| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

HUHF was expressed in <i>E. coli</i> DH5α. Therefore, 50 mL LB cultures in shaking flasks were inoculated from an overnight culture to achieve an OD<sub>600</sub> of 0.1. The cultures were cultivated at 37 °C and 140 rounds per minute (rpm). After growing to an OD<sub>600</sub> of 0.6-0.8, HUHF expression was induced with 1 % L-arabinose. After induction the flasks were incubated at 28 °C and 140 rpm for six hours. Samples were taken hourly for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/73/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--SDS_PAGE_LK.pdf">(SDS-PAGE)</a>. | HUHF was expressed in <i>E. coli</i> DH5α. Therefore, 50 mL LB cultures in shaking flasks were inoculated from an overnight culture to achieve an OD<sub>600</sub> of 0.1. The cultures were cultivated at 37 °C and 140 rounds per minute (rpm). After growing to an OD<sub>600</sub> of 0.6-0.8, HUHF expression was induced with 1 % L-arabinose. After induction the flasks were incubated at 28 °C and 140 rpm for six hours. Samples were taken hourly for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/73/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--SDS_PAGE_LK.pdf">(SDS-PAGE)</a>. | ||

Moreover, the samples were further purified. Therefore, the <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7e/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Ferritin_Purification_LK.pdf">protocol</a> of <a href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-CeBiTec/Attributions">Dr. Jon Marles Wright</a> has been applied. The samples were pelleted (13000 g, 1 min), the media was discarded and cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM tris pH 8, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 20 mM mannitol). Afterwards the cells were lysed by sonication, centrifuged (10000 g, 20min), heated to 80 °C for 10 minutes, put on ice for 10 minutes and centrifuged (10000 g, 10 min) again. Purified HUHF was located in the supernatant. | Moreover, the samples were further purified. Therefore, the <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/7e/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Ferritin_Purification_LK.pdf">protocol</a> of <a href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-CeBiTec/Attributions">Dr. Jon Marles Wright</a> has been applied. The samples were pelleted (13000 g, 1 min), the media was discarded and cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM tris pH 8, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 20 mM mannitol). Afterwards the cells were lysed by sonication, centrifuged (10000 g, 20min), heated to 80 °C for 10 minutes, put on ice for 10 minutes and centrifuged (10000 g, 10 min) again. Purified HUHF was located in the supernatant. | ||

| − | HUHF purified by this workflow was analyzed with a SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). Clearly visible bands have been recognizable at about 23 kDa, the expected hight for HUF. | + | HUHF purified by this workflow was analyzed with a <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/7/73/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--SDS_PAGE_LK.pdf">SDS-PAGE</a> (Fig. 1). Clearly visible bands have been recognizable at about 23 kDa, the expected hight for HUF. |

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | The SDS-PAGE of the purified HUHF showed intense bands at about 25 kDa, fitting to the theoretical molecular weight of HUHF of 24.087 kDa. To ensure the identity of the HUHF the band was cut out of the SDS-PAGE and prepared for matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation with time of flight analysis (MALDI-TOF) measurements. These show distinctive peaks for the HUHF. In addition, tandem mass spectrometry measurements show peptides specific for HUHF, thereby confirming HUHF expression as well as a successful purification workflow. Besides, measurements reveal that the HUHF has been expressed. | + | The SDS-PAGE of the purified HUHF showed intense bands at about 25 kDa, fitting to the theoretical molecular weight of HUHF of 24.087 kDa. To ensure the identity of the HUHF the band was cut out of the SDS-PAGE and prepared for matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation with time of flight analysis <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a3/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--MALDI_LK.pdf">(MALDI-TOF)</a> measurements. These show distinctive peaks for the HUHF. In addition, tandem mass spectrometry measurements show peptides specific for HUHF, thereby confirming HUHF expression as well as a successful purification workflow. Besides, measurements reveal that the HUHF has been expressed. |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/6/61/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Huf_MALDI-TOF_MO.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/6/61/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Huf_MALDI-TOF_MO.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 5:</b> Results of MALDI-TOF measurements. The peptide fragments show a recognizable pattern for the HUHF. | + | <b>Figure 5:</b> Results of <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a3/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--MALDI_LK.pdf">MALDI-TOF</a> measurements. The peptide fragments show a recognizable pattern for the HUHF. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | In Figure 5 the specific peptide fragments pattern of the HUHF can be seen. The samples were digested with trypsin prior MALDI-TOF. Per tandem mass spectrometry the peak with the m/z = 1345.649 was further examined (Figure 6).Thus, all results confirm that the measured sample contains HUHF. | + | In Figure 5 the specific peptide fragments pattern of the HUHF can be seen. The samples were digested with trypsin prior <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/a/a3/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--MALDI_LK.pdf">MALDI-TOF</a>. Per tandem mass spectrometry the peak with the m/z = 1345.649 was further examined (Figure 6).Thus, all results confirm that the measured sample contains HUHF. |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | The purified HUHF was used to produce gold and silver nanoparticles. Therefore, HUHF samples were prepared by removing the ferritin bound Fe<sup>3+</sup> ions. By applying the | + | The purified HUHF was used to produce gold and silver nanoparticles. Therefore, HUHF samples were prepared by removing the ferritin bound Fe<sup>3+</sup> ions. By applying the <a href="https://2018.igem.org/Wiki/images/6/65/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Remove_Iron_of_Ferritin_LK.pdff">iron removement protocol</a>, the Fe<sup>3+</sup> ions have been reduced to Fe<sup>2+</sup> ions. After the iron ions were removed, AuHCl<sub>4</sub> and AgNO<sub>3</sub> solutions were added as stated in the (<a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/35/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Produce_gold_in_Ferritin_LK.pdf">gold</a> and <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/f9/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--Silver_nanoparticle_synthesis_LK.pdf">silver</a>) protocols. The HUHF with the AuHCl<sub>4</sub> solution was incubated for 1.5 hours whereas the AgNO<sub>3</sub> solution was incubated for 18 hours while being illuminated by a 60 watts lamp. Afterwards the samples were centrifuged (10.000 g, 10 min) and further purified with a 100 kDa protein columns to remove denaturated HUHF. |

For demonstration of nanoparticle formation and determination of nanoparticle composition the samples were examined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). | For demonstration of nanoparticle formation and determination of nanoparticle composition the samples were examined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). | ||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/88/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--nanoparticles_result_LK.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/88/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--nanoparticles_result_LK.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 9:</b> The silver nanoparticles in our gold silver mutant ferritin <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2638999">(BBa_K2638999)</a> with a mean diameter of 8.2 nm were significant smaller than the nanoparticles of the wildtype human ferritin (BBa_K1189019) with a mean diameter of 531.8 nm. | + | <b>Figure 9:</b> The silver nanoparticles in our gold silver mutant ferritin <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2638999">(BBa_K2638999)</a> with a mean diameter of 8.2 nm were significant smaller than the nanoparticles of the wildtype human ferritin <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1189019">(BBa_K1189019)</a> with a mean diameter of 531.8 nm. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 206: | Line 206: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/87/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--jr--G1CAL_13and10nm.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/87/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--jr--G1CAL_13and10nm.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 10:</b> Automatic identification of | + | <b>Figure 10:</b> Automatic identification of two gold nanoparticles (13 and 10 nm) in the wildtype human ferritin sample <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1189019">(BBa_K1189019)</a>. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

<div class="article"> | <div class="article"> | ||

| − | Figure 10 shows two gold nanoparticles of 13 and 10 nm diameter that were produced by the wild type human ferritin sample <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1189019">(BBa_K1189019)</a>. They are slightly bigger than the expected size between 7 and 9 nm, and thus it | + | Figure 10 shows two gold nanoparticles of 13 and 10 nm diameter that were produced by the wild type human ferritin sample <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1189019">(BBa_K1189019)</a>. They are slightly bigger than the expected size between 7 and 9 nm, and thus it cannot be ensured that these particles are really produced by that enzyme. |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/68/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--jr--G1Bi_7and9nm.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/6/68/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--jr--G1Bi_7and9nm.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 11:</b> Automatic identification of | + | <b>Figure 11:</b> Automatic identification of two gold nanoparticles (7 and 9 nm) in the gold silver mutant ferritin sample <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2638999">(BBa_K2638999)</a>. These nanoparticles are approximately 30 % smaller than the nanoparticles produced by the wildtype ferritin. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | We could show that commercially available metal nanoparticles can be printed and melted to produce electronic circuits using temperatures as low as 350°C compared to the very high melting temperature of | + | We could show that commercially available metal nanoparticles can be printed and melted to produce electronic circuits using temperatures as low as 350°C compared to the very high melting temperature of 1083 °C required to melt bulk copper. To use the NP we produced ourself for the printing of conductive circuits would have required higher amounts of the synthesized nanoparticles and would also have required further purification steps. Through our talks to Benjamin Lehner working at NASA we knew already that proteins mixed with the nanoparticles would lead to no or very poor conductivity when trying to sinter them without further purification. Using our own nanoparticles would be the logical next step. |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/32/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--cg--PrintingElectronics.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/32/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--cg--PrintingElectronics.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 12: </b>Commercially available copper nanoparticles of | + | <b>Figure 12: </b>Commercially available copper nanoparticles of 40 nm size were prepared under a nitrogen (N<sub>2</sub>) gas atmosphere in a rather simple setup using a plastic bag with inlets for the hands. The NPs where enclosed by putting two microscope slides on top of each other to prevent oxygen from reaching the NP during the sintering process. The NPs between the glass slides were heated to 350 °C for 10 minutes. The heating step was repeated 3 times resulting in a solid surface with a measurable conductivity of around 0.9 Megaohm. Heating experiments at lower temperatures of only 250 °C showed no conductivity. Also heating to 350 °C under an oxygen atmosphere (no glas slide was put on top) only lead to structures which where not conductive. We also tried to solve the NP in water which was deoxidized by bubbling N<sub>2</sub> gas through it for 20 minutes. The NP solved in water and later dried under the N<sub>2</sub> atmosphere also showed no conductivity after treating them at 350 °C despite putting them between glass slides to avoid the oxidising effects of air. We suspect the NP reacted and oxidized when being treated with water which would result in a much higher melting temperature. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

Latest revision as of 18:24, 7 December 2018

Improve a Part

Short summary

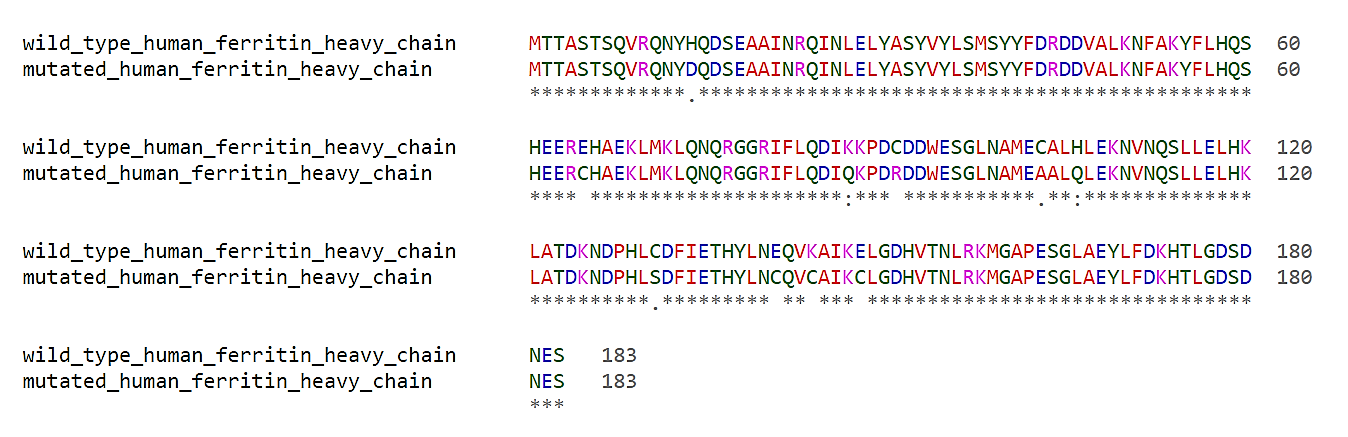

The Human Ferritin Heavy Chain (HUHF) BBa_K2638999 was successfully cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli DH5 alpha. After protein purification HUHF was used to produce gold and silver nanoparticles which was ensured by examinations with the Transmission Electron Microscope and Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). Thus, we improved BBa_K1189019 which is not able to form gold and silver nanoparticles.

The Calgary 2013 iGEM team used the human ferritin wildtype (BBa_K1189019) as reporter protein for a test strip. They expressed the human ferritin heavy and light chain heterologous using Escherichia coli. In the cells, the ferritin produced its characteristic iron core, which was colored with the help of fenton chemistry to produce the prussian blue iron complex. Beside the function as reporter, the team mentioned the capability of ferritin to produce nanoparticles from other metal ions.

Improved Human Ferritin: BBa_K2638999

Figure 7 shows a TEM image with 147 identified silver nanoparticles produced by the wild type human ferritin (BBa_K1189019). The particles are between 24.5 and 1597.8 nm in size with one very big particle with a size of 7272.3 nm, which seems to consist in many agglutinated silver nanoparticles. No particle was found in the expected size of about 8 nm.

Figure 8 shows a TEM image with 708 identified silver nanoparticles produced by the gold silver mutant ferritin sample (BBa_K2638999). The particles have a size between 1.8 and 34.8 nm. 120 of the silver nanoparticles (16.9 %) are exactly in the expected size of 7 to 9 nm which indicates that at least all of these particles are produced by our improved ferritin (BBa_K2638999).

The direct comparison of our new gold silver mutant ferritin (BBa_K2638999) and the old wild type human ferritin (BBa_K1189019) in figure 9 shows that our improved enzyme produces nearly five times more silver nanoparticles which are 98.5 % smaller than the silver nanoparticles produced by the wild type ferritin. This proves that the new ferritin enzyme is much more suitable for producing silver nanoparticles than the wild type version.

Figure 10 shows two gold nanoparticles of 13 and 10 nm diameter that were produced by the wild type human ferritin sample (BBa_K1189019). They are slightly bigger than the expected size between 7 and 9 nm, and thus it cannot be ensured that these particles are really produced by that enzyme.

Figure 11 shows two gold nanoparticles of 7 and 9 nm diameter that were produced by the gold silver mutant ferritin (BBa_K2638999). They are exactly in the expected size range, although it is difficult to draw reliable conclusions from this small size and number of particles.

Outlook

Molecular graphics and analyses performed with UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311.

Butts, C.A., Swift, J., Kang, S., Di Costanzo, L., Christianson, D.W., Saven, J.G., and Dmochowski, I.J. (2008).. Directing Noble Metal Ion Chemistry within a Designed Ferritin Protein † , ‡. Biochemistry 47: 12729–12739.

Castro, L., Blázquez, M.L., Muñoz, J., González, F., and Ballester, A. (2014).. Mechanism and Applications of Metal Nanoparticles Prepared by Bio-Mediated Process. Rev. Adv. Sci. Eng. 3.

Ensign, D., Young, M., and Douglas, T. (2004).. Photocatalytic synthesis of copper colloids from CuII by the ferrihydrite core of ferritin. Inorg. Chem. 43: 3441–3446.

Goujon, M., McWilliam, H., Li, W., Valentin, F., Squizzato, S., Paern, J., and Lopez, R. (2010).. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: W695-699.

Pettersen, E.F., Goddard, T.D., Huang, C.C., Couch, G.S., Greenblatt, D.M., Meng, E.C., and Ferrin, T.E. (2004).UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25: 1605–1612.

Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T.J., Karplus, K., Li, W., Lopez, R., McWilliam, H., Remmert, M., Söding, J., Thompson, J.D., and Higgins, D.G. (2011). Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7: 539.

Ummartyotin, S., Bunnak, N., Juntaro, J., Sain, M., and Manuspiya, H. (2012). . DSynthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles for printed electronics. /data/revues/16310748/v15i6/S1631074812000549/.

Wang, L., Hu, C., and Shao, L. (2017a).. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomedicine 12: 1227–1249.

Wang, Z., Gao, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, G., Niu, G., and Chen, X. (2017b).. Functional ferritin nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 11: 633–646.