Lillianparr (Talk | contribs) |

Lillianparr (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

<div style = 'padding-right: 14%; padding-left: 14%; text-indent: 50px;line-height: 25px;'> | <div style = 'padding-right: 14%; padding-left: 14%; text-indent: 50px;line-height: 25px;'> | ||

| − | + | Our first step was to validate that we could create constructs controlled by temperature. To that end, we created a simple inducible circuit containing a constitutively expressed ts-CI and an mScarlet-I-pdt under the control of R0051. By growing these circuits at 30C before inducing them at 37C, we were able to determine that the system was indeed controlled by temperature (Figure 2a). After confirming that activation of the system was controlled by temperature, we next tested to determine if reducing the temperature of the activated circuit would cause the production of mScarlet to cease. We found that the system does indeed stop production of mScarlet-I-pdt after the temperature is reduced, with a short delay due to the need for ts-CI production to initiate (Figure 2b). | |

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 00:38, 17 October 2018

Temperature Controlled Systems

Background

Due to the inherent limitations that we found to be present in our chemically induced IFFL system, a new method of gene expression control was required to test our decoding circuit. Ideally, this new method would be easy to turn on and off, modular enough to work in a wide variety of systems, and have the potential to be useful in applied projects. Based on these requirements, we selected a temperature-activated gene expression system. Temperature-based control presents several advantages over similar systems (e.g., optogenetics), namely in that temperature is easy to manipulate with nonspecialist lab equipment, and that temperature-based systems are well characterized and could potentially be useful for in vivo systems.

Design

We initially chose to design our temperature controlled IFFL using the temperature sensitive mutant of lambda CI (ts-CI) [1]. In this system, ts-CI acts as a repressor of the lambda phage promoter R0051 at low temperatures, but is irreversibly denatured by temperatures of 37C or higher. Our circuits based on this system contained a module that constitutively expressed ts-CI, as well as modules that placed the production of our reporter (mScarlet-pdt) and inhibitor (mf-Lon) under the control of R0051. When grown at 30C, ts-CI would be able to repress the production of both the reporter and inhibitor, but when the temperature was increased to 37C, ts-CI would be denatured, allowing for the production of both. If temperature were lowered again, more ts-CI would quickly be produced and the production of both the reporter and inhibitor would be repressed.

Figure 1: Schematic of BBa_K2680051

Initial Testing of ts-CI System

Our first step was to validate that we could create constructs controlled by temperature. To that end, we created a simple inducible circuit containing a constitutively expressed ts-CI and an mScarlet-I-pdt under the control of R0051. By growing these circuits at 30C before inducing them at 37C, we were able to determine that the system was indeed controlled by temperature (Figure 2a). After confirming that activation of the system was controlled by temperature, we next tested to determine if reducing the temperature of the activated circuit would cause the production of mScarlet to cease. We found that the system does indeed stop production of mScarlet-I-pdt after the temperature is reduced, with a short delay due to the need for ts-CI production to initiate (Figure 2b).

Figure 2: Relative fluorescence (fluorescence/max) measurements of the temperature activatable circuit BBa_K2680051 when grown at 30C and then activated by exposure to 37C for the entirety of the experiment (A) or transiently (B). Dots represent the geometric mean of 3 (B) or 6 (A) distinct biological replicates (colonies) and the blue shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean. The grey shaded region in (B) represents the period in which the temperature was 37C. Normalized fluorescence (relative to max) was calculated by dividing each colony relative to it's maximal expression.

Next, we designed a separate temperature controlled system (BBa_K2680050) that expressed mf-Lon, which we hoped to combine with K860052 to form a complete IFFL. However, while cells co-transformed with both of these parts grew fine at 29C, when the IFFL was turned on by heating to 37C, no change in fluorescence values was apparent. Upon inspection of the optical density values, the reason became clear. Upon activation of the IFFL an immediate drop in cell density occurred, indicating that the constructs were toxic to the cells (Figure 3a). This was not overly surprising, as previous teams have reported that high expression of mf-Lon has a cytotoxic effect on E. coli. Given that the promoter (R0051) driving the expression of mf-Lon is phage derived and has extremely strong expression, it is reasonable to believe that an overly high expression of mf-Lon led to this result. Next, we determined that the expression of mf-Lon from our construct actually led to cell death and did not merely inhibit growth (Figure 3b).

Figure 3: Optical density (absorbance) measurements of the temperature activatable circuit BBa_K2680051 on psb1C3 + BBa_K2680050 psb3K3 when grown at 30C and then activated by exposure to 37C for the entirety of the experiment (A) or transiently (B). Dots represent the geometric mean of 3 (B) distinct biological replicates (colonies) and the blue shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean. The grey shaded region represents the period in which the temperature was 37C.

Refinement of ts-CI System

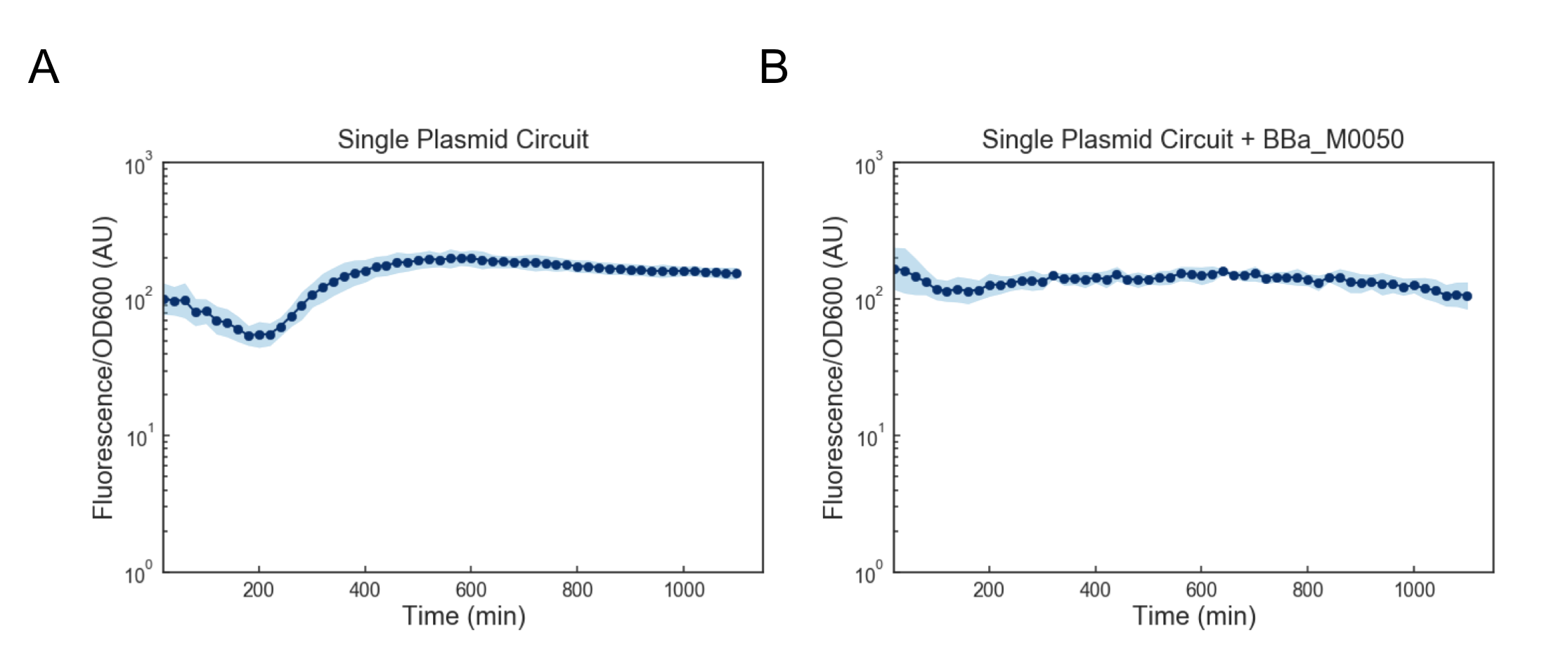

We first attempted to get around this issue by using a lower temperature of 35C to activate the cells, but found that this still lead to cell death (data not shown). Based on these results, we reasoned that we might want to reduce the expression of mf-Lon as well as the expression of mScarlet-I-pdt, as in conjunction they appeared to strongly cytotoxic. We reasoned that one way to resolve this would be to express all transcriptional units together on a single plasmid on the low-medium copy backbone psb3K3. However, when we tested this single plasmid construct we found that while cell growth was normal, there was no appreciable gain in fluorescence upon induction (Figure 4a). As this construct was sequenced confirmed (see WM18_016 3K3 in sequencing on Data and Methods), we deemed it likely that there was simply too much mf-Lon expressed relative to mScarlet-I-pdt. This matches with previous characterization where the amount of ratio of mScarlet-I to mf-Lon needed to be far higher than what our construct would likely achieve in order to observe a pulse. We reasoned that one potential solution would be to add a strong ssrA tag (BBa_M0050 onto mf-Lon in order to increase its endogenous degradation rate, which would serve to lower its expression. However, we found that the single plasmid circuit with the ssrA performed similarly to the single plasmid circuit without the ssrA tag (Figure 4b).

Figure 4: Fluorescence/OD600 measurements of a ts-CI based single plasmid circuit containing mf-Lon with (A) and without (B) BBa_M0050. Constructs were grown at 30C and then activated by exposure to 37C at t=0 through the rest of the experiment. Dots represent the geometric mean of 3 distinct biological replicates (colonies) and the blue shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean.

After determining that these specific single plasmid IFFLs did not have appropriate parameters, we next investigated whether any single plasmid circuit made up of our existing parts was capable of generating the characteristic pulse of an appropriately tuned IFFL. Utilizing 3G Assembly to generate huge numbers of different single plasmid circuits in a single reaction, we were ultimately able to determine that no combination of our current parts would lead to a functional single plasmid IFFL circuit on psb3K3 (see the parallel 3G Assembly page for more information). While this result meant we now had to change which heat sensitive system we would use for our decoder, it ultimately saved us many weeks of experiments. Hopefully, this technique will also enable future teams to perform similar experiments to evaluate potential configurations of their circuits.

TlpA Based System

The system that we decided upon was based on tlpA39 (BBa_K2680279), a version of the tlpA repressor found in Salmonella typhimurium, which was engineered by Piraner, et al to have an activation temperature of 39C [2]. We chose tlpA39 as it was mechanistically similar to ts-CI, but possessed several advantages compared to ts-CI. These advantages included that our cells would not have to be grown at special temperatures during cloning, as well as that this system has two different promoters, which differ by over 200 fold, which would give us a larger range of parameters which we could use to design our IFFL circuit.

Utilizing 3G assembly, we then design a wide variety of heat inducible circuits, with both the ptlpA (BBa_K2680123), and the ~200 fold weaker ptlpAR promoters (BBa_K2680123) as well as various combinations of different mScarlet-pdts and mf-Lon with and without M0050. After testing however, we found that none of the combinations of the new parts produced the characteristic pulse of an IFFL (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Normalized to max fluorescence of various non pulsing constructs. Cells were grown at 30C then activated at 39C for the remainder of the experiment. Dots represent the geometric mean of 3 distinct biological replicates (colonies) and the blue shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean.

We considered that there might be issues with one or more of the components of our constructs. So we tested some of our mScarlet-I pdt constructs and determined that in fact the degradation tags do perform appropriately in the presence of mf-Lon, with the stronger degradation tags having lower fluorescence compared to the weaker degradation tags, which were weaker than the untagged control (Figure 6a). Further, we found that the calculated degradation rates were in line with our expectations, with the tags being in order of expected strength based on Cameron and Collins [3] (Figure 6b).

Figure 6: (A). Time course measurements of various mScarlet-I pdt constructs combined with an mf-Lon construct. Values are normalized relative to the untagged control. Each dot represents the geometric mean of 3 biological replicates and the shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean. (B). Relative degradation rates calculated with respect to the untagged control. Each dot represents a single biological replicate at maximal expression, and bars represent the geometric mean of replicates. Tags are arranged from weakest to strongest, left to right.

We next tested whether our heat inducible mf-Lon constructs were working by combining it with the well characterized ATc inducible mScarlet construct K2333428. Using this we were able to determine that our mf-Lon constructs were indeed functional, and that there was little to no difference in degradation rate between mf-Lon (K2680060) and mf-Lon-M0050 (K2680061) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Comparison of degradation of pdt#3 tagged mScarlet-I after activation of mf-Lon constructs. Each dot represents the ratio of the geometric means of at least 10,000 single cell measurements of the pre/post activation of mf-Lon. Lines represent the geometric mean of the 3 biological replicates.

Concurrently with these tests, we were also working on integrating constructs onto the genome using pOSIP[4]. We made a strains that expressed either mf-Lon or mf-Lon-M0050 under the control of the ptlpA and ptlpAR, as well as a mf-Lon under the control of the R0051 promoter. We confirmed their integration as indicated in the pOSIP protocol, and then functionally tested them with the ATc inducible mScarlet-I-pdt K2333428 (see above section). When we transformed K2333428 into the cells containing integrated mf-Lon constructs, we found that simultaneous activation of mScarlet-I-pdt (via ATc) and mf-Lon (via temperature change) generated the characteristic IFFL pulse (Figure 8). However, when we attempted to use our temperature controlled mScarlet-pdt parts in the integrated cells, no pulse was observed (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Measurement of ATc inducible mScarlet-I-pdt with various integrated constructs. Each dot represents the geometric mean of 3 biological replicates and the shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean.

Figure 9: Measurement of ptlpA controlled mScarlet-I pdt#3 along with a ptlpA controlled mf-Lon with (A) and without (B) M0050 on psb3k3. Values are normalized relative to maximal expression. Each dot represents the geometric mean of 3 biological replicates and the shaded region represents one geometric standard deviation above and below the mean.

References

[1] Nandan Kumar Jana, Siddhartha Roy, Bhabatarak Bhattacharyya, Nitai Chandra Mandal; Amino acid changes in the repressor of bacteriophage lambda due to temperature-sensitive mutations in its cI gene and the structure of a highly temperature-sensitive mutant repressor, Protein Engineering, Design and Selection, Volume 12, Issue 3, 1 March 1999, Pages 225–233, https://doi.org/10.1093/protein/12.3.225

[2] Piraner, D. I., Abedi, M. H., Moser, B. A., Lee-Gosselin, A., & Shapiro, M. G. (2016). Tunable thermal bioswitches for in vivo control of microbial therapeutics. Nature Chemical Biology, 13(1), 75-80. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2233

[3] D Ewen Cameron and James J Collins. Tunable protein degradation in bacteria. Nature biotechnology, 32(12):1276–1281, 20

[4] One-Step Cloning and Chromosomal Integration of DNA

François St-Pierre, Lun Cui, David G. Priest, Drew Endy, Ian B. Dodd, and Keith E. Shearwin

ACS Synthetic Biology 2013 2 (9), 537-541

DOI: 10.1021/sb400021j