| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | The Calgary 2013 iGEM team used the human ferritin | + | The Calgary 2013 iGEM team used the human ferritin wildtype (<a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1189019">BBa_K1189019</a>) as reporter protein for a test strip. They expressed the human ferritin heavy and light chain heterologous using <i>Escherichia coli</i>. In the cells, the ferritin produced its characteristic iron core, which was colored with the help of fenton chemistry to produce the prussian blue iron complex. Beside the function as reporter, the team mentioned the capability of ferritin to produce nanoparticles from other metal ions. |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | The | + | The wildtype ferritin has reactive amino acids on the outside and inside of the protein shell, causing nanoparticle synthesis at both surfaces. An optimization of the wildtype human ferritin towards a nanoparticle syntheses mainly in the interior can therefore favor a unified production of different nanoparticles (Butts et al., 2008). |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8c/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--ferritin_alignment.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/8c/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--ferritin_alignment.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

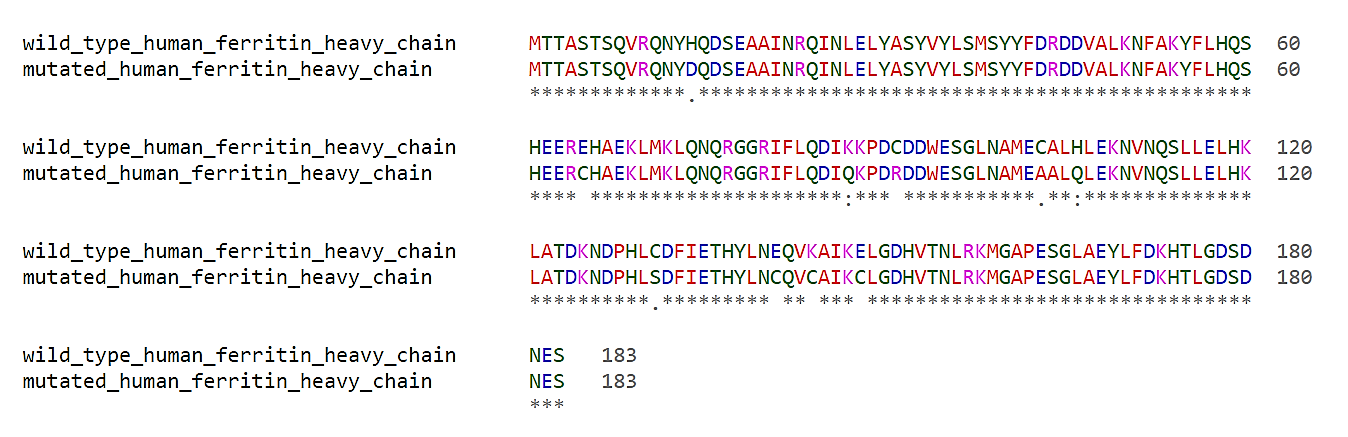

| − | <b>Figure 2:</b> Alignment of the protein sequences of the | + | <b>Figure 2:</b> Alignment of the protein sequences of the wildtype and the mutated human ferritin heavy chain. The Alignment was produced with Clustal Omega (Goujon et al., 2010, Sievers et al., 2011). |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

<article> | <article> | ||

| − | In Figure 2 the amino acid sequence alignment of the | + | In Figure 2 the amino acid sequence alignment of the wildtype human ferritin and the mutated human ferritin is shown. The exterior residues C91R, C103A, C131S, H14D and H106Q, and the interior residues E65C, E141C, E148C, K87Q and K144C were mutated. The mutations have no influence on the structure of the ferritin as shown in Figure 3. |

</article> | </article> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/03/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--ferritin_comparison_vk.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/0/03/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--ferritin_comparison_vk.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 3:</b> Protein structures of the | + | <b>Figure 3:</b> Protein structures of the wildtype human ferritin (<b>A</b>, RCSB ID 4oYN) and the mutated human ferritin (<b>B</b>, RCSB ID 3ES3). Despite the mutations of ten amino acids the ferritin retains its shape. The protein structeres were generated with Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/39/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--BBa_K1189019_LK.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/39/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--BBa_K1189019_LK.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 4:</b>Automatic identification of 147 silver nanoparticles in the | + | <b>Figure 4:</b>Automatic identification of 147 silver nanoparticles in the wildtype human ferritin sample (BBa_K1189019). |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

<img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/88/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--nanoparticles_result_LK.png"> | <img class="figure hundred" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/8/88/T--Bielefeld-CeBiTec--nanoparticles_result_LK.png"> | ||

<figcaption> | <figcaption> | ||

| − | <b>Figure 6:</b> The silver nanoparticles in our gold silver mutant ferritin (BBa_K2638999) with a mean diameter of 8.2 nm were significant smaller than the nanoparticles of the | + | <b>Figure 6:</b> The silver nanoparticles in our gold silver mutant ferritin (BBa_K2638999) with a mean diameter of 8.2 nm were significant smaller than the nanoparticles of the wildtype human ferritin (BBa_K1189019) with a mean diameter of 531.8 nm. |

</figcaption> | </figcaption> | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

Revision as of 23:58, 17 October 2018

Improve a Part

Original Part: BBa_K1189019

Improved Human Ferritin: BBa_K2638999

Outlook

Molecular graphics and analyses performed with UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311.

Butts, C.A., Swift, J., Kang, S., Di Costanzo, L., Christianson, D.W., Saven, J.G., and Dmochowski, I.J. (2008).. Directing Noble Metal Ion Chemistry within a Designed Ferritin Protein † , ‡. Biochemistry 47: 12729–12739.

Castro, L., Blázquez, M.L., Muñoz, J., González, F., and Ballester, A. (2014).. Mechanism and Applications of Metal Nanoparticles Prepared by Bio-Mediated Process. Rev. Adv. Sci. Eng. 3.

Ensign, D., Young, M., and Douglas, T. (2004).. Photocatalytic synthesis of copper colloids from CuII by the ferrihydrite core of ferritin. Inorg. Chem. 43: 3441–3446.

Goujon, M., McWilliam, H., Li, W., Valentin, F., Squizzato, S., Paern, J., and Lopez, R. (2010).. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: W695-699.

Pettersen, E.F., Goddard, T.D., Huang, C.C., Couch, G.S., Greenblatt, D.M., Meng, E.C., and Ferrin, T.E. (2004).UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25: 1605–1612.

Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T.J., Karplus, K., Li, W., Lopez, R., McWilliam, H., Remmert, M., Söding, J., Thompson, J.D., and Higgins, D.G. (2011). Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7: 539.

Ummartyotin, S., Bunnak, N., Juntaro, J., Sain, M., and Manuspiya, H. (2012). . DSynthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles for printed electronics. /data/revues/16310748/v15i6/S1631074812000549/.

Wang, L., Hu, C., and Shao, L. (2017a).. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomedicine 12: 1227–1249.

Wang, Z., Gao, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, G., Niu, G., and Chen, X. (2017b).. Functional ferritin nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 11: 633–646.