Careful planning puts you ahead in the long run; hurry and scurry puts you further behind

-- King Solomon

All these approaches require intense theoretical groundwork. Many hours have to be spent with screening literature, summarizing the current state of knowledge and finally, developing own ideas. Constructs have to be designed and experiments have to be planned.

All this preliminary work has to be completed before the lab work can be truly started. In addition to our initial theoretical work, we routinely iterated the steps: designing, building, testing and learning throughout the whole project.

On this page, we want to provide you the theoretical groundwork that we did to design our projects. We want to demonstrate that we followed Synbio design principles and conceived our project based on the current state of knowledge.

A major goal of our project was to create a collection of characterized parts for use in V. natriegens to provide other iGEM teams, as well as the whole scientific community a toolbox for the rational design of metabolic pathways, genetic circuits or any other DNA construct.

Our toolbox was initially conceived for being used in V. natriegens. However, while designing the Marburg Collection, we realized that a toolbox with maximum flexibility can easily be used in more than one bacterial species. Because alternative bacterial chassis, apart from E. coli, are gaining increasing importance

(Kim et al. 2016. )

, a toolbox that is compatible with more than one bacterial species enables scientists to work with organisms that have the exact properties needed for specific applications. Our vision is to establish the Marburg Collection as the first broad-host range golden-gate-based cloning toolbox.

De novo assembly of LVL1 plasmids from eight basic parts.

All basic parts like promoters or resistance parts are stored in LVL0 plasmids. The assembly of a plasmid comprising a single transcription unit is done by assembling at least eight parts resulting in one LVL1 plasmid. One to five LVL1 plasmids can then be used for a subsequent round of assembly to obtain a multigene LVL2 plasmid which could already harbor a full synthetic metabolic pathway consisting of up to five enzymes. Our toolbox even allows more rounds of assembly, each combining up to five constructs of the previous level. This enormous cloning capacity results theoretically in an infinite number of transcription units that can be assembled in a small amount of time.

Basic building blocks like promoters or terminators are stored in level 0 plasmids. Parts from each category of our collection can be chosen to built level 1 plasmids harboring a single transcription unit. Up to five transcription units can be assembled into a level 2 plasmid.

All LVL0 parts have to be stored in plasmids to allow for amplification and long term storage. To create new LVL0 parts, a PCR product or annealed oligos are cloned into a part entry vector. This vector harbours the resistance and ori that are required for selection and propagation. Furthermore, part entry vectors can be designed in a way that they contain a dropout. This dropout can be a transcription unit for a marker that generates a visible output. The first golden-gate-based toolbox MoClo (Weber et al. 2011) used a LacZ alpha transcription unit which can be used for blue white screening in many E. coli cloning strains. This concept was also adapted by iGEMs PhytoBrick system. During the cloning of LVL0 parts, this dropout is replaced by the desired part. When the cloning reaction is transformed into a suitable E. coli strain and the cells are plated on agar plates with supplemented IPTG and X-Gal. Colonies transformed with the religated entry plasmid appear blue while white colonies most probably contain the correctly assembled plasmid. The LVL0 part entry vector in iGEMs PhytoBrick system (BBa_P10500) has been designed as described and can be used for blue white screening.

We appreciate the approach of using part entry plasmids with dropouts but, for two reasons, we think that LacZ is not an optimal reporter. First, blue white screening requires the two expensive chemicals IPTG and X-Gal which have to be added to the agar plates. Second, blue white screening is restricted to E.coli strains with an incomplete lac operon that is complemented by the LacZ alpha fragment that is expressed from the plasmid (Langley et al. 1975). Consequently blue white screening is not compatible with a V. natriegens wild type strain (Link zu Improvement Page).

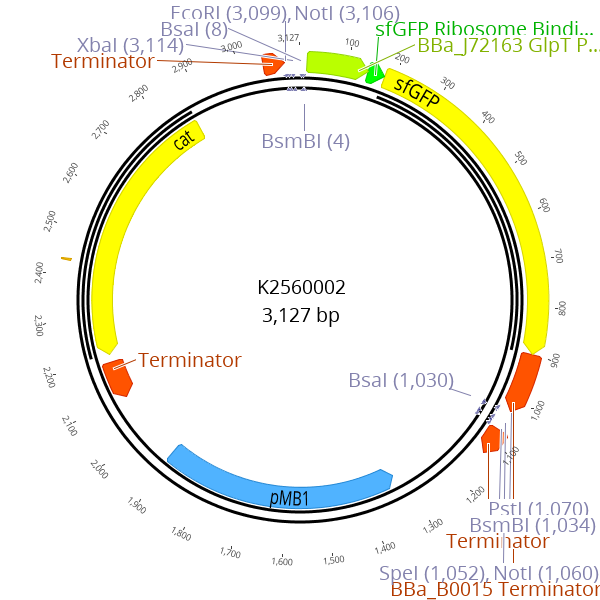

A sfGFP dropout cassette is flanked by BsmBI recognition sites. During the cloning of LVL0 parts with BsmBI, this dropout cassette is replaced by the desired part

We developed a solution for this problem by creating the novel resistance entry vectors BBa_K2560005 and BBa_K2560006. These plasmids contain a RFP and sfGFP dropout, respectively, and a chloramphenicol resistance cassette that is flanked by BsaI and BsmBI recognition sites. When a new LVL0 resistance part is cloned, the chloramphenicol resistance is replaced by the new antibiotic resistance marker resulting in a RFP or sfGFP expressing plasmid with the respective resistance marker. When using these LVL0 parts for LVL1 cloning, the re-ligated resistance parts yield colonies with a visually detectable phenotype. As a result, correct plasmids can be easily identified, even for inefficient LVL1 clonings with < 10 % efficiency.

Golden-gate based cloning relies upon the use of type IIs restriction endonucleases like BsaI, BsmBI or BpiI. In comparison to the commonly used type II restriction enzymes (e.g. EcoRI or PstI) they also recognize a specific DNA sequence but cleave outside of their recognition sequence (Pingoud and Jeltsch 2001). The golden-gate-cloning method is taking advantage of this property. A single enzyme can be used to create various single-stranded overhangs that match in a predefined order and finally lead to the correctly assembled plasmid (Engler et al. 2008).

When we started to design the Marburg Collection, we carefully investigated which fusion sites should be used. The fusion sites do not only set the order in which the single parts will be assembled but also affect the assembly efficiency and determine if a newly designed toolbox is compatible with already existing collections, so that parts can be shared easily. For us, the most important and decisive argument was that we wanted to be compatible with as many other toolboxes as possible. It is our strong belief that scientists all over the world should agree on one set of fusion sites to ensure complete interchangeability between different toolboxes. The toolboxes of MoClo (Weber et al. 2011), Loop Assembly (Pollak et al. 2018) and the PhytoBrick system already use a common set of fusion sites. We decided to adapt these fusion sites for all parts that build the transcription unit (Promoter, RBS, CDS, Terminator, Tags). Fusion sites for parts that are novel to our system (Connectors, Oris, Resistance cassettes) had to be newly designed by us because these parts did not exist in the other toolboxes.

We applied the following design principles to obtain optimal fusion sites. Firstly, the newly designed fusion sites must neither be identical to already existing fusion sites nor be palindromic to prevent assembly in a wrong order. Secondly, the fusion sites should not consist of bases that represent a portion of the recognition sequence of a restriction enzyme. If, for example, a fusion site with the sequence GGTC was used, and the sequence of the downstream part starts with TC, a BsaI recognition site would be reconstituted. So all fusion sites that would result in a partial recognition sequence of either BsaI, BsmBI or any of the enzymes that are used in the Biobrick cloning, are excluded. Lastly, the remaining candidates were sorted according to their GC content and the fusion sites with the highest GC content were chosen.

To make design of new parts as simple as possible, we created a collection of overhangs that can be copied from table xxxx and pasted to the sequence specific part of a primer to create new LVL0 parts. These primers contain the cut sites for integration into the part entry vector as well as the predefined fusion sites that are required for correctly assembling LVL1 plasmids. In some cases these overhangs contain additional bases that will be discussed in the following chapter.

Part Category

Fwd Overhang

Rev Overhang

1

5’ ConnectorAAGGTCTCGCTCGAACACGTCTCGNNNN

GGAGTGAGGGAGACCAA

2

PromoterAACGTCTCGCTCGGGAG

TACTTGAGGGAGACGAA

3

RBSAACGTCTCGCTCGTACTAGAG

TAATCAATGTGAGGGAGACGAA

4

CDSAACGTCTCGCTCGAATG

GCTTTGAGGGAGACGAA

5

TerminatorAACGTCTCGCTCGGCTTAA

CGCTTGAGGGAGACGAA

6

3’ ConnectorAAGGTCTCGCTCGCGCT

NNNNGGAGACGAGCTTGAGGGAGACCAA

7

OriAACGTCTCGCTCGAGCT

TGCTTGAGGGAGACGAA

8

ResistanceAACGTCTCGCTCGTGCTT

AACATGAGGGAGACGAA

4x

N-TagAACGTCTCGCTCGAATG

GGGATGTGAGGGAGACGAA

4y

N-tagged CDSAACGTCTCGCTCGGATG

GCTTTGAGGGAGACGAA

5a

C-TagAACGTCTCGCTCGGCTTTA

GGGTATGAGGGAGACGAA

5b

TerminatorAACGTCTCGCTCGGGTAA

CGCTTGAGGGAGACGAA

The fusion sites of most golden-gate-based cloning methods create a four base pair scar that is referred to as the fusion site. The fusion sites are the feature that makes toolboxes compatible with each other. Between some parts, additional bases are required for different reasons. These bases were chosen carefully to achieve best performance of the respective part. Please note that these additional bases are not a strict requirement to use or being compatible with our toolbox but we recommend them for the design of additional parts.

The first additional bases were incorporated between the Promoter and RBS part. The fusion site is TACT and AGAG was added additionally. The sequence between promoter and RBS that results by using our suggested overhangs form the same scar that is created if the the parts were assembled with 3A Assembly (Knight 2003). This means that the distance between promoter and RBS is not changed and therefore we do not expect negative effects in transcription or translation. Moreover, we hope that creating the same scar with a different method will make our experimental data more comparable to the data acquired with plasmids assembled with 3A Assembly in previous iGEM projects. The next bases were integrated between RBS and CDS parts. The fusion site, which was adapted from the PhytoBrick system, AATG and TAATC was added upstream of it. Previous work has shown that the sequence between a RBS and the start codon dramatically affects the expression of the desired protein (Lentini et al. 2013). A spacer length of six base pairs was shown to result in the strongest expression. When comparing different bases in a six bp spacer, the experimental data indicate significant differences. The 3A Assembly scar results in 50 % expression strength compared to the sequence TAATCT which was referred to as the reference (Lentini et al. 2013). We chose to use the spacer sequence which is expected to result in highest expression as we think that a system that is designed to enable strongest expression can be easily adapted for low expression by using weak RBS or promoters while going to the opposite direction might be more difficult. Unfortunately, we could not adapt the exact “reference sequence” because the first A in the fusion site AATG is already part of the spacer. Eventually, we used the first five bases of the strongest spacer (Lentini et al. 2013) upstream of the fusion site.

Between some parts, additional base pairs were integrated to ensure correct spacing and to maintain the triplet code. We expanded our toolbox by providing N- and C- terminal tags by creating novel fusions and splitting the CDS and terminator part, respectively.

One key feature of the Marburg Collection are the connectors that provide our toolbox with the required flexibility. Our design is inspired by the “Dueber Toolbox”, a golden-gate-based cloning method designed for applications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Lee et al. 2015). To our knowledge, the “Dueber Toolbox” is the first cloning system that performs assembly through all levels using restriction sites located on independent basic parts, termed connectors, instead of destination plasmids for level 1 and level 2 plasmids (Weber et al. 2011).

The connectors match in the following pattern: 5'Con(N) connects to 3'Con(N-1)

In already existing toolboxes, the combinatorics that come with choosing oris and resistances would be multiplied by the number of required positional vectors which provide the fusion sites for LVL2 assembly. A toolbox with five possible positions, four resistances and three oris would require 60 LVL1 destination plasmids. To enable inversion of transcription units, a built-in feature in our toolbox, the previous number would be multiplied by two, resulting in 120 required LVL1 destination plasmids.

Unsurprisingly, this theoretical toolbox would not be convenient to be built and used.

The Marburg Collection presents a novel approach that achieves maximum flexibility with a minimum of required components. We provide two sets of connectors. The first set, the “short connectors” solely provide the fusion sites for subsequent assembly. The fusion sites are identical to the ones that are used in building LVL1 plasmids to avoid having to design a complete new set of fusion sites. This also enables using LVL0 ori and resistance parts in LVL2 plasmids. Inversion of individual transcription units was also achieved by designing fusion sites that match in reverse order.

To achieve inversion, the respective transcription unit has to be built with connectors that match the neighboring transcription units. The function by following pattern: 3'Con(N)inv connects to 3'Con(N-1) and 5'Con(N)inv connects to 5'Con(N+1)

However, any other combination that follows the previously given rule will result in a functionally assembled LVL2 plasmid.

Design of insulators

In addition to the “short connectors”, we designed a set of “long connectors” that function as genetic insulators. They fulfill the same basic functions as the short connectors, providing fusion sites for subsequent cloning. Additionally, they consist of 300 bp “neutral DNA” flanked by two strong transcriptional terminators.The purpose of these long connectors is to reducing cross interaction between neighbouring transcription units, mainly transcriptional read through, a phenomenon that was described previously (Mairhofer et al. 2015). The design of “neutral DNA” started with generating 300 bp of random DNA which do not possess recognition sites of BsaI, BsmBI and any of the enzymes used in Biobrick Assembly, using a self-made Matlab script. These sequences were analyzed with the reverse mode of the R2oDNA designer (Casini et al. 2014). The R2oDNA designer can take a DNA sequence as input and quantifies the extent of secondary structures, repeats and forbidden sequence motifs, such as promoter or RBS motifs. Because the genome sequence of V. natriegens is not included in the tool, a BLAST search was performed manually with the sequences to check for homologies with the genome of V. natriegens. The top hit was considered as a fourth score to quantify the quality of a spacer sequence. At the end of this process, four scores were assigned to every sequence, each describing a different characteristic. We decided that spacer sequences with decent scores in each category are better suited as insulators than sequences with a superior score in one and inferior scores in other categories.

300 bp neutral DNA are flanked by two strong terminators. A BsmBI site for level 2 cloning is incorporated at the 5'end

The selected sequences were flanked by synthetic transcriptional terminators that were developed in the lab of Christopher A. Voigt (Chen et al. 2013). Most terminators were described to be unidirectional (Chen et al. 2013) and therefore the orientation of the flanking terminators had to be considered. Our priority was to prevent transcription into the respective transcription unit from the upstream sequence. Therefore each spacer sequence was equipped with a strong terminator at the 3’ and 5’ end of the 5’ connector in forward and reverse orientation, respectively.

We expect to achieve the best reduction of crosstalk between neighbouring transcription units by combining our insulators in combination with connectors that facilitate inversion of an individual transcription unit, thus providing a large step towards the reliable and predictable design of synthetic circuits.

In addition to this standard set of parts, our toolbox provides N- and C-terminal fluorescence and epitope tags to facilitate fluorescence microscopy and protein purification and degradation tags that can be used to finetune protein levels. Lastly, we submitted all project related parts that can be used to perform genome engineering via CRISPR/Cas9 or natural competence and all enzymes that were used in our metabolic engineering project.

The Marburg Collection is designed to be the most flexible golden-gate-based toolbox for prokaryotes. The high degree of flexibility of our toolbox is achieved by the de novo construction of plasmids instead of using entry vectors like most other toolboxes. A novel core feature are the connectors that provide the fusion sites for subsequent cloning steps and can be used to set the order and orientation of each individual transcription unit. A set of newly designed insulators, consisting of “neutral DNA”, and two transcriptional terminators, are designed to minimize crosstalk between neighbouring transcription units.

Our workflow

One of the central elements of synthetic biology is the Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle.

It illustrates the workflow of how systems like metabolic pathways, genetic circuits or anything else are constructed and evaluated.

The first step is to design the system basing on the existent knowledge about the system.

Then the system is built and its functionality is tested. The results of these tests describe the ‘Learning’ part of the cycle.

They are used to make an improved design.

Finally, a new round in the DBTL cycle can be made and the system gets improved in each round of the cycle.

For our approach we decided to establish a workflow for metabolic engineering, which bases on the DBTL cycle and combines the existing principles of metabolic engineering with the advantages of the fast-growing organism V. natriegens.

First of all, we use the Marburg Toolbox to construct a library of pathways with different combinations of promoters, ribosome binding sites, coding regions, enzyme ratios and plasmid copy numbers.

Next, we transform the plasmids for each pathway version together with the plasmid for the biosensor into our chassis. When the pathway is now performed, the cells produce a fluorescence or luminescence signal and its intensity correlates to the 3-hydroxypropionate ( 3HPA-) concentration.

By using FACS we can select for the most efficient pathway versions.

By using multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE), refeeding 3HPA into the central metabolism and repetition of FACS selection we have a cycle of directed evolution-guided pathway optimization.

The strains with the most promising pathway variants can then be isolated and their pathway composition elucidated.

Thus, we get information about designing principles for our pathway and can propose an improved design for a new round in the cycle of metabolic engineering.

To accelerate metabolic engineering we implemented a workflow based on the DBTL-cycle. Starting by building a library of pathway variants, they all can be introduced into V. natriegens as test chassis. By using biosensors FACS-directed selection of promising variants is possible. Cultivation and repeating of FACS leads to directed evolution and finally the most efficient strains can be analyzes to investigate the genetic composition. These finding can be feeded into the Learning-part of the DBTL-cycle thereby closing the workflow. Repeating the workflow continiously increases pathway efficiency and enables high-throuput metabolic engineering.

Our pathway

As mentioned in the description, there are many ways to produce 3HPA.

We decided for a pathway, basing on the conversion of acetyl-CoA via malonyl-CoA to 3HPA.

According to

(Valdehuesa et al. 2013)

who evaluated many pyruvate-derived production pathways from a thermodynamical point of view, this is one of the most efficient routes for 3HPA production.

We decided for this route for several reasons. First it bases on glucose degradation and V. natriegens has an unbeaten glucose-uptake rate, enabling a high glucose consumption rate. Second there is no vitamin B12 necessary, the only cofactors which are involved are NADPH and biotin, both of them naturally occurring in the organism.

Third there is theoretically just one further enzyme needed to complete the pathway.

All enzymes necessary for the production of malonyl-CoA are still present in V. natriegens and we just have to integrate the last enzyme, malonyl-CoA reductase.

Nevertheless, overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase increases productivity, so we took both enzymes into consideration.

(Kildegaard et al. 2016)

proposed, that there are many ways to further optimize the pathway and direct the flow to a high product titer. Hence, implementing many variations of this pathway into V. natriegens and testing them in a fast manner promises a high gain of knowledge about pathway optimization and general principles of metabolic engineering.

The pathway starts with pyruvate as product of glycolysis and other central metabolisms. Pyruvate is dehydrogenated by pyruvate dehydrogenase to acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA gets carboxylated by Acc to form malonyl-CoA. Malonyl-CoA is finally reduced to 3-hydroxypropionic acid by Mcr. Acc and Mcr are the two enzyme, we planned to express heterologously. Acc = Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Mcr = Malonyl-CoA reductase

Choice of enzymes

For the core pathway, we need to implement two enzymes, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc) and malonyl-CoA reductase (Mcr).

For Acc there are several candidates, which have still been tested for synthetic metabolisms

((Kildegaard et al. 2016);

(Liu et al. 2013);

(Vidra et al. 2017)).

Our plan was to first test enzymes from different organisms and then optimize expression profiles.

To benefit from the fast engineering workflow in V. natriegens, we decided to use enzymes from different organisms.

We planned to use the native Acc from V. natriegens, because it is still present in the cells and we prevent unnecessary burden by overexpressing a heterologous Acc.

The native Acc consists of four subunits together with an associated biotin ligase.

The genetic organization is the same like in E. coli, which is shown in figure 3. Nevertheless, further looks into literature revealed, that heterologous expression of pathway enzymes could be more promising because housekeeping Accs often are strictly regulated while foreign genes have different regulation motifs.

Hence, we also used the Acc from E. coli together with its associated biotin ligase (BirA). These enzymes have already been tested for 3HPA production

(Liu et al. 2013).

Additionaly, we decided to test the enzyme from Synechococcus elongatus. Since cyanobacteria require higher amounts of fatty acids to form thylakoid membranes, they might have more active enzymes.

The S. elongatus Acc consists of four subunits, just like those from E. coli and V. natriegens. For this enzyme it was also recommended to use it with a biotin ligase, because it needs a covalently bound biotin to be activ.

Unfortunately Accs consisting of four subunits form a very unstable complex and unbalanced expression levels of its subunits lead to gene repression

(Abdel-Hamid et al. 2006).

To circumvent this issue, we also chose the Acc from C. glutamicum.

In this organism, AccB and AccC are fused to one subunit, as well as AccA and AccD. Balancing of two subunits instead of four is much easier, therefore this enzyme is beneficial for us. Gande et al., 2007 still characterized this enzyme and confirmed its applicability for synthetic biology. Since C. glutamicum is a gram-positive bacterium, we decided to codon optimize the genes for a smoother translation and coexpressed the associated biotin ligase (Accession numbers NCgl0670, NCgl0678, NCgl0679).

In E. coli Acc is encoded by the genes accA, accB, accC, accD and the associated gene birA. In V. natriegens and S. elongatus there is the same genetic organization. Acc from C. glutamicum is encoded by only two genes, accBC and accD.

It was published that splitting of Mcr leads to increased activity, therefore beside the whole enzyme we also want to test the splitted version McrN + McrC and a combination of McrN and Mcr from S. tokodaii

Rational design of plasmids

Synthetic biology proceeded significantly in recent years and we have much knowledge about rational design of circuits and pathways.

Nevertheless, failures and unexpected outcomes slowdown scientific progress.

To tackle this issue, we decided to follow two approaches. On the one hand we planned to model our pathway and predict a – theoretically – optimal pathway, which we can then construct and test.

And on the other hand, we decided to build additionally to this particular pathway a whole library of many variations of this pathway with little differences.

In this way we create many producer strains in parallel and speed up the metabolic engineering workflow.

Our rational approach bases on a Michaelis-Menton-based metabolic analysis. For more details see our

metabolic model.

Since there are no stochiometric flux data about V. natriegens yet, we used the data from E. coli, which has a very comparable metabolome to V. natriegens (citation needed).

For the model we only considered acc from C. glutamicum and mcr from C. aurantiacus, because they were from our point of view the most promising ones.

The model predicted, that Acc is the rate limiting enzyme in the pathway and has to be expressed ten times stronger than Mcr.

We used the promoter characterization data, obtained from our part collection team (For more details see the section about

characterization of the promoters of our Marburg toolbox) and introduced them into the model.

The resulting prediction was, that we have to use the promoter J23106 for acc and J23109 for mcr. Therefore, we designed the pathway plasmid according to this model.

We built the plasmid based on the Marburg Toolbox with 4 transcriptional units. For the ori we chose ColEI, which has a broad host range and a high copy number in V. natriegens and E. coli

(Jain et al. 2013),

[Link zu qPCR von Carlos]).

We decided for that one, because V. natriegens shall be a chassis for testing pathway variants, which then maybe will be transferred into other strains, therefore a broad host range vector is reasonable.

For accBC and accD we chose the promoter J23106 and for mcr the promoter J23109 according to the model. For birA we also chose J23109 as promoter, because BirA is only relevant for activation of Acc and not for direct reaction catalysis. For ribosome binding sites and terminators, we used the same for each coding region, because otherwise we would have fluctuations which weren’t considered in the model.

An illustration of the plasmid is shown in figure 5.

![The scheme shows the composition of the level 2 plasmid, containing four transcriptional units for accBC, accD, birA and mcr. We chose the promoters according to the metabolic model [LINK] to achieve optimized expression strengths. accBC consists of 5'-Con1, J23106, B0030, accBC, B0015 and 3'-Con1, accD consists of 5'-Con2, J23106, B0030, accD, B0015 and 3'-Con2, birA consists of 5'-Con3, J23109, B0030, birA, B0015 and 3'-Con3, mcr consists of 5'-Con4, J23109, B0030, mcr, B0015 and 3'-Con5.](https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/33/T--Marburg--Rational_Plasmid.png)

The scheme shows the composition of the level 2 plasmid, containing four transcriptional units for accBC, accD, birA and mcr. We chose the promoters according to the metabolic model [LINK] to achieve optimized expression strengths.

Pathway library

For the second approach of pathway design, where we build a whole library, we also used the Marburg Toolbox [Marburg Toolbox soll ein Link zur Marburg Toolbox sein] to combine different promoters, ribosome binding sites and coding regions. In theory, the toolbox enables the plasmid assembly of 21780 different part combinations per transcriptional unit (22 promoters x 5 rbs x 6 terminators x 3 oris x 11 resistance cassettes; connectors weren’t considered). For a plasmid containing accBC, accD, birA and mcr that would make 6 x 1012 possible constructs, but assembly of so many versions is irrational. The better way is to select a few parts which are combined and then for the most promising versions one can think of more combinations. Therefore, we focused on eight promoters and three ribosome binding sites with different strengths. Our idea was to build pathway plasmids containing the whole pathway, as well as plasmids containing only the acetyl-CoA carboxylase genes or only the mcr gene, which can then be cotransformed (Table 1). To enable cotransformation, we used the oris ColEI and p15a, which are compatible to each other.

| Plasmid Category | Inserts | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | mcr | These plasmids contain the whole mcr gene from C. aurantiacus and can be cotransformed with each ColEI plasmid, because they have a p15a ori. |

| II | mcrN mcrC |

These plasmids contain the dissected mcr fragments from C. aurantiacus and can be cotransformed with each ColEI plasmid, because they have a p15a ori. |

| III | mcrN mcrSt |

These plasmids contain the N-terminal mcr fragments from C. aurantiacus and the mcr from S. tokodaii. They can be cotransformed with each ColEI plasmid, because they have a p15a ori. |

| IV | accBC accD birA |

These plasmids contain all required genes for the acetyl-CoA carboxylase from C. glutamicum and can be cotransformed with each p15a plasmid, because they have a ColEI ori. |

| V | accBC accD birA mcr |

These plasmids contain all genes for the complete pathway. They combine the Acc from C. glutamicum with Mcr from C. aurantiacus. |

| VI | accBC accD birA mcrN mcrC |

These plasmids contain all genes for the complete pathway. They combine the Acc from C. glutamicum with the dissected Mcr from C. aurantiacus. |

| VII | accBC accD birA mcrN mcrSt |

These plasmids contain all genes for the complete pathway. They combine the Acc from C. glutamicum with the N-terminal Mcr-domain from C. aurantiacus and Mcr from S. tokodaii. |

The idea behind the plasmids with the whole pathway is, that the cells only have to maintain one particular plasmid. The strategy for the single-enzyme plasmids is that by cotransformation different combinations can be made to increase the number of possible pathway variants. The different plasmid types can be seen in table 1, all in all we designed the construction of 1446 plasmids for our pathway library. For plasmids of category I (see table 1), we combined eight promoters with three ribosome binding sites, a kanamycin resistance gene and a p15a ori, giving us 24 constructs. For plasmids of category II and III we used the same promoters and ribosome binding sites for both transcriptional units, leading to 576 plasmids respectively. For plasmids of category IV we restricted our selection to three promoters and three ribosome binding sites. Since a misbalance of accBC- and accD expression levels leads to occlusion bodies and decreased activity we decided to always use the same promoters and rbs for both genes. In this category we get 81 plasmid variants. For categories V, VI and VII, containing the whole pathway, the combinatorial possibilities were very high, so we decided to further restrict the selection by always coupling strong promoters to strong rbs, medium promoter to medium rbs and weak promoter to weak rbs. Therefore, we got a total of 27 plasmids for category V and 81 plasmids for category VI and VII, respectively. We also considered to integrate one or several genes, therefore we planned to search for integration sites and to characterize them. [Link zu Bauersachs Teil]

Our biosensors

The design of our biosensors was largely guided by the goal of having as little impact on the host metabolism, while simultaneously being simple and easy to implement. We chose to design all parts to be compatible with the Marburg toolbox, RFC10, RFC25, andRFC1000,

to make it as easy as possible for us and future users to implement it and adapt it to new requirements.

This part enables creation of new LVL0 parts by replacing the parts sequence with the desired insert. The sfGFP expression cassette is flanked by BsmBI recognition sites

Annotation of the location for the regulatory sequences upstream of the HdpR coding sequence was insufficient for us to precisely remove the activator binding site or the constitutive promoter driving HdpR expression. So, we included an about 200bp long region upstream of the HdpR, which should be enough to include all regulatory motifs. Also included is the HdpR coding sequence with its own ribosomal binding site (RBS). and promoter. This results in a part that includes the whole sensing function, but does not quite fit our scheme of clearly defined functional units. Since expression of any part cloned behind the regulatory region is directly controlled by it, and the part serves as both, a promoter and RBS. It is basically an inducible promoter fused to an RBS. Thus, we decided to give the part the overhangs of an RBS. on the downstream and a promoter on the upstream end.

In order to obtain the desired region from the P. putida KT2440 genome, we planned to amplify it via PCR and then isolate the fragment by gel purification of the corresponding band. Into the primer-design we factored in the overhangs we needed to make it Marburg toolbox compatible. So, we gave them non-binding overhangs which automatically added the necessary BsmBI cut sites.

This sensor consists of two unique level 0 parts that combined with the lux operon as reporter constitute the biosensor

For the malonyl-CoA sensor, our proceeding was very similar. Just that we knew the exact location of all functional parts, except of the location of the promoter, form the 2015 paper by Liu et al and from annotations in the published genome (Liu et al. 2015). Therefore, we could implement it fully into the Marburg toolbox, by simply treating the FapR coding sequence as coding sequence. Not that straightforwardly was the design of the fapO regulator binding site. Since we did not know the promoter strength, and the mechanism of regulation was independent of the promoter sequence, we decided to implement a promoter from the Andersen library, J23100. By placing it right in front of the fapO site, we created a construct that, in theory, should give us a FapR controlled promoter. For the amplification of the individual parts from the B. subtilis 168 genome, again, we used primers sporting non-binding regions, adding the necessary overhangs for our toolbox.

For future projects, other sensors could also be employed. In a publication from 2016, Rogers et al. propose an alternative sensor for 3HPA with a lower perception threshold (Rogerset al.2016). We choose not to implement it in our design because of its more complicated mechanism that requires the implementation of more genes. Intriguingly, it works by first converting 3HPA to acrylate via a pathway of three heterologous enzymes. The acrylate is then sensed by a transcription factor, similarly to how our sensors described above work. They also report its successful implementation and application in increasing the 3HPA titer up to 23-fold. It is conceivable that with a little more effort our system could yield comparable results. Off cause, s we have the additional benefit of having a much shorter iteration interval.

The malonyl-CoA Sensor FapR is a dimeric protein which binds to the fapO operator, thereby inhibiting expression of the reporter gene. When malonyl-CoA is bound, the regulator dissociates from the DNA and gene expression can occur. The Sensor for 3-hydroxypropionate works reversely. In the absence of 3HPA the 3HPA sensor HpdR binds to its operator, allowing the polymerase to read the HpdR promoter.

Further product sceening

The usage of biosensors for product screening is a fast and cheap method enabling high throughput analysis of pathway libraries.

However, to further characterize the pathway variants and implemented enzymes we planned to measure enzyme activities.

In that way we can quantitatively benchmark each enzyme and establish in vitro assays as a prototyping engineering approach.

For the malonyl-CoA reductase, it is easy to measure reaction velocity, because the enzyme converts NADPH into NAD+ and both compounds have different absorbances at 345nm

(De Ruyck et al. 2007).

Based on that we designed an enzyme assay, where we use cell extract from Mcr producing cells or directly purified Mcr and mixed it with a defined amount of NADPH and MgCl2.

By measuring the absorbance, one can determine if NADPH concentration changes.

By adding malonyl-CoA to the reaction mix we then start the reaction and are able to observe a decrease in absorbance because the reaction consumes NADPH.

Here the starting concentrations of malonyl-CoA and NADPH have to be high enough to ensure, that nearly each Mcr molecule in the mixture is saturated and the reaction goes proportional to enzyme concentration.

By determining the slope of the linear decrease of absorbance it is possible to calculate the specific activity.

The specific activity is a value which characterizes the ability of enzymes, to convert a substrate into a product.

It is defined as the moles of product formed by an enzyme in a given amount of time under given conditions per milligram of total proteins, the unit is µmol min-1mg-1.

To calculate the specific activity, one needs the slope of the measured absorbance. This value defines the change of absorbance per time.

By using the Lambert-Beer law it is possible to calculate the amount of NADPH converted into NADP+ per time

(Lambert and Anding, 1760).

ε is 3400 M-1cm-1 and d is 1cm. By dividing with time and enzyme volume, we get the final formula to calculate the NADPH conversion per time.

Since one conversion of malonyl-CoA corresponds to two conversions of NADPH, we can calculate, how much malonyl-CoA is consumed per time. This value is defined as enzyme activity with the unit µmol/min and depends on the enzyme amount. By taking the protein amount into consideration, the specific activity can be calculated:

For Acc the enzyme assay must be redesigned because carboxylation of acetyl-CoA doesn’t consume NADPH or other photometrically measurable compounds.

Therefore, we decided to do a coupled enzyme assay, where we not only add Acc (or Acc containing cell extract) into the reaction mixture but also purified Mcr as indicator enzyme which metabolizes malonyl-CoA as product of Acc and thereby converts NADPH to NAD+.

It is crucial to add large amounts of Mcr into the mixture to ensure, that Acc is the rate-determining enzyme and not Mcr. For the Acc activity assay we planned to mix purified Acc or cell extract with ATP, MgCl2, NaHCO3, purified Mcr and NADPH. Our strategy was to start the reaction by adding Acetyl-CoA as precursor for all reaction steps and then measure absorbance loss just like in the Mcr assay.

The calculations for the specific activity are also the same.

Beside evaluating enzyme performances, we also wanted to specifically detect and quantify 3HPA in our cells.

We planned to do that via HPLC and mass spectrometry. Establishing a HPLC/Mass spectrometry protocol is also essential for calibrating our biosensors.

The identification of malonyl-CoA as intermediate of our pathway is not so challenging because the CoA appendix lends it a larger mass of 853.12g/mol, which is specific for malonyl-CoA.

For 3HPA the specific identification is more difficult because V. natriegens is able to fermentatively produce lactate, a structural isomer of 3HPA.

To distinguish between 3HPA and lactate we chose to use a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

In such a device two quadrupole mass analyzers are toggled in a row and separated by a third quadrupole, responsible for the collision-induced dissociation of ions.

Our strategy was to cultivate cells, performing the 3HPA pathway or at least one of its reaction steps and then lysate the cells and measure lactate- as well as 3HPA-concentrations in the cell extract and also in the medium, because there are no hints if 3HPA stays in the cell or is released into the medium.

Directed evolution

Metabolic Engineering offers many possibilities to create suitable pathways but it consists of more than just building them. Pathway optimization is also crucial for efficient productivity.

In our workflow for metabolic engineering we want to implement directed evolution to drive metabolic fluxes towards 3HPA production.

We elaborated two strategies to do that. Our first strategy was to implement genes for the conversion of 3HPA into succinate.

In that way, we lead our product back into the central metabolism.

By deleting all other genes responsible for succinate production, the cells are forced to use the 3HPA bypass to get succinate, which is needed in the TCA cycle.

The big advantage of using V. natriegens for that purpose is that its short doubling time increases the number of cell divisions per time and thereby increases the number of mutations in a given time frame. Our second strategy is to use MAGE [Link zu project→description→metabolic engineering→Directed evolution→MAGE erklärung] together with our biosensors and fluorescence-activated cell sorting ( FACS ), to cause various genome modifications and rapidly select for cells with increased 3HPA productivity (Figure 9).

We looked into literature and found 16 possible genome modifications for 3HPA production made by other groups.

Table 2 shows a list of all modifications.

Our plan was to order oligos for each of these modifications, leading to upregulation, downregulation, deletion or site-directed mutagenesis of the respective gene.

The aimed modification for each gene is shown in the table. For the next step we decided to use natural transformation for integration of these oligos into the strain.

Because each cell will take up different numbers and different combinations of oligos, we will get a population of genomic variations [Link zu Project → Design → Strainies → Mugent].

The genetically diverse population can then be put into FACS and we can select for cells with the strongest signal and thereby the best productivity.

Finally, the whole cycle of MAGE and FACS can be repeated, leading to continuously improved pathways. We believe that the combination of MAGE- FACS with the fast growth of V. natriegens will speed up the process of metabolic engineering and pathway optimization significantly!

To use the fast growth of V. natriegens we designed a workflow for directed evolution. It combines MAGE with FACS and starts with the introduction of oligos for genome modifications into our strain. The usage of randomized oligos with variable bases increases the genetic diversity. By using FACS together with our biosensors we are able to rapidly select the most promising strains and can analyse their genetic composition. This finding can be re-feeded into the DBTL-cycle to start a new round in the workflow leading to a continously improved pathway.

Outlook

In our project we try to accelerate the process of metabolic engineering in all of its facets and thereby find a suitable pathway variant to achieve high 3HPA productivity.

Nevertheless, there will still be many possibilities to further improve the production of 3HPA in V. natriegens. Table 2 shows a list of 16 genome modifications, that were made in other organisms with the same or a similar pathway to direct the flow towards 3HPA.

Some of these modifications target for instance NADPH homeostasis.

During glycolysis cells produce NADH while the production of 3HPA depends on NADPH.

Therefore, a misbalance between NADH and NADPH could arise, but overexpression of pntAB (nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase) or gapA (NADP+-dependent glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) has been shown to stabilize cofactor balance (See table for references). Another possibility to enrich the NADPH pool is to downregulate glycolysis while upregulating pentose phosphate pathway, which produces NADPH instead of NADH.

This can be achieved by deletion of NAD+-dependent gapA or deletion of pfkA (phosphofructokinase). Another critical point in the 3HPA route are side reactions.

Pyruvate can be reduced to lactate or decarboxylated to acetate, what could be suppressed by deletion of ldhA (lactate dehydrogenase) or pox (pyruvate decarboxylase).

The flow from pyruvate to acetyl-CoA can be increased by overexpression of pdh (pyruvate dehydrogenase).

For acetyl-CoA there are also side reactions, for instance hydrolysis to acetate. This reaction can be suppressed by deletion of pta (phosphotransacetylase) and ackA (acetate kinase) or by overexpression of ald6 (aldehyde dehydrogenase) and acs (acetyl-CoA synthase) for the reverse reaction to acetyl-CoA.

Malonyl-CoA can also go into side reactions for fatty acid biosynthesis instead of the reduction to 3HPA.

However, downregulation of fabAB (fatty acid biosynthesis) or inducible inactivation of fabAB has been showed to increase 3HPA titer.

Additionally it has also been shown that site-directed mutagenesis of acc and mcr genes increases product titer (Kildegaard et al. 2016);

(Liu et. al. 2016).

| Gene | Organism | Function | Modification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gapA | S. cerevisiae | GAPDH (NADP-dependent) | Overexpression | (Chen et. al. 2014) |

| mis1 | S. cerevisia | malate synthase | Deletion | (Chen et. al. 2014) |

| pox | E. coli | pyruvate decarboxylase | Deletion | (Dittrich et. al. 2008) |

| acc1 | S. cerevisiae | acetyl-Coa carboxylase | Site-directed mutagenesis | (Kildegaard et al. 2016) |

| ald6 | S. cerevisiae | aldehyde dehydrogenase | Overexpression | (Kildegaard et al. 2016) |

| pdh | S. cerevisiae | pyruvate dehydrogenase | Overexpression | (Kildegaard et al. 2016) |

| acs | E. coli | acetyl-CoA synthase | Overexpression | (Lin et. al. 2006) |

| bauA | From P. putida into E. coli | beta-ala-pyruvate aminotransferase | Complementation | (Liu et. al. 2016) |

| panD | E. coli | aspartate-1-decarboxylase | Deletion | (Liu et. al. 2016) |

| ackA | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | acetate kinase | Deletion | (Rathnasingh et al. 2012) |

| ldhA | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | lactate dehydrogenase | Deletion | (Rathnasingh et al. 2012) |

| pta | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | phosphotransacetylase | Deletion | (Rathnasingh et al. 2012) |

| sucAB | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | 2-oxo-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | Deletion | (Rathnasingh et al. 2012) |

| gapA | C. glutamicum | GADPH | Deletion | (Siedler et. al. 2013) |

| pfkA | C. glutamicum | phosphofructokinase | Deletion | (Siedler et. al. 2013) |

| fabAB | E. coli | fatty acid biosynthesis | Downregulation | (Yang et. al. 2015) |

| pntAB | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | nicotinamide nucleotide tranhydrogenase | Overexpression | (Rathnasingh et al. 2012) |

| mcrC | E. coli (from C. aurantiacus) | malonyl-CoA reductase | Site directed mutagenesis | (Liu et. al. 2016) |

We chose the production of 3HPA as application to show the functionality of the Marburg toolbox and as proof-of-principle for our metabolic engineering workflow. However, our goal is not to produce high amounts of 3HPA, but rather to show that V. natriegens can be used as test chassis for rapid testing of many pathway variations to find the best one. The next step would therefore be to evaluate, if the pathway with its genetic composition can be transmitted to other organisms to see if the route still works. Besides that, there are many other compounds of medical and economical relevance, which still can’t be produced biotechnologically. The production of the anticancer drug taxol involves for instance 19 enzymes and is therefore a very challenging pathway with lot of bottlenecks and tunable reactions (Croteau et al., 2006). We think it would be beneficial to use V. natriegens as chassis for testing this challenging pathway or parts of it. Its short doubling time and genetic accessibility will accelerate the process of enzyme engineering and finetune expression levels or gene combinations. Another crucial aspect, that has to be tackled is the universality of our workflow. We involved biosensors for product screening but for many metabolites there are still no known sensor proteins. There are three possibilities to circumvent this issue. The first is to find new biosensors, what is complicated, because many compounds, especially drugs for medical purposes don’t occur in the nature, therefore it is unlikely that there are still proteins binding specifically to these compounds. The second possibility would be to engineer proteins to become drug-specific sensors. The third possibility is to upscale LC-MS techniques to enable larger sets of measurements and faster screening. LC-MS has an unbeaten accuracy but its bottleneck is the velocity. The average time needed for one sample lies between 1 and 10 minutes, making measurements of large sets of samples impossible. Furthermore LC-MS requires high amounts of buffer. However, as mentioned in the Labautomation-section [soll ein Link sein], the company Labcyte developed a system to use acoustic waves for pipetting nanoliter droplets into microtiter plates in a very fast manner. Now they invented an acoustic mass spectrometer, which combines acoustic nanodroplet formation with mass spectrometry. The device is able to measure 3 samples per second without the need of a mobile phase. Such a device could be used instead of biosensor-based flow cytometry to broader the applicability of our metabolic engineering workflow.

References

Abdel-Hamid, A.M., Cronan, J.E., 2007. Coordinate expression of the acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase genes, accB and accC, is necessary for normal regulation of biotin synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189, 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.01373-06Chen, Y., Bao, J., Kim, I.-K., Siewers, V., Nielsen, J., 2014. Coupled incremental precursor and co-factor supply improves 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 22, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2014.01.005

Croteau, R., Ketchum, R.E.B., Long, R.M., Kaspera, R., Wildung, M.R., 2006. Taxol biosynthesis and molecular genetics. Phytochem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-005-3748-2

De Ruyck, J., Famerée, M., Wouters, J., Perpète, E.A., Preat, J., Jacquemin, D., 2007. Towards the understanding of the absorption spectra of NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ as a common indicator of dehydrogenase enzymatic activity. Chem. Phys. Lett. 450, 119–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2007.10.092

Dittrich, C.R., Vadali, R. V., Bennett, G.N., San, K.-Y., 2008. Redistribution of Metabolic Fluxes in the Central Aerobic Metabolic Pathway of E. coli Mutant Strains with Deletion of the ackA-pta and poxB Pathways for the Synthesis of Isoamyl Acetate. Biotechnol. Prog. 21, 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp049730r

Gande, R., Dover, L.G., Krumbach, K., Besra, G.S., Sahm, H., Oikawa, T., Eggeling, L., 2007. The two carboxylases of Corynebacterium glutamicum essential for fatty acid and mycolic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5257–5264. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00254-07

Hügler, M., Menendez, C., Schägger, H., Fuchs, G., 2002. Malonyl-coenzyme A reductase from Chloroflexus aurantiacus, a key enzyme of the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic CO(2) fixation. J. Bacteriol. 184, 2404–10. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.184.9.2404-2410.2002

Jain, A., Srivastava, P., 2013. Broad host range plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 348, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6968.12241

Kildegaard, K.R., Jensen, N.B., Schneider, K., Czarnotta, E., Özdemir, E., Klein, T., Maury, J., Ebert, B.E., Christensen, H.B., Chen, Y., Kim, I.K., Herrgård, M.J., Blank, L.M., Forster, J., Nielsen, J., Borodina, I., 2016. Engineering and systems-level analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid via malonyl-CoA reductase-dependent pathway. Microb. Cell Fact. 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-016-0451-5

Lambert, J.H., Anding, E., 1760. Photometrie. Photometria, sive De mensura et gradibus luminis, colorum et umbrae (1760) : Lambert, Johann Heinrich, Internet Archive, Photometria, sive De mensura et gradibus luminis, colorum et umbrae. Eberhardt Klett, Augsburg.

Lin, H., Castro, N.M., Bennett, G.N., San, K.-Y., 2006. Acetyl-CoA synthetase overexpression in Escherichia coli demonstrates more efficient acetate assimilation and lower acetate accumulation: a potential tool in metabolic engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 71, 870–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-005-0230-4

Liu, C., Ding, Y., Zhang, R., Liu, H., Xian, M., Zhao, G., 2016. Functional balance between enzymes in malonyl-CoA pathway for 3-hydroxypropionate biosynthesis. Metab. Eng. 34, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.001

Liu, C., Wang, Q., Xian, M., Ding, Y., Zhao, G., 2013. Dissection of Malonyl-Coenzyme A Reductase of Chloroflexus aurantiacus Results in Enzyme Activity Improvement. PLoS One 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075554

Liu, D., Xiao, Y., Evans, B.S., Zhang, F., 2015. Negative Feedback Regulation of Fatty Acid Production Based on a Malonyl-CoA Sensor-Actuator. ACS Synthetic Biology 4, 132-40 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24377365

Rathnasingh, C., Raj, S.M., Lee, Y., Catherine, C., Ashok, S., Park, S., 2012. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid via malonyl-CoA pathway using recombinant Escherichia coli strains. J. Biotechnol. 157, 633–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.06.008

Rogers, J.K. & Church, G.M., 2016. Genetically encoded sensors enable real-time observation of metabolite production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2388-93. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600375113

Siedler, S., Lindner, S.N., Bringer, S., Wendisch, V.F., Bott, M., 2013. Reductive whole-cell biotransformation with Corynebacterium glutamicum: improvement of NADPH generation from glucose by a cyclized pentose phosphate pathway using pfkA and gapA deletion mutants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4314-7

Valdehuesa, K.N.G., Liu, H., Nisola, G.M., Chung, W.J., Lee, S.H., Park, S.J., 2013. Recent advances in the metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid as C3 platform chemical. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 3309–3321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-013-4802-4

Vidra, A., Németh, Á., 2017. Bio-based 3-hydroxypropionic Acid : A Review. period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 1–11. Yang, Y., Lin, Y., Li, L., Linhardt, R.J., Yan, Y., 2015. Regulating malonyl-CoA metabolism via synthetic antisense RNAs for enhanced biosynthesis of natural products. Metab. Eng. 29, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.018