Introducton

After the exceptional performance of ProteinGAN which was able successfully generate amino acid sequences only using a network that learnt various rules and patterns about protein molecules by itself, we have decided to extend it.

This time we focused on the generation of enzymes. As already described earlier, one of the main drawbacks of enzymes is that for many important chemical reactions efficient enzymes have not yet been discovered or engineered.

We have built upon ProteinGAN which we extended by incorporating additional information of chemical reactions each enzyme catalyses. It required a partial revamp of ProteinGAN architecture and the collection, preparation and standardization of chemical reaction library which we have gathered from various open sources.

The goal of this new network is to not only learn the rules of protein sequences, but also to learn the connection betweenenzyme sequences and reactions they catalyze.

In other words, we want to see if our new network can generate enzymes when given a specific reaction. We call it the ReactionGAN.

Building the reaction and protein sequence library

In order to train ReactionGAN, in addition to the sequences which we have collected for ProteinGAN, we have gathered a dataset from ExPASy (Gasteiger et al. 2003)which contained catalytic information about each class. From downloaded dataset, we extracted reactions described in words for each class. Reactions then were converted to SMILES format using PubChem (Kim et al. 2016) and MetaCyc (Caspi et al. 2016) Compound databases in order to have a standardized way of presenting reaction to the neural network. As a consequence, SMILES format allows us to input any reaction, regardless whether it was in the training set or not. To simplify the search space, we constrained dataset to have only 23 most common SMILES symbols. Furthermore, to reduce the complexity, we only selected reactions that have maximum two substrates and two products.

In regards to protein sequences, our aim was to find at least 200 sequences for every class of enzymes. The initial ProteinGAN dataset downloaded from UniProtKB is relatively sparse for our purpose, therefore we decided to upsample using the NCBI RefSeq non-redundant protein database (nrDB). We used MMseqs2 (Steinegger et al. 2017) to cluster our selected enzyme database using 90% sequence identity threshold and over 80% sequence coverage, which resulted in a total of 77,686 representative sequences. This step was taken to reduce the redundancy of sequence database which was used as a query database for the MMseqs2 search workflow. To upsample, we searched our clustered database against nrDB using these parameters: 30% sequence identity threshold, 80% sequence coverage, 3 sensitivity level; and afterwards extracted 98% identity representatives. The resulting database increased several-fold (compared to 130,201 initial database 98% sequence identity representatives) totalling up to 412,769 sequences, which were used to assemble training and test sets for ReactionGAN. All classes with more than 200 associated sequences were selected as a training set, resulting in 138,902 sequences and over 50 classes. All the remaining classes were collected to serve as a test set. As a result, our dataset in total contained over 100 unique reactions, and over 200 unique reactions if protein sequence length is increased to 512 amino acids.

We used CLANS (Frickey and Lupas, 2004) with default parameters to explore the whole enzyme sequence space that we have generated. To ensure that the space is not too crowded and still possible to visualize, we are only showing the representatives of 25% sequence identity clusters:

Figure 1. Visualized enzyme sequence space. Sequences are represented as vertices. Distances between clusters represent sequence similarities. BLAST High-scoring pairs are represented by edges, showing local sequence similarities shared by sequences.

We can clearly see that enzyme sequences cluster together if they belong to a certain class. Also, some of the classes seem to merge in the same cluster, reflecting that these enzymes are multifunctional, or simply more related from evolutionary perspective than other classes nearby.

ReactionGAN

ReactionGAN is a conditional generative adversarial network architecture (Mirza and Osindero, 2014) that is capable of generating de novo proteins for a given reaction. Once trained, you can use it by simply providing a list of reactions. The output will contain corresponding generated sequences.

The key difference between ReactionGAN and ProteinGAN is that ReactionGAN is a conditional GAN which takes reaction catalyzed by the enzyme as an s input in order to generate a protein that belongs to the same enzyme class. Whereas the discriminator uses enzyme class information to not only distinguish whether the sequence is generated or real, but also checks if generated sequence belongs to given enzyme class (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. High-level design of ReactionGAN

Generating the sequences

ReactionGAN with a two reaction

ReactionGAN, which now takes into account enzymatic reaction, was trained in order for it to grasp how each sequence is related to chemical reaction the enzyme may catalyze. First, we chose only two reactions:

Once training has been completed, we used the same reactions as an input to ReactionGAN to generate sequences. This is an example of one sequence it has produced:

MIPGEYQIQNTEIKINAGRATQTINVANTG0RPIHVGS0YHFYEVNSAI0FDREAARGFRLNVAAGTAVRFEPGQTREVQLVEYAGKHDVYGFRGDVMGSIEQ (class:3.5.1.5)

Figure 3. Generated class 3.5.1.5 sequence and the whole class consensus sequence alignment. Matching amino acids highlighted in red, synonymous - in yellow. Class consensus was generated using EMBOSS cons tool. “X” symbols represent positions where consensus could not be called. Alignment figures generated using ESPript 3.0 (Robert and Gouet, 2014).

Just like in the ProteinGAN section, we could not find this exact sequence in the dataset. In turn, it is a unique representation of a specific enzyme, that may have the ability to catalyze the given reaction. What is more, the most similar proteins received from running BLAST were from the same class we were generating for, and it does align well to our consensus for similar proteins in the same class! This gave us confidence to apply ReactionGAN to more reactions.

ReactionGAN with multiple reactions

For final test we used 51 different reactions which included around 140k unique enzyme sequences. We have left the network to train for 80 hours (on Google cloud instance with NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU (16GB)). Entire network contained ~18M trainable parameters. Hyper-paramaters were selected the same as for ProteinGAN. To test the training we have randomly chosen one reaction from the dataset:

and used it as an input to the ReactionGAN. This is an example of a sequence which has returned by the generator:

Figure 4. Generated class 3.5.1.19 sequence and the whole class consensus sequence alignment. Coloring as in Figure 3.

To verify whether the ReactionGAN is capable of distinguish various reactions, the network was given given the following reactions as well:

This generated the following sequences:

Figure 5. Generated class 3.6.1.65 sequence and the whole class consensus sequence alignment. Coloring as in Figure 3.

Figure 6. Generated class 3.5.1.105 sequence and the whole class consensus sequence alignment. Coloring as in Figure 3.

As before, we could not find the exact sequence in the dataset we have used to train the ReactionGAN - it has produced a unique sequence.

- MTEWELIDESETVGLALKHRGATYTSAESRTGGWLAKAITDISGSSAWFERGFVTYSNEAKRLLVAVNDQLTAQRGLVNEAGVVMEGVGAKDASNADVALSGAGVAGLDGSTAEKPVGTVLFAFADVRGQPQNRRESFSGDRDSVRGQATLAALTTAFKDFLSKTEILLN (class:3.5.1.42)

- MTIRRLVLLRSGQDDVNVPAREQPDQDTVISDLPRSTAVRAAEVKPKQEALVVINNDLREAVEDALHIATHNGIPIRIDIRVNEGHLLDWQGLDHHEVDASAPAARLALRDNATWTIQVGESRVDVAGRNVVVVLELVKAMGDHACASNDMFIVRVAGNALLAALMPGALLGDVLKRNGSNASVRGGRAILLGPPGEGADTGLRLIRRLGVVAVGDYGASTVVF (class:3.1.3.85)

- MKIFTPAPFQFEGGKRAVLVLHGFTGNSADVRMLGRWLERRAKTCHGAQYKGHGVPPEELVHTGPAIWWKDVMDGYDFLKDKPYEEIAVSGLSLGGVFSLKLGYTVHVKGIVKLCAPMYIKSEEEMYEGVLEYAREYKRREGKQAEYIEQELAEFIKTPMETLKALQDLIHDVRAHVDMIYGPTFVVQARHDHMINNESANIIYDAVENETKTQKWYEESGFVITLDKEREQLNEDVYEILEQLDWHE (class:3.1.1.1)

- MGREIERKFLVTGNAWPAPGDGGVFRQGYLASADGNTVRVRIEGNKGWLTIKGANVGLTRGEMEYPVPLEDADEILDGICERPLIEKYRYRFESAGLIWEVDEFMGANAGLVVAEIELPSEDQVFEKPDWIGREVNEDLRYYNSNLVRFPFSHW (class:3.6.1.3)

- MELTPREKDKLLLFTAALIAERRKARGLKLNYPESIAVISSAIMEGAREGKTVASLMEAGRTVLTRDQVMEGVPEAIPDIQVEATFPDGNKLVTVHNPIV (class:3.5.1.5)

- MIWKRDVTIEELNELSDGNMVGLLDIRFTQVGDDTLEATMPVDSRTKQPFGLLHGGASVVIAENFGSVAGYLCQEGEQKVVGLEVNANKIRSARDGRVRGVCKAIHMGRRHQVWTIAIFDEHGRFCAQSRLTTAVI (class:3.1.2.28)

BLAST results confirmed that sequences our network have generated were the most similar to the sequences that belong corresponding classes:

Table 1. Top results from BLAST for 3 sequences

As before we looked at similarities between generated and real sequences, and results were impressive. Without seeing any of proteins, the generator created a unique amino acid sequence that resembles a lot sequences from the same enzyme class.

This allows us to believe that ReactionGAN learnt differences between the enzyme sequences based on their catalyzed reaction!

ReactionGAN with unseen reactions

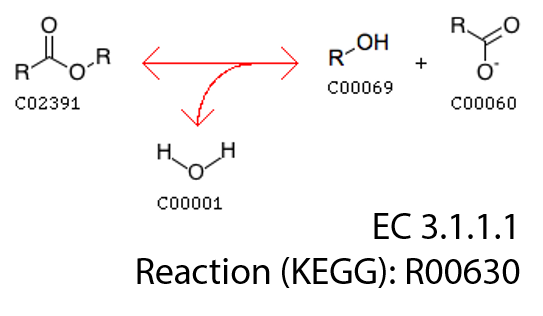

As we can see, class EC3.1.1.1 classifies sequences catalyzing a basic enzymatic reaction:

We had 762 of these sequences in our training set.

A more concrete enzyme class would be triacylglycerol acylhydrolases, where at least the alcohol part of the substrate is fixed. This class was in our test set and the corresponding reaction was never shown to our ReactionGAN. With this in mind, we aimed to test whether ReactionGAN can generate an unseen before sequence for a reaction which was not previously introduced.

After BLAST searching against UniProtKB database for class EC3.1.1.3, we have found considerable hits:

Table 2. Top three hits from BLAST for a generated class 3.1.1.3 sequence

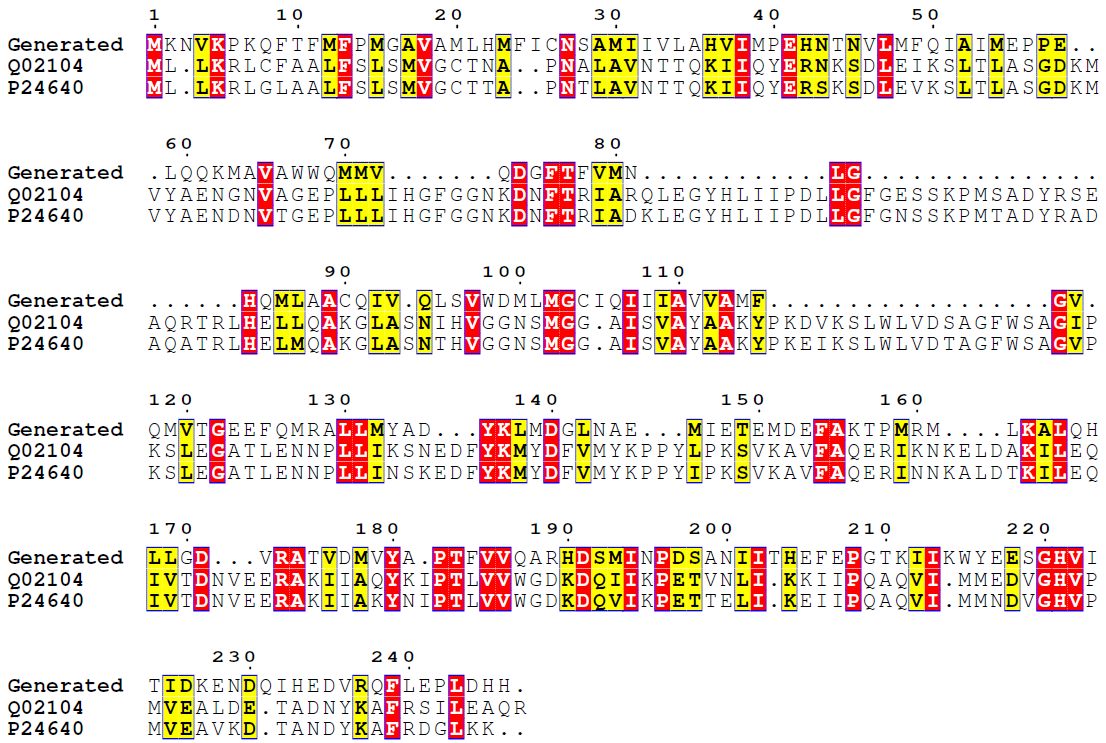

From these results it can be seen that a certain sequence motif is shared between the two classes (Query/subject start-end), which is at similar positions for the two first sequence hits as in the generated sequence. To examine further, we have generated a multiple sequence alignment with two best hits:

Figure 6.Generated unseen class 3.1.1.3 sequence and two top BLAST hits sequence alignment. Coloring as in Figure 3.

Clearly, our ReactionGAN generated at least one sequence somewhat similar to sequences from another class of enzymes! Of course, certain domains might be conserved throughout different classes, however this result proves that ReactionGAN can actually navigate the vast protein sequence spacegiven only a reaction and output an enzyme which resembles of real enzymes.

Realistically, these results could not be hoped for every enzyme class, possibly, due to a very limited amount of reactions in the training set (51). Longer training time, increased maximum sequence length to 512 together with the list of reactions to over a 100 could certainly lead to more concrete conclusions. After seeing these results, we will for certain keep improving this neural network and looking for even more high quality data to implement.

Conclusions

The ReactionGAN demonstrated ability to generate corresponding enzymes only by using reaction without ever seeing any proteins. Our implementation of GANs has successfully learned not only how an enzyme’s sequences should look like, but also recognised how reactions they catalyse affect the sequence. After the immense amount of training, they could predict the right sequences for reactions of interest.

We hope that we have showed the great potential of Generative Adversarial Networks in Synthetic Biology and general research.

Building ReactionGAN network has ultimately motivated us to create CAT-Seq: Catalytic Activity Sequencing. We think that the ReactionGAN and CAT-Seq will complement each other. First, the CAT-Seq system can be used to generate immense amount of activity and sequence relationship data for generative networks to utilise in order to perform even better. Secondly, as ReactionGAN outputs millions of unique sequences for which the CAT-Seq is the only viable solution to assign activity value in an ultra-high speed.

We believe that CAT-Seq together with AI tools such as ReactionGAN will immensely accelerate the creation of synthetic biological parts and systems.

Deeper look

Training process

The training process is nearly identical to ProteinGAN apart from two key differences. The first extension of ReactionGAN is that the generator receives not only random numbers drawn from random Gaussian distribution, but also reactions. These reactions are compressed into smaller representation using so-called encoder. A reaction is the starting point from which a protein is being generated. Random numbers as before serve as an input which forces to produce different sequence every time.

The second difference is that the discriminator takes into account whether a protein belongs to a given class. To achieve this, all sequences are passed along with corresponding enzyme class identifier. With this additional information, the discriminator is able to penalize the generator not only for generating unrealistic examples, but also for producing sequences that appear to belong to different enzyme class.

Remaining steps are identical to the ones described in ProteinGAN.

Architecture details

ReactionGAN network is built on top of ProteinGAN with few extensions that are described below.

Encoder

In addition to ProteinGAN architecture, residual blocks were used to build the encoder (Figure 7) to compress reactions in to a smaller representation. Dimensions of reactions are reduced by applied convolutional filters with stride 2. Compressed reaction and random noise is simply concatenated before passing to next layers of the generator. The rest of the generator network remained unchanged.

Figure 7. High level architecture of Generator

Projection Discriminator

In order for the discriminator to cope with multiple classes, we have implemented a newly developed technique called Project Discriminator (Miyato and Koyama, 2018). This approach has been successfully used in recent implementations of GANs that showed astonishing results in image generation (Brock, Donahue and Simonyan, 2018). The idea of projection discriminator is relatively simple. Each class variable is embedded (turned in to vector) of the size of the last layer in the discriminator which then is combined with the output of last layer and finally added to the final score (see Figure 8). By doing so, the discriminator uses the embedding to highlight features that differentiates classes from each other.

Figure 8. High level architecture of Generator

ProteinGAN and ReactionGAN can be executed using command line. In order to run the script you will need Python 3.6 and Tensorflow library (full list of required packages can be found here https://github.com/donatasrep/igem). For training it is recommended to have use CUDA-enabled GPU (more details: https://www.tensorflow.org/install/gpu). In order to train a neural network on new data, you will need to provide a path to the directory where all sequences are stored. Selected sequences for training should be stored in file called train.tfrecords (it is important to have data in tfrecords format to achieve maximum throughput time). Directory has to contain a properties file which includes metadata information about sequences (please see an example in the github). A full list of configurable parameters can be displayed by running:

python generate --helpfull In order to train ReactionGAN along the sequences you should also provide enzyme reactions in SMILES format as well as enzyme class identifier. The only difference is that you can to pass different architecture, see an example below: python -m train_gan --batch_size 128 --steps 100000 --dataset “protein\gan\sample” [An example command for ProteinGAN] python -m train_gan --batch_size 128 --steps 100000 --dataset “protein\cgan\sample” --architecture conditional An example command for ReactionGAN During the training application automatically saves weights of the neural network so that it could be restored and used for generation. It is important to remember that you can have multiple versions for network, hence, generation script should be executed with same parameters as for training. For example:

python -m generate --batch_size 128 --steps 100000 --dataset “protein\gan\sample” An example command for ProteinGAN python -m generate --batch_size 128 --steps 100000 --dataset “protein\cgan\sample” --architecture conditional An example command for ReactionGAN The output should look like this:Setting up from own GANs

Training

Generating new sequences

Brock, A., Donahue, J. and Simonyan, K. (2018). Large Scale GAN Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. [online] Arxiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.11096 [Accessed 14 Oct. 2018].

Caspi, R., Billington, R., Ferrer, L., Foerster, H., Fulcher, C. A., Keseler, I. M., … Karp, P. D. (2016). The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(D1), D471–D480. http://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1164

Frickey, T., & Lupas, A. (2004). CLANS: A Java application for visualizing protein families based on pairwise similarity. Bioinformatics, 20(18), 3702–3704. http://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bth444

Gasteiger, E., Gattiker, A., Hoogland, C., Ivanyi, I., Appel, R. D., & Bairoch, A. (2003). ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(13), 3784–3788. http://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg563

Kim, S., Thiessen, P. A., Bolton, E. E., Chen, J., Fu, G., Gindulyte, A., … Bryant, S. H. (2016). PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(D1), D1202–D1213. http://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv951

Mirza, M. and Osindero, S. (2014). Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. [online] Arxiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.1784 [Accessed 17 Oct. 2018].

Miyato, T. and Koyama, M. (2018). cGANs with Projection Discriminator. [online] Arxiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.05637 [Accessed 16 Oct. 2018].

Shi, W., Caballero, J., Huszar, F., Totz, J., Aitken, A., Bishop, R., Rueckert, D. and Wang, Z. (2016). Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network. [online] Arxiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05158 [Accessed 16 Oct. 2018].

Robert, X., & Gouet, P. (2014). Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(W1), 320–324. http://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku316

Steinegger, M., & Söding, J. (2017). MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nature Biotechnology, 1–3. http://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3988