RESULTS

The whole Cerberus project is based on the construction and validation of a proteic platform to link very different molecules together. This platform is composed of three heads. The first head is a CBM3a domain which specifically binds cellulose. The second head is a streptavidin domain with a strong affinity to biotinylated compounds. The third head is based on the presence of an unnatural amino acid to covalently link any molecule with an alkyne moiety.

To validate the Cerberus platform, we worked head by head, starting from the CBM3a validation, then the streptavidin domain assessment and finally the demonstration of the unnatural amino acid capacity to covalently bound alkynilated molecules. Thus, our first construction has only one head and was named Sirius, after the brightest star of the northern hemisphere, alpha canis majoris. The second construction presents both the CBM3a and streptavidin heads and was nicknamed Orthos, a two-headed mythological dog. The final construction is Cerberus with its three heads.

Sirius: CBM3a

Background

Sirius is a fusion protein between CBM3a and mRFP1. This design, which consists of fusing CBM3a to a fluorescent moiety, allowed us to investigate the binding capability of the CBM3a domain to cellulose through the four aromatic amino acids of its binding domain. mRFP1 was chosen since it is both a coloured and fluorescent protein.

Key Achievements

-

Cloning of the part encoding Sirius

-

Overexpression and purification of Sirius

-

Fixation of Sirius to cellulose

Materials and Methods

The fused CBM3a and mRFP1 sequences were cloned into the pET28 expression vector in fusion with a histidine tag (Figure 1).

The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli strain and expression of the recombinant protein was induced using IPTG. The His-tagged protein was then purified on IMAC resin charged with cobalt and used in cellulose pull down assays. For the experimental details, see Experiments page.

Results and Discussion

Production and purification of Sirius

Interestingly, E. coli turned a deep pink shade after induction, indicating a strong production of Sirius (Figure 2).

As shown in Figure 3, we successfully purified the Sirius protein. Indeed, induction with IPTG produced a large amount of a protein at the expected size for Sirius (52 kDa, lane CFE). This protein was then found to be predominant in elution samples (E1/40 and E1/100). We estimated the degree of purity of full-length Sirius at about 72%. In addition to the full-length protein, we observed several extra bands that likely correspond to proteolysis products.

Validation

Once produced in

When mRFP1 was added alone to cellulose, its associated colour mostly remained in the supernatant (Figure 4). When Sirius was associated with cellulose, the pinkish colour was clearly associated to the cellulose pellet. Quantification of the cellulose-associated fluorescence backed up these observations (Figure 5): control experiments showed that only background levels of fluorescence are retained in the cellulose pellet incubated with mRFP1 alone. These experiments have been performed in triplicate and statistical analyses indicate that the high level of fluorescence obtained with Sirius is definitively significant. These results clearly show that the CBM3a domain of Sirius interacts with cellulose, and thus mediates binding of mRFP1 protein to cellulose.

Orthos: Streptavidin and biotinylated compounds

Background

The next step was to assess the binding capacity of the streptavidin linker. Orthos, named after the guardian of Geryon's cattle, is a fusion protein between CBM3a and a monomeric streptavidin head. The strong affinity of streptavidin for biotin (dissociation constant of 10-13 M) will allow biotinylated organic molecules to be tightly bound to Orthos. We used two types of biotinylated compounds to monitor the ability of our platform to functionalise cellulose: fluorophores (mTagBFP and fluorescein) and antimicrobial peptide (scygonadin).

Key Achievements

-

Cloning of the part encoding Orthos

-

Production of Orthos carrying monomeric streptavidin

-

Production of biotinylated fluorophores in vitro and in vivo

-

Functionalisation of cellulose with biotinylated compounds

Materials and Methods

The fusion between monomeric streptavidin and CBM3a was cloned into the pET28 expression vector. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli strain BL21 DE3 and expression of the recombinant protein was induced using IPTG. For Orthos, the histidine tag present on pET28 is not be fused to the CBM3a domain since an amber Stop codon is present between them (Figure 1). The protein was therefore not purified on the IMAC column but purified on Regenerated Amorphous Cellulose (RAC) and used in cellulose pull down assays. For the experimental details, see our experiments page.

Results and Discussion

Purification of Orthos

Figure 2 presents the results of the purification of Orthos on RAC. The supernatant (S) contained all proteins produced in E. coli, and washes W1 and W2 allowed the elimination of most non-specific interactions with cellulose. The elution step, using ethylene glycol, released the Orthos protein from RAC. The band at about 40 kDa corresponds to Orthos (expected size: 39 kDa) and the band at 15 kDa likely corresponds to a proteolysis fragment of Orthos containing only the CBM3a module.

We estimated that the purification levels of the monomeric Orthos was about 45%, which is sufficient for our validation assays.

Validation of monomeric Orthos

Validation using in vivo biotinylation

In a first set of experiments, we assessed the ability of Orthos to functionalise cellulose with a compound biotinylated in vivo. For that purpose, we took advantage of a novel system for in vivo protein biotinylation using the biotin ligase BirA. We thus co-expressed BirA and a version of the Blue Fluorescent Protein (BFP) fused to an Avitag in E. coli. The Avitag sequence is recognized by BirA for biotin ligation. We added biotin to the culture medium during IPTG induction, in order to produce and purify biotinylated BFP.

We then incubated 3.2 μM of Orthos with 32 μM of in vivo biotinylated BFP (Figure 3). For the control experiment BFP (without Orthos), the same quantity of BFP was added to permit a relevant comparison. These samples were then incubated with cellulose. After three washes with Tris-HCl buffer, fluorescence was measured in the cellulose pellets. As shown in Figure 3, fluorescence is twice as intense in Orthos sample than in the control sample containing BFP alone. These experiments have been performed in quadruplicate and a Mann Whitney statistical test indicated that the increased fluorescence signal obtained with Orthos is significant.

These results demonstrate that Orthos binds efficiently to an in vivo biotinylated compound. In addition, they show that Orthos binds to cellulose and thus provide proof of principle that Orthos design allows functionalisation of cellulose with a fluorophore through its streptavidin linker.

Validation using in vitro chemical biotinylation

In a second set of experiments, we tested the ability of Orthos to functionalise cellulose with in vitro biotinylated compounds. Since we had both an azide-functionalised fluorescein (FAM-azide) and biotin-DBCO (an alkyne moiety), we imagined to combine both to produce biotinylated FITC. In addition, it was a nice way to challenge this click chemistry technology. We used the newly emerging technique Cu(I)-free strain-promoted alkyne-azide click chemistry (SPAAC) allowing the coupling in vitro of a molecule containing a dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) moiety to another molecule bearing an azide function. We used this technique to ligate in vitro biotin-DBCO to an azide-functionalised fluorescein (FITC), thus leading to the expected biotinylated FITC.

Then, 58.0 μM of biotinylated FITC was incubated with 5.8 µM of Orthos protein. The same amount of FITC alone (58.0 μM) was used for the control experiment. These samples were incubated with cellulose and after five washes with Tris-HCl buffer, fluorescence levels were measured in the cellulose pellet fractions (Figure 4). In the presence of Orthos, fluorescence in the cellulose pellet was about twice as high as in control experiments corresponding to the cellulose pellet incubated with FITC alone (without Orthos) or with the reaction buffer only. These experiments were performed in quadruplicate and a Mann Whitney statistical test indicated that the increased fluorescence signal obtained with Orthos is very significant. This result clearly shows that purified Orthos retains the ability to mediate the interaction between cellulose and a compound biotinylated in vitro. In addition, this result provides another strong evidence that Orthos allows cellulose to be functionalised using a fluorescent molecule through its streptavidin linker. It also shows that we succeeded in creating biotinylated FITC by click chemistry.

Validation using scygonadin

In order to confirm that the streptavidin moiety of Orthos is able to interact with different kind of biotinylated compounds, we also tried to bind it to an antimicrobial peptide, the scygonadin. To biotinylate this compound, we used the in vivo protein biotinylation system as the one used for BFP molecule. We co-expressed BirA with a version of scygonadin fused to the Avitag in Pichia pastoris.

We then incubated Orthos with in vivo biotinylated scygonadin, and few hours later, we added cellulose (under form of a cellulose spot). After two washes with Tris-HCl buffer, cellulose spots with Orthos-scygonadin were deposed on Petri dish pre-inoculated with a E. coli layer. We observed small halos of inhibition for some samples after incubation overnight (Figure 5).

We noticed that the inhibition halo was more important for the Orthos-scygonadin sample than the scygonadin alone control. Unfortunately, we repeated this test, but we did not obtain the same result. Therefore, we need to improve our experiment to prove the coupling between Orthos and biotinylated scygonadin. These results are nevertheless encouraging in the perspective of functionalising cellulose using Orthos bound to antibiotic protein.

Perspectives

Our experiments using different kinds of biotinylated compounds provide convincing proofs of concept that Orthos can be conjugated, via its streptavidin head, to biotinylated organic molecules. The resulting molecules interact with cellulose and are therefore potent cellulose functionalising compounds.

We can now envision exploiting the streptavidin linker of Orthos to ligate various compounds that can be biotinylated chemically (in vitro) or in vivo, via BirA co-expression.

In addition, we incorporated a TEV protease cleavage between the N-terminus linker and the streptavidin. This will allow to produce Orthos-bound biotinylated compounds that can be released by TEV cleavage if required, as in the case of odorant molecules for examples for a commercial use.

Cerberus: AzF

Background

Cerberus, named after the guardian of the gates of the Underworld, is our three-headed protein made of the cellulose-binding molecular platform (CBM3a) fused at the N-terminus to the biotinylated molecule-binding head (monomeric streptavidin) and at the C-terminus to the unnatural amino acid azido-L-phenylalanine (AzF). The incorporation of AzF is achieved through the recognition of the amber stop codon at the C-terminus of CBM3a by an orthogonal AzF-charged tRNA.

Coupling of molecules to the AzF head can be performed by click chemistry, either through SPAAC or through Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne click chemistry (CuAAC). To prove the versatility of the system, different compounds such as fluorescent proteins or paramagnetic beads have been clicked onto Cerberus and thus associated with cellulose.

Key Achievements

-

Cloning of the part encoding Cerberus

-

Production of Cerberus

-

Functionalisation of cellulose

Materials and Methods

The fusion between the streptavidin linker and the CBM3a domain sequences followed by the amber stop codon was cloned into the pET28 expression vector in fusion with the His-tag. The resulting construct was co-transformed into E. coli strain with the pEVOL expression vector. The latter allows to the expression of the amino acyl tRNA synthetase aaRS. In presence of AzF, this enzyme synthesizes the orthogonal AzF-tRNA for in vivo AzF incorporation in place of amber Stop codon. The Cerberus platform was produced by adding IPTG (Cerberus induction), L-arabinose (amino acyl tRNA synthetase production), and AzF to the medium. The His-tagged protein was then purified on IMAC resin charged with cobalt and used in cellulose pull down assays. For the experimental details, see experiments page.

Results and Discussion

Production and purification of Cerberus

Cerberus production requires a deferred induction. We first induced the synthesis of aarS/tRNA pair with L-arabinose, and added AzF at the same time. One hour later, we induced the production of Cerberus with IPTG.

Cerberus production and purification were analysed on SDS gel (Figure 2). Induction in the presence of AzF (Figure 2, lane I+AzF) led to the expression of two major bands at 37 and 39 kDa approximately compared to control conditions, namely the non-induced (lane NI) and induced without AzF (lane I-AzF). We hypothesized that the upper band would correspond to Cerberus (expected molecular weight of Cerberus with monomeric streptavidin: 41 kDa) and the lower bands to the Orthos proteins (Cerberus without the AzF and the His-tag). Surprisingly, both bands were present in the elution fractions which is incoherent since Orthos lacks an His-tag and was supposed to be washed out during purification steps. To confirm our hypothesis, we analysed the same fractions by western blot using antibodies detecting the His-tag (Figure 3).

Anti-His-tag antibodies revealed a band at about 45 kDa in the sample corresponding to IPTG induction in the presence of AzF (Figure 3, lane I+AzF). This band is not present in control samples (Figure 3, lane NI and I-AzF), indicating that it corresponds to the Cerberus protein (theoretical size: 41 kDa). In addition to the full length protein, we observed several extra bands which very likely correspond to proteolysis products since they are detected with the anti-His-tag antibodies. Moreover, the band at 45 kDa is clearly detected in elution samples (Figure 3, lanes E). The band at 37 kDa observed on the SDS PAGE (Figure 2) is not observed on the Western blot. These results show that the experimental setup to produce Cerberus is also likely leading to the production of Orthos when the amber stop codon is not recognized by the AzF-charged orthogonal tRNA. Although Orthos does not contain a His-tag at its C-terminus, the protein seems to be efficiently co-purified with Cerberus. The basis of this observation is unclear but it may suggest that Orthos and Cerberus interact with each other, via their CBM3 or streptavidin moieties.

We estimated that the purification level of Cerberus with monomeric streptavidin in the elution samples was about 62%. These data show that Cerberus was efficiently purified and can be used for pull down assays.

Validation

Validation using FITC (Fluorescein isothiocyanate) molecules

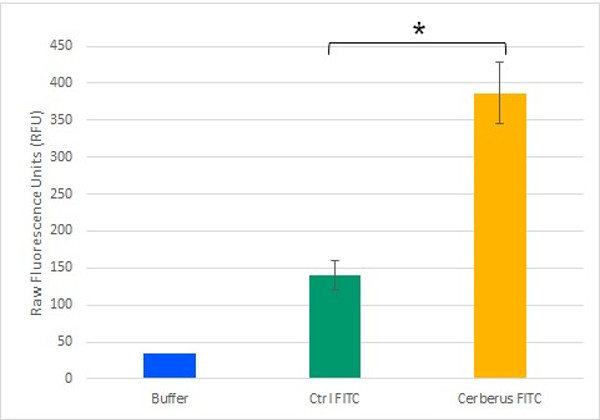

To test the potential of Cerberus in functionalising cellulose, we monitored its ability to mediate an interaction between cellulose and a fluorescent compound. To generate a fluorescently labelled Cerberus protein, we performed a SPAAC reaction on 3.2 µM Cerberus protein using 31.9 µM of FITC-DBCO. In control experiment, 31.9 µM of FITC alone was used. These samples were then incubated with cellulose and after five washes with Tris-HCl buffer, fluorescence levels were measured in the cellulose pellet fractions (Figure 9). We observed that the fluorescence levels in the cellulose pellet incubated with Cerberus protein clicked to FITC were about 3 times higher than in the control experiments corresponding to the cellulose pellet incubated with FITC alone. These results show that Cerberus can efficiently be conjugated to fluorescent molecules bearing a DBCO group by click chemistry and that the resulting fluorescent molecules strongly interact with cellulose. Therefore, Cerberus is both a convenient and potent platform to functionalise cellulose.

Validation using paramagnetic beads

We further characterize the functionality of Cerberus in a second set of experiments using paramagnetic beads. To bind paramagnetic beads to Cerberus, we performed a click reaction using 3.2 µM of Cerberus protein and 32 µM DBCO-conjugated paramagnetic beads. As a control experiment, 32 µM of paramagnetic beads were used. These samples were then incubated with cellulose, and after five washes with Tris-HCl buffer, we measured the magnetisation of cellulose using a magnet.

As observed on the video (Figure 5), the cellulose incubated with the Cerberus protein conjugated to paramagnetic beads is quickly and totally attracted by the magnet. In contrast, in the control experiment, no clear movement towards the magnet was observed.

These results show that Cerberus has the ability to interact simultaneously with cellulose and molecules with a DBCO group, confirming that the Cerberus platform allows to functionalise cellulose through its linker containing unnatural amino acid.

Towards other functionalisations

To go further in our project, we decided to functionalise two inorganic molecules, graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNT), using a reaction of diazotization. This experiment was performed with the help of the ENSIACET laboratory in Toulouse. To check functionalisation, we analysed samples by Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). The concept of TGA consists of measuring the mass change of a sample depending on temperature and time, in a controlled atmosphere. We chose to perform the experiment under nitrogen, N2, an inert gas that avoids mass loss by oxidation, and we studied the mass change from 25 to 1,000 °C (15 °C/min).

Figures 6 and 7 present the results of mass loss for non-activated Carbon Nanotube (CNT) and activated CNT samples, respectively. For activated CNT sample (Figure 7), we observed a mass loss of 27.4% around 100 °C corresponding to water loss. A second step of mass loss is observed around 550 °C, with a diminution of 19.8%. For the non-activated sample (Figure 6), we observed two mass losses at 150 and 750 °C corresponding to 1.5% and 3% of mass loss respectively. The significative difference between these two samples allowed us to conclude that the CNT activation has been successful.

Figures 8 and 9 present the results of mass loss for non-activated graphene and activated graphene samples respectively. For activated graphene sample (Figure 9), we observed a mass loss of 31.0% around 100 °C corresponding to water loss. A second step of mass loss is observed around 500 °C, with a diminution of 19.0%. For the non-activated sample (Figure 8), we did not observe a significative mass loss. So we can conclude that the graphene activation has been successful.

Our initial plan was to functionalise cellulose with CNT and graphene in order to change cellulose fibre rigidity and create conductive cellulose, respectively. Unfortunately, we did not have enough time during the course of the iGEM competition to complete these tests. Given the success of the other functionalisation, we have reasonable hopes that these experiments will be successful too.

Perspectives

Our experiments provide robust proofs of concept that Cerberus can be conjugated, via its unnatural amino acid AzF, to organic or inorganic molecules bearing a DBCO group by click chemistry. The resulting molecules strongly interact with cellulose and are therefore potent cellulose functionalising compounds.

We can now consider fixation of various compounds that can be chemically functionalised. We can also imagine double fixations, for example a fluorophore on the streptavidin head and paramagnetic beads on the AzF linker. This double fixation allows us to envision endless possibilities to functionalise cellulose (see Demonstrate).

Bacterial Cellulose production and functionalisation

Background

Our ultimate dream was to be able to produce functionalised cellulose in vivo. Some microorganisms naturally produce cellulose. One of these, Gluconacetobacter hansenii, can produce cellulose as a biofilm to protect itself. We took advantage of the work of iGEM Imperial team 2014 who set up culture conditions to optimize cellulose production. Our challenge was to assess if our technology is compatible with bacterial cellulose as a first step before producing functionalised cellulose in vivo.

Key Achievements

-

Production of about 100g of dried bacterial cellulose

-

Functionalisation of bacterial cellulose with Sirius

Materials and Methods

G. hansenii was grown in Hestrin-Shramm (HS) medium at 30 °C. After one week of culture, bacterial cellulose was extracted and purified. For the experimental details, see our experiments page.

For the functionalisation, bacterial cellulose was incubated with purified Sirius (CBM3a-mRFP1) or with purified mRFP1 alone as a control. Cellulose was then washed about 10 times with Tris-HCl buffer buffer to remove non-attached proteins.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1a presents the results of the functionalisation of our bacterial cellulose with the Sirius fluorescent protein. Only the cellulose sample incubated with Sirius kept the color after several washes with resuspension buffer. Likewise fluorescence remained associated to cellulose only for Sirius (Figure 1b). These results show that CBM3a can interact with the bacterial cellulose and allows fixation of the mRFP1 protein to cellulose.

Perspectives

Now that we have proved the capacity of CBM3a to interact with bacterial cellulose, we are confident that Orthos and Cerberus proteins should also interact with bacterial cellulose. Now the next step will be to produce functionalised bacterial cellulose in vivo . For this, we had planned to produce the Cerberus platform in the yeast Pichia pastoris because of its secretion capacity. Indeed, our idea was to co-culture both strains in the same reactor in order to produce functionalised cellulose in vivo. This work on P. pastoris was performed at the same time as our attempt in E. coli but has not been as successful. We managed to produce the Orthos protein in the yeast but we never succeeded in producing Sirius and we never got the plasmid needed to produce the tRNA synthetase necessary for AzF incorporation in P. pastoris. In addition, the production of Orthos in the yeast was very low and not sufficient to conduct our assays. So production of functionalised cellulose in vivo will require improving the P. pastoris part of our project.

No dogs were harmed over the course of this iGEM project.

The whole Toulouse INSA-UPS team wants to thank our sponsors, especially:

And many more. For futher information about our sponsors, please consult our Sponsors page.

The content provided on this website is the fruit of the work of the Toulouse INSA-UPS iGEM Team. As a deliverable for the iGEM Competition, it falls under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. Thus, all content on this wiki is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (or any later version). For futher information, please consult the official website of Creative Commons.

This website was designed with Bootstrap (4.1.3). Bootstrap is a front-end library of component for html, css and javascript. It relies on both Popper and jQuery. For further information, please consult the official website of Bootstrap.