electrode set-up to selectively oxidise and reduce our redox modulators in solution, we investigated the redox status of the our redox molecules with square wave voltammetry (SWV) and by measuring the absorbance at 390 nm with a plate reader. SWV data showed that a voltage of +0.5 at the working electrode enables bulk oxidation, whereas a voltage of -0.4 allows bulk reduction. However, the presence of oxygen in aerobic environments interferes with the oxidation signal carried by the electrodes. Measuing optical absorbance at 390 nm with a plate reader, we then investigated the redox kinetics of pyocyanin in the presence of the reducing agent sodium sulfite.

These results show that our set-up is able to selectively and reversibly oxidise and reduce our redox modulators. Furthermore , by performing these electrochemistry experiments, we proved that addition of the reducing agent sodium sulfite enables complete chemical reduction of the system, even in aerobic environment.

Figure 1. Square-wave voltammetry setup

The above setup was used to perform square-wave voltammetry to investigate bulk oxidation and reduction of our system. The setup was controlled using a multichannel potentiostat connected to a computer.

Figure 2. Square-wave voltammetry of redox modulator

The graphs above summarise the results showing that our system was consistently bulk reduced at -0.3V and bulk oxidised at +0.5V. The addition of Sulfite and cell containing the pixCell construct did not significantly alter the reduction and oxidation profile. These results led us to chose +0.5V as our oxidising potential in the following experiments testing the spatial electronic control of gene induction.

Figure 3. Amperometry of the final plate conditions

Amperometry was performed on plates containing 2.5uM Pyocyanin, 10mM FCN(R), Ampicillin, Kanamycin, 0.02% sulfite and E. coli containing PixCell construct Deg Tag. The results show that the current decays exponentially until a steady state is reached indicating bulk oxidation of redox modulators.

These results describe the first ever aerobic electrogenetic control system, that works both in liquid and solid E. coli cultures.

Spatial Electronic Control of Gene Induction

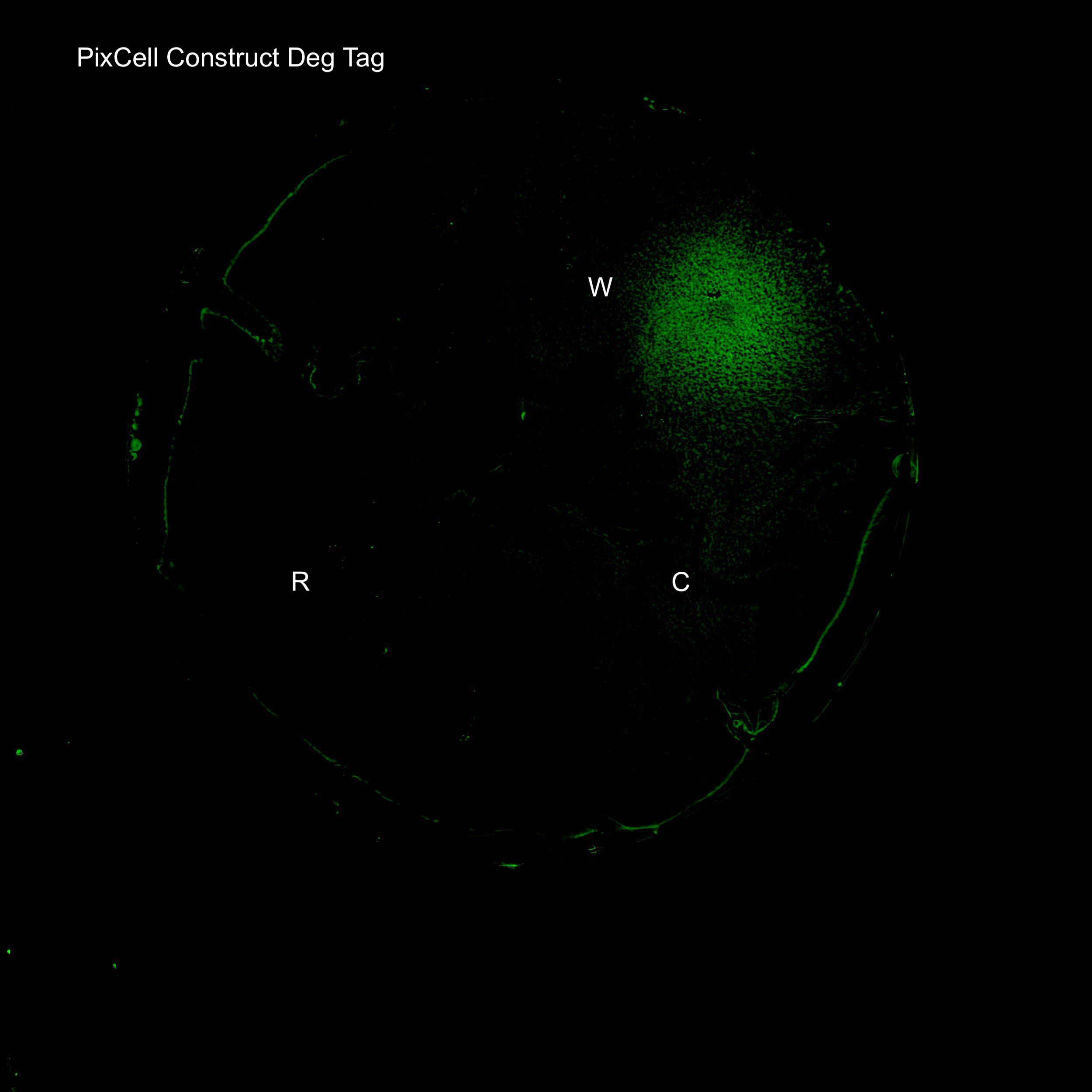

Here we demonstrated the first spatial activation of gene expression using electronic control.

The results below serve as proof-of-concept for our electrode set-up

An electrode rig was set up to apply the potentials identified above to cells grown on an agar plate containing the final reaction condition of 2.5μM pyocyanin, 0.02% sodium sulfite and 10mM ferrocyanide. Redox reactions only occur at the electrode surface during an electrochemistry experiment, meaning that oxidised pyocyanin and ferrocyanide were only produced in close proximity to the working electrode upon the application of a +0.5V pulse. Fluorescence images of agar plates clearly show localised expression of GFP around the working electrode (W), as observed in fig. 4 and 5. This not only shows that the device allows for electronic control of gene expression, but also demonstrates high spatial control meaning it can be used for programmable spatial patterning of cell populations.

Figure 1. Setup of the electrode rig for the electronic control of spatial gene induction

Figure 2. Image of the electrode rig placed in the incubator.

Figures 1 and Image 2 illustrate the setup of the electrode rig. The working, counter and reference electrodes are penetrating the plate through holes. Cells were plated onto an agar plate containing the final working concentrations: 10mM FCN(R), 2.5 uM pyocyanin, 0.03% sulfite, ampicillin and kanamycin. Agar is fully covering the electrodes which are controlled by a potentiostat. An oxidising potential of +0.5% was applied.

Figure 3. Expected outcome for the electronic control of gene expression on an agar plate

Figure 3 illustrates the expected increased fluorescence around the working electrode. The oxidising potential results in bulk oxidation and activation of our system.

Figure 4. GFP expression after electric stimulation

We demonstrated elevated GFP expression around the working electrode in figure 4.

Figure 5. Comparison of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after application of an oxidising potential.

We next investigated GFP expression of PixCell Construct and PixCell Construct Deg Tag relative to the negative control (DJ901) and the positive control which constitutively expresses GFP. Fluorescence image analysis shows increased fluorescence around the working electrodes demonstrating electronic control of spatial gene expression. The addition of a degradation tag to GFP substantially reduces background fluorescence.

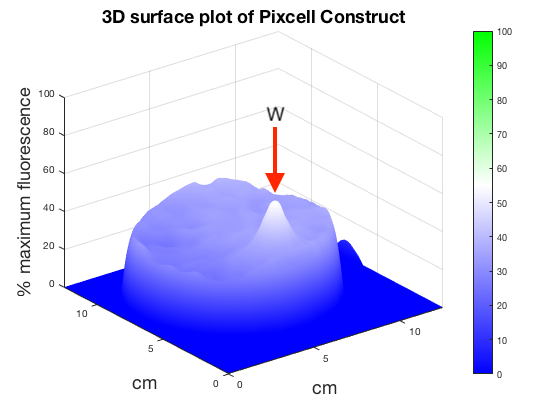

Figure 6. 3D surface plot showing relative fluorescence of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after electric stimulation. Clear peaks are evident at the working electrode sites for cells containing the PixCell Constructs.

To better visualise the results 3D surface plots were made showing GFP expression in the z axis. GFP expression level from the positive and negative control was used to set a relative scale of GFP expression. Peaks around the working electrodes clear indicate increased GFP expression. PixCell construct Deg Tag showed lower background fluorescence compared to PixCell construct.

Figure 7. Comparison of PixCell Construct, PixCell Construct Deg Tag, positive control and negative control after application of a reducing potential

Next the 4 cell types were exposed to a reducing potential of -0.3V (figure 7). Working electrodes do not show increased fluorescence. Higher background fluorescence in the plate with cells containing PixCell Construct compared to the the previous fluorescence images exposed to an oxidising potential is due to variation in spreading.

Figure 8. GFP expression on a plate with final conditions in the absence of pyocyanin

After successfully inducing spatially controlled activation of gene expression the system was tested in the absence of the redox modulator pyocyanin. This suggests that there is an electrode-induced mechanism for triggering the pSoxS pathway in the absence of pyocyanin. The plate contains 10mM FCN(R), 0.02% sulfite, Ampicillin, Kanamycin. Results show that increased expression levels of GFP can be achieved around the working electrode in the absence of pyocyanin. Further fine tuning of the system will be required to achieve the level of precision obtained on a plate containing our final working conditions.

These results demonstrate precise electronic control of spatial gene expression, in solid cultures grown in aerobic condition.

Building and Characterizing the PixCell Library

Creating the Sox Library

The PixCell part library consists of 5 SoxR transcription factors and 8 pSoxS promoters which were created for construction of electrogenetic circuits with variable activity. This allows for control of this system on both the genetic and the electrochemical layer. SoxR transcription factors were obtained from a series of homologues from non-pathogenic species. pSoxS was completely rengineered as a promoter. The promoter was made unidirectional by knocking out the upstream constitutively active pSoxS portion, a terminator was placed upstream to allow for efficient tandem assemblies and a downstream ribozyme was added to remove context dependency. Promoters were either sourced from homologues in non-pathogenic bacteria or were produced by conservative mutations to the consensus sequences and SoxR binding site. The library includes a mutant promoter which provides transcriptional repression rather than activation.

These results expand the electrogenetic synthetic biology toolkit.

Figure 1.Parts were synthesised with prefix and suffixes specific to the BASIC assembly method. A modified submission vector is provided with the library which allows for assembly of BASIC parts into the standardised BioBrick pSB1C3 vector, allowing for the stored parts to be compatible with both assembly standards. All library parts were assembled into this vector and growth curves of cells containing these storage plasmids exhibited no cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.The BASIC assembly method was used for high-throughput assembly of every promoter with every transcription factor to test all possible activities achievable with the library. BASIC uses standardised linkers that ligate onto the sticky ends of parts that have been digested with BsaI. These linkers stitch the parts together to assemble constructs. All constructs were assembled in low-medium copy number p15A vectors (in order to reduce any cytotoxicity) with SoxR being expressed from an improved version of the BBa_J23101 promoter, with superfolder-GFP being used as a reporter. SoxR and GFP were expressed from strong RBSs contained within the linkers used to assemble the constructs.

Figure 3.Diagram of BASIC assembly workflow for library characterization

Characterizing the Sox Library

All assembled constructs were transformed into DH5-alpha with single colonies being grown for 15 hours with cells being grown in LB with either 0μM and 2.5μM pyocyanin. The normalised fluorescence from each cell was then calculated and compared. Firstly all fluorescence values were divided by the fluorescence of the library seed (BBa_K2862006 + BBa_K2862014) which is made frdom our versions of the native E. coli SoxR and pSoxS. This gave an RPU scale giving a range of promoter activities between 0-2.17 RPUs, exhibiting tunability of our system.

These results allowed us to evaluate whether we had created parts that could be used in a modular fashion

Figure 1. On the left, the difference between fluorescence at 2.5μM and 0μM of pyocyanin was also calculated. This not only showed strong inductions from some library members, but also showed that for certain transcription factors the repressor pSoxS mutant was functional. This allows for selection of a SoxR-pSoxS pairings with a specific induction strength.

Figure 2.OD600 values for library seed, positive and negative controls at increasing pyocyanin concentration

Taking the steady state fluorescence values we can show GFP expression (and therefore construct activity) as a function of pyocyanin activity. This shows a standard sigmoidal behaviour as predicted by our model and exhibited by PixCell Construct.

Testing Alternative Non-toxic Redox Modulators

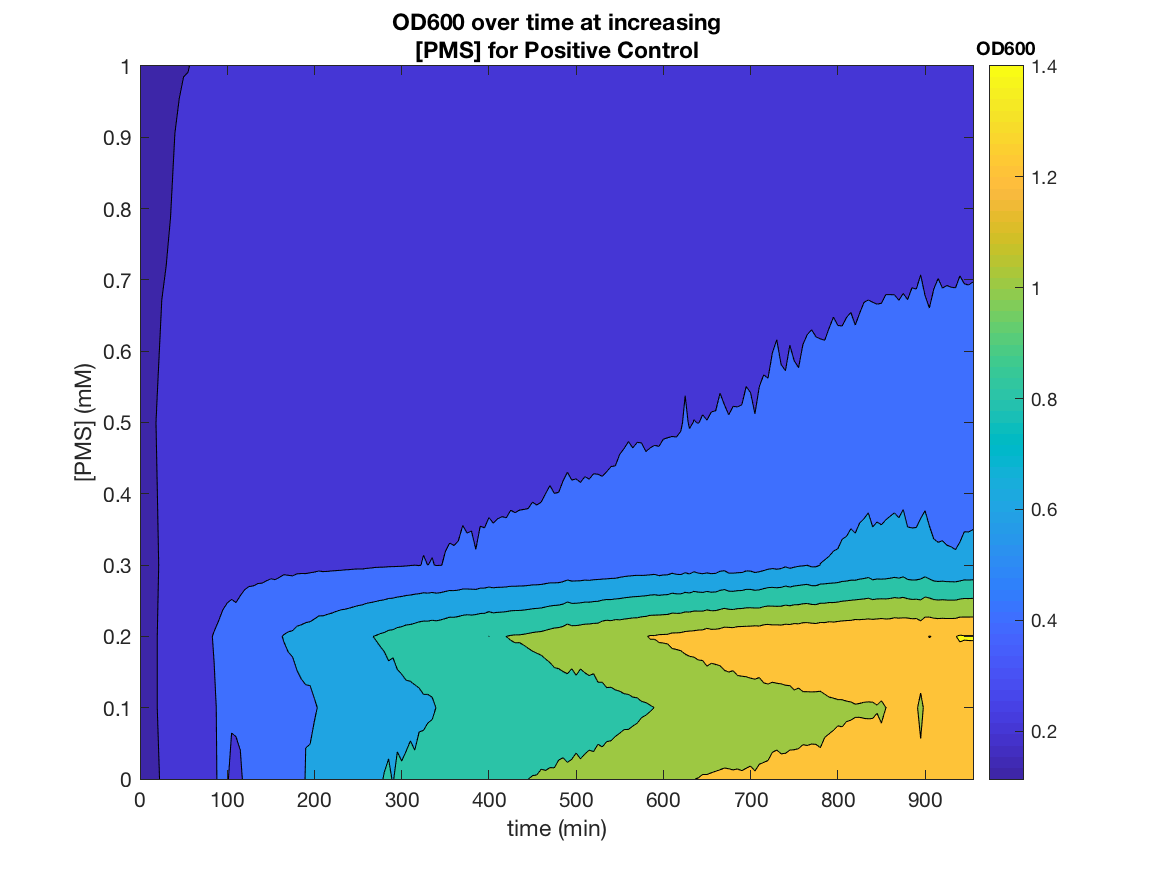

Testing Phenazine Methosulfate

Our electrogenetic control system relies on the electron carrying action of the redox-cycling drug pyocyanin, which is a toxic metabolite synthesised by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This poses limitations to our system, with regards to safety and possible applications. Therefore, we searched in the literature for alternative SoxR inducers and and tested potential non-toxic alternatives. Shown below are the characterization data for the best candidate alternative: phenazine, methosulfate.

These results demonstrate the first ever use of PMS as a non-toxic electrogenetic inducer.

The above setup was used to perform Sqaure-wave voltammetry confirming that ferrocyanide was bulk reduced at -0.3V and bulk oxidised at +0.5V as this was the voltage at which current peaked.

Figure 1. Phenazine as as Cheaper, Non-toxic Redox Modulator

Figure 2. OD600 as a function of time and PMS concentration

Figure 5. Phenazine induces GFP expression in PixCell Patterning Circuits

Figure 6. Phenazine induces GFP expression in PixCell Patterning Circuits

These results demonstrates the SoxR/pSoxS system that we devised, can be used a non-toxic and effective tool for chemical, as well as electronic, gene induction. PMS is also incredibly cheap, being 40,000x cheaper than pyocyanin, ~190x cheaper than arabinose and ~29x cheaper than aTc per reaction.

Applications

Biocontainment- Gp2 Growth Inhibition

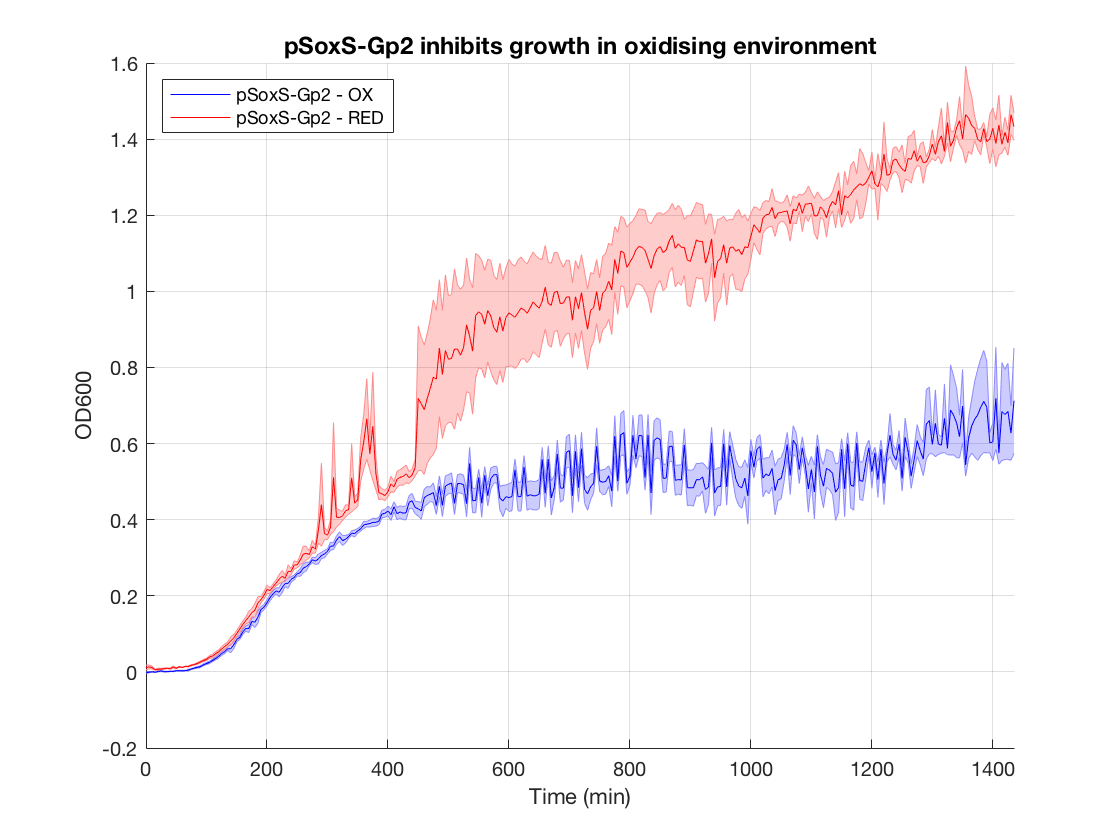

In order to test our PixCell electrogenetic part library we constructed a biocontainment device to prototype one of our proposed applications. This was constructed using an existing part in the iGEM registry: the growth inhibitor Gp2 (BBa_K1893019). By placing this downstream of pSoxS (BBa_K2862006) and expressing SoxR (BBa_K2862014) from a constitutive promoter (BBa_K2862019) we could inhibit cell growth in DH5a in the oxidising conditions we produced from our electrochemical set up. We envisioned this being used with our array in a biocontainment device in which any cells that spread to the edges of the device have their growth seized by an oxidising potential. This device could be used to prevent the accidental release of GMOs, much like how electric fences are used to restrain animals.

These results serve as proof of concepts for the biocontainment application, as described in the “Applications” sections

Figure 1.Gp2 growth curves (OD600 as a function of time in oxidised and reduced condition. Negative control)

Figure 2.Gp2 negative control (DH5a with same construct but no Gp2) growth curves

Figure 3.Effect of Gp2 on growth after 1000 min in oxidising vs reducing environment

When looking at the steady state OD600 values of these constructs a clear significant ~2-fold reduction is seen in the application construct in oxidising conditions. Furthermore there is no difference between the growth of the reducing condition and the controls. This not only provides a proof-of concept for out application, but also proves the system is not significantly leaky. This means it is feasible to use a higher copy number plasmid or more toxic gene (such as MazF) in this device to provide an even more effective biocontainment device. .

With some improvement, and when used in combination with the PixCell electrode array, this biocontainment device could be used for biocontainment of GMOs in contained-use devices.