Tugbainanc (Talk | contribs) |

Tugbainanc (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

| − | |||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 358: | Line 357: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 00:52, 16 October 2018

Project Design

Background

What are furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural?

Figure 1: Chemical structure of furfural

Figure 1: Chemical structure of furfural

Figure 2: Chemical structure of 5-HMF

Figure 2: Chemical structure of 5-HMF

Furfural is an inhibitory by-product formed by the dehydration of pentose sugars during dilute acid pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass (Kumar & Sharma, 2017).

A corresponding compound, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF), is formed of hexose sugars such as glucose and fructose (Kumar & Sharma, 2017; Wang et al., 2012).

These toxic furans are known to suppress cell growth, decrease ethanol yield, cause damages in the cell DNA and harm many enzymes during glycolysis, therefore, pose a great danger to the convenience of lignocellulosic ethanol production (Ask et al., 2013). These toxins are proven to affect not only E.coli KO11 that was used in our project but also other ethanologenic organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae a strain of yeast, which is widely used in fermentation. (Wang et al., 2012; Almeida et al., 2007; Ask et al., 2013).

Moreover, the addition of furfural to hemicellulose hydrolysates has been shown to restore toxicity (Wang et al., 2011). Furfural is, hence, unique in potentiating the toxicity of other compounds unlike various hydrolysate inhibitors, hindering the bioethanol production drastically (Wang et al., 2012).

Our solution: Simultaneous expression of FucO and GSH

FucO :L-1,2-Propanediol Oxidoreductase

Our first solution, NADH-dependent propanediol oxidoreductase (FucO) has been seen to reduce the amount of furfural output as it increases the furfural tolerance by 50% and permits the fermentation of 15 mM furfural. FucO, basically, is the gene responsible for the production of L-1,2-propanediol oxidoreductase which is an enzyme that converts furans; HMF and furfural, to non-toxic alcohols without interfering with the NADPH metabolism.

This is crucial as when furfural is present in the field, the organism’s automatic expression of oxidoreductases go active, such as YqhD and FucO. However, the problem is that, YqhD has the priority to be synthesized which is NADPH-dependent.

This suggest that YqhD will also have detrimental effects on the growth and living of the bacteria as it will compete with the biosynthesis of NADPH during fermentation in E.coli (Zheng, 2013). The native conversion of NADH to NADPH in E. coli is already insufficient to revitalize the NADPH pool during fermentation, so the actions shouldn’t be interfering with NADPH metabolism (Wang et al., 2011; 2012).

Thus, when FucO is overexpressed, the organism’s need to express NADPH dependent oxidoreductases is decreased, providing the cell a sustainable intracellular environment.

Figure 3: Possible reaction pathways for furfural hydrogenation

Figure 3: Possible reaction pathways for furfural hydrogenation

GSH: Bifunctional gamma-glutamate-cysteine ligase/Glutathione synthetase

In normal circumstances, simultaneous detoxification of ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species), the conversion of HMF and furfural drag the cell into a more oxidized intracellular environment and deteriorate the antioxidant defense system of the cell (Ask et al., 2013). Here, increasing the cellular levels of antioxidants are essential.

In our case the expression of glutathione (GSH) stands the best chance, as it is the master antioxidant in living organisms coping with ROS, oxidative stress and increasing furan tolerance (Kim & Hahn, 2013; Höck et al., 2013).

Additionally, a GSH derivative, glutathione S-transferase, reacts with a number of harmful chemical species; such as ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and xenobiotics including environmental carcinogens (Dasari et al., 2017).

In consideration of these studies, we have come to the conclusion that, the concurrent overexpression of GSH and FucO would increase cellular growth rates, lifespan and ethanol production yield (Ask et al., 2013).

The Working Principle of Our Parts:

The strong promoter we used, BBa_J23100, is active depending on the availability of RNA polymerase holoenzyme as it is a member of the constitutive promoter family. Our bacterial ribosome binds to the strong ribosome binding site from the community collection, BBa_BOO34.

Figure 4: Representation of our gene circuit.

Figure 4: Representation of our gene circuit.

The first protein coding region we have, placed after the RBS, FucO, codes for L-1,2-propanediol oxidoreductase (a homodimer enzyme) in order to act upon furfural presence in the field (Zheng, 2013). The metabolism of furfural by NADH-dependent oxidoreductases reduces the toxicity of the chemical by turning it into furfuryl alcohol, a derivative (Zheng, 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Allen et al., 2010).

Our second protein coding region (GSH), codes for bifunctional gamma-glutamate-cysteine ligase/glutathione synthetase which is composed of a non-protein thiol group, and a tripeptide: cysteine, glycine and glutamic acid (Lu, 2013).

GSH is usually found in the thiol-reduced form in living organisms which is crucial for the detoxification of reactive oxygen species and the other free radicals (Ask et al., 2013).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are harmful substances that alter protein based matters by interacting with their electrons as themselves have an unbalanced electron state (Lu, 2013; Burton & Jauniaux, 2011). Because many benefits of GSH include scavenging of ROS, protection against endogenous toxic metabolites and detoxification of xenobiotics, we chose this gene to include in our bacteria (Höck et al., 2013).

Our Experimental Plan to Test Our Parts:

We designed biochemical assays in order to evaluate the effects of our circuits on life span of bacteria, cell mass, and ultimately bioethanol yield

Figure 5: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 1.

Figure 5: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 1.

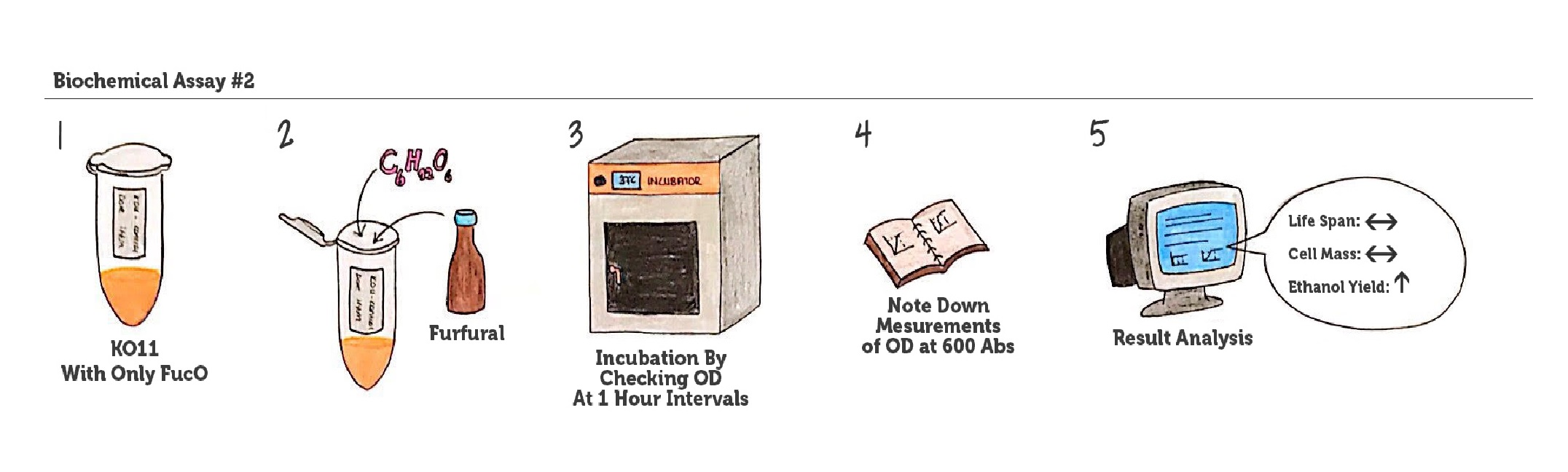

Figure 6: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 2.

Figure 6: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 2.

Figure 7: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 3.

Figure 7: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 3.

Figure 8: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 4.

Figure 8: Representation of our experimental plan/ assay no. 4.

In the assay, step by step:

First, cultures of KO11 are grown in 4 groups:

#1: KO11 control group (non-engineered: without gene insertion)

#2: KO11 containing only FucO as insert

#3: KO11 containing only GSH as insert

#4: KO11 containing both GSH and FucO

With the experiment groups above, the steps (below) of our biochemical assay has been applied and we have compared the results.

- Secondly, in order to set our experiments to fermentation processes done in real-life, glucose is added to the medium. In biorefineries, glucose is obtained from the pretreatment methods, specifically dilute acid pretreatment.

- Then, the bacteria are exposed to toxic furfural, which is the main byproduct that occurs in the pretreatment process.

- At this point, real life pretreatment and fermentation conditions are supplied and in order to make a comparison in terms of the difference our genes create. Then, they are placed in incubation and OD measurements at Abs 600 at 1-hour intervals are obtained.

We can conclude that if the bacteria have an increased tolerance to ROS and furans, causing higher OD values will indicate that the bacteria have gained higher cell mass and thus, the ethanol yield will automatically increase.

As of our hypothesis, we expected to see the best ethanol yield, the longest lifespan and the greatest cell mass in group #4 (assay no. 4) since the KO11 would carry the best qualities in terms of genes. Of course; the least ethanol yield, cell mass, and the shortest lifespan would be observed in group #1 (assay no. 1) since it is the un-engineered KO11 strain of E.coli that is intolerant to byproducts.

Apart from the biochemical assay we conducted in which we’ve seen bacteria growth and OD differentiations, we’ve also reached an expert involved in ethanol production from KO11 strain of E.coli. We’ve sent her bacteria samples from four of our experiment groups and she helped us test the bioethanol production of them to have a comparative analysis.

For the fermentation processes, pressed and dried quince pomace that is composed of 28.8% glucose, 55.7% fructose and 10.1% sucrose based on dry mass was used instead of glucose (Deniz et al. 2015). After quince pomace and LB were mixed aseptically, fermentation was carried out at pH 6 with automatic KOH additions in the field to avoid pH levels lower than 6. Solids were separated via centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 min at 5°C and supernatant was used to calculate ethanol and reduced sugar. (Deniz et al. 2015)

Total soluble reducing sugar content of quince pomace was obtained by dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method in which absorbance was measured at 540 nm and ethanol concentrations of test groups were determined by using a Gas Chromatograph. (Deniz et al. 2015)

How our parts would work in different systems?

By modifying E. coli strain KO11, we have actually designed bacteria that can cope with reactive oxygen species, free radicals and furan byproducts without interfering with the NADPH metabolism (Höck et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011).

Thus, our parts would be also feasible in other conditions in which toxins such as ROS or inhibitors such as heavy metals exist (Ask et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011). This genetical improvement is due to GSH, which is an antioxidant that detoxifies free radicals and such types; and FucO which is an oxidoreductase that transforms HMF and furfural to non-toxic alcohols without getting in the way of the bacteria’s own metabolism (Ask et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011).

Although these two genes highly contribute to systems on their own; for a more efficient production of bioethanol and bacteria with higher tolerance, such systems and mechanisms are in need of them both at the same time. This is an inference from the fact that an increase in GSH enhances tolerance to furfural but not to 5-HMF, while FucO on the other hand, is in need of GSH as it provides a longer lifespan and deals with the interactions of radicals (Kim & Hahn, 2013).

- Allen, S. A., Clark, W., McCaffery, J. M., Cai, Z., Lanctot, A., Slininger, P. J., … Gorsich, S. W. (2010). Furfural induces reactive oxygen species accumulation and cellular damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 3, 2. http://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-3-2

- Almeida, J, R,. Modig, T., Petersson, A., Hahn-Hagerdal, B., Liden, G., Gorwa-Grauslund, M, F., (2007). Increased tolerance and conversion of inhibitors in lignocellulosic hydrolysates by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. Vol: 82,4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.1676

- Ask, M., Bettiga, M., Mapelli, V., Olsson, L. (2013). The influence of HMF and furfural on redox-balance and energy-state of xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-22

- Ask, M., Mapelli, V., Höck, H., Olsson, L., Bettiga, M. (2013). Engineering glutathione biosynthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae increases robustness to inhibitors in pretreated lignocellulosic materials. Microbial Cell Factories. 12:87 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3817835/

- Burton, G. J., & Jauniaux, E. (2011). Oxidative stress. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 25(3), 287–299. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.10.016

- Dasari, S., Ganjayi, M.S., Origanti, L., Balaji, H., Meriga, B. (2017). Glutathione S-transferases Detoxify Endogenous and Exogenous Toxic Agents- Minireview. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/901b/a8c5eab4904637cc31b32b955f2a1df6821d.pdf

- Deniz, I., Imamoglu, E., Sukan, F., V., (2015). Evaluation of scale-up parameters of bioethanol production from Escherichia coli KO11. Turkish Journal of Biochemistry. Vol 40, no 1, 74-80. Retrieved from: http://www.turkjbiochem.com/2015/074-080.pdf

- Fuente-Hernandez, A., Lee, R., Beland, N., Zamboni, I., Lavoie, J.M. (2017). Reduction of Furfural to Furfuryl Alcohol in Liquid Phase over a Biochar-Supported Platinum Catalyst. Energies. 10(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/en10030286

- Höck, H., Ask, M., Mapelli, V., Olsson, L., Bettiga, M. (2013). Engineering glutathione biosynthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae increases robustness to inhibitors in pretreated lignocellulosic materials. Microbial Cell Factories. 12:87 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3817835/

- Kim, D., & Hahn, J.-S. (2013). Roles of the Yap1 Transcription Factor and Antioxidants in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae’s Tolerance to Furfural and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, Which Function as Thiol-Reactive Electrophiles Generating Oxidative Stress. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79(16), 5069–5077. http://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00643-13

- Kumar, A. K., & Sharma, S. (2017). Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: a review. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, 4(1), 7. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-017-0137-9

- Lu, S. C. (2013). Glutathione Synthesis. Biochemica et Biophysica Acta, 1830(5), 3143–3153. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID=7362, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/7362 (accessed Aug. 7, 2018).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID=237332, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/237332 (accessed Aug. 7, 2018).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID=7361, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/7361 (accessed Aug. 9, 2018).

- ResearchGate, (2014), Scanning Electron Microscopy Image of Saccharomyces. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Scanning-electron-microscopy-image-of-Saccharomyces-cerevisiae-The-budding-yeast-cells_fig1_308144762

- Wang, X., Miller, E. N., Yomano, L. P., Zhang, X., Shanmugam, K. T., & Ingram, L. O. (2011). Increased Furfural Tolerance Due to Overexpression of NADH-Dependent Oxidoreductase FucO in Escherichia coli Strains Engineered for the Production of Ethanol and Lactate. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(15), 5132–5140. http://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.05008-11

- Wang, X., Miller, E. N., Yomano, L.P., Shanmugam, K. T. & Ingram, L.O (2012). Cryptic ucpA gene increases furan-tolerance in Escherichia coli, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, Volume 78, Issue 7, http://aem.asm.org/content/early/2012/01/18/AEM.07783-11.short

- Zheng, H., Wang, X., Yomano, L.P., Geddes, R. D., Shanmugan, K. T., Ingram, L.O. (2013). Improving Escherichia coli FucO for Furfural Tolerance by Saturation Mutagenesis of Individual Amino Acid Positions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Vol 79, no 10. 3202–3208. http://aem.asm.org/content/79/10/3202.full.pdf+html