| (29 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

<div class="parentContent"> | <div class="parentContent"> | ||

| − | <div class="sidenav" style='padding-top: | + | <div class="sidenav" style='padding-top: 250px;' > |

<a href="#1">Bioassay Design</a> | <a href="#1">Bioassay Design</a> | ||

<a href="#2">Promoter Constructs</a> | <a href="#2">Promoter Constructs</a> | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

<a href="#6">Measurement</a> | <a href="#6">Measurement</a> | ||

<a href="#7">Extensions</a> | <a href="#7">Extensions</a> | ||

| − | <a href="#8">References</a> | + | <a href="#8">Project Design Notebook</a> |

| + | <a href="#9">References</a> | ||

| Line 104: | Line 105: | ||

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | We designed a mammalian cell-based bioassay that reports activation of specific stress pathways via fluorescence, for use in environmental toxicology. To do this, we selected transcriptionally regulated target genes which are present in mammalian cells and are involved in stress pathways. We isolated the promoters with transcription factor binding sites from these target genes and coupled them to a fluorescent reporter gene. We selected EGFP, a variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP is ubiquitous in synthetic biology due to its reliability and ease of measurement [1]. EGFP is derived from GFP | + | We designed a mammalian cell-based bioassay that reports activation of specific stress pathways via fluorescence, for use in environmental toxicology. To do this, we selected transcriptionally regulated target genes which are present in mammalian cells and are involved in stress pathways. We isolated the promoters with transcription factor binding sites from these target genes and coupled them to a fluorescent reporter gene. We selected EGFP, a variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP is ubiquitous in synthetic biology due to its reliability and ease of measurement [1]. EGFP is derived from GFP and has been optimized for use in mammalian systems. When a chemical of concern is screened using our assay, if it triggers a specific stress response, the reporter gene will be expressed, causing the assay to fluoresce. The fluorescence of the assay can be quantitatively measured and analyzed. This assay will provide data on the effect of chemicals of concern on the physiological health of mammalian cells; measurements may be easily taken a range of concentrations, duration of exposure, salinities, pH, temperatures, nutrient availabilities, and other conditions. This also allows for measurement of synergistic or interfering effects due to multiple chemicals of concern present simultaneously. |

| − | <p>We selected 8 promoter constructs derived from 5 target genes (see Figure 1 below) and coupled them to EGFP. This promoter and reporter gene construct | + | <p>We selected 8 promoter constructs derived from 5 target genes (see Figure 1 below) and coupled them to EGFP. This promoter and reporter gene construct were inserted into a plasmid and transfected into two cell lines (see Figure 2 below). The resulting bioassays were exposed to different chemicals of concern at a variety of concentrations and conditions (see Figure 3 below). |

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 112: | Line 113: | ||

<div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why not use whole organisms?</i></b></div> | <div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why not use whole organisms?</i></b></div> | ||

| − | <div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'>A cell-based approach cannot replace in vivo toxicology studies. However these studies require extensive funding, time, and other resources. By developing a relatively low-cost, cell-based bioassay, preliminary data may be quickly gathered, allowing for more informed decision making as to which in vivo studies are necessary. By using a cell-based preliminary assay, it is our hope that researchers will be able to quickly gather data, make more informed decisions, and save resources. Our cell-based bioassay may also be used to add to the body of knowledge concerning the effect of specific chemicals of concern on the physiological health of mammalian cells and the mechanism of stress. </div> | + | <div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'>A cell-based approach cannot replace in vivo toxicology studies. However, these studies require extensive funding, time, and other resources. By developing a relatively low-cost, cell-based bioassay, preliminary data may be quickly gathered, allowing for more informed decision making as to which in vivo studies are necessary. By using a cell-based preliminary assay, it is our hope that researchers will be able to quickly gather data, make more informed decisions, and save resources. Our cell-based bioassay may also be used to add to the body of knowledge concerning the effect of specific chemicals of concern on the physiological health of mammalian cells and the mechanism of stress. </div> |

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why not use cell-free biochemical assays, such as ELISA?</i></b></div> | <div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why not use cell-free biochemical assays, such as ELISA?</i></b></div> | ||

| Line 123: | Line 124: | ||

<div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | The goal of our bioassay is to create a tool that can be used to better understand the effect on the physiological health of mammalian cells of environmental toxins. An alternative way to achieve this knowledge is to expose cells to the chemicals of concern, lyse the cells, isolate the RNA, and run a quantitative-real-time-reverse-transcription-PCR in order to characterize and quantify the mRNAs present in the cell. However, this approach has limitations. It | + | The goal of our bioassay is to create a tool that can be used to better understand the effect on the physiological health of mammalian cells of environmental toxins. An alternative way to achieve this knowledge is to expose cells to the chemicals of concern, lyse the cells, isolate the RNA, and run a quantitative-real-time-reverse-transcription-PCR in order to characterize and quantify the mRNAs present in the cell. However, this approach has limitations. It requires lysing the cells and cannot be used to gather real-time data about the behavior of the same cell over time. By using a fluorescent reporter gene, we can measure the induction of the reporter gene over time without lysing cells and can more easily take a large number of data points across different chemicals of concern, concentrations, and other variables. A fluorescent bioassay also reduces the amount of work required to measure many data points, compared to PCR based methods. Our bioassay also makes possible the future study of the behavior of a single cell over time after exposure to a chemical of concern, with the aid of microfluidics. |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why use mammalian cells?</i></b></div> | <div style = 'padding-left:10%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 20px; color: #d9a900'; ><b><i>Why use mammalian cells?</i></b></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:10%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | We chose to use mammalian cells because they make much more accurate models for human health than bacteria or yeast. Furthermore, within the iGEM competition and the field of synthetic biology as a whole, there has been relatively little work with mammalian systems, compared to bacteria, yeast, and algae. Working with mammalian cells brings a variety of new challenges and opportunities to iGEM: they are more difficult and expensive to culture than bacteria, they require specialized equipment and safety training, they can be used to produce proteins suitable for use in human therapeutics (due to similar | + | We chose to use mammalian cells because they make much more accurate models for human health than bacteria or yeast. Furthermore, within the iGEM competition and the field of synthetic biology as a whole, there has been relatively little work with mammalian systems, compared to bacteria, yeast, and algae. Working with mammalian cells brings a variety of new challenges and opportunities to iGEM: they are more difficult and expensive to culture than bacteria, they require specialized equipment and safety training, they can be used to produce proteins suitable for use in human therapeutics (due to similar post-translational modifications), and they can be used for more complicated circuits and pathways utilizing spatial/temporal differentiation [3]. |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 141: | Line 142: | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | + | Table 1 shows the promoter constructs we used and the target genes from which they were derived. Full FASTA sequences for our promoters are available <a href= "https://2018.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/SupplementalMaterials">here.</a> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | <div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | ||

| − | + | Table 1. Promoter Constructs | |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 171: | Line 172: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">305 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">305 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[4]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 179: | Line 180: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">377 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">377 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[5]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 187: | Line 188: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">59 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">59 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[5]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 195: | Line 196: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 5’ end</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 5’ end</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[5]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 203: | Line 204: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Oxidative, heavy metal</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 3’ end</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 3’ end</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[5]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 211: | Line 212: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Unfolded protein response (UPR), endoplasmic reticulum stress</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Unfolded protein response (UPR), endoplasmic reticulum stress</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">695 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">695 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[6]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 219: | Line 220: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Organochlorine biocides, genotoxins</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Organochlorine biocides, genotoxins</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">811 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">811 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[7], [8]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 227: | Line 228: | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">Genotoxins, mechanical stress</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">Genotoxins, mechanical stress</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">1006 nucleotides</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">1006 nucleotides</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">[ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">[9]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| Line 237: | Line 238: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | <div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | ||

| − | + | Table 2. Host Strains | |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 257: | Line 258: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">CHO-DG44</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">CHO-DG44</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">An immortal, adherent cell line derived from | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">An immortal, adherent cell line derived from Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus) ovary cells. The strain we used is dihydrofolate reductase deficient.</td> |

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">ATCC: CRL-9096 [ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">ATCC: CRL-9096 [10]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">AML-12</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">AML-12</td> | ||

<td class="tg-yw4l">An immortal, adherent cell line derived from mouse (Mus musculus) liver cells.</td> | <td class="tg-yw4l">An immortal, adherent cell line derived from mouse (Mus musculus) liver cells.</td> | ||

| − | <td class="tg-yw4l">ATCC: CRL-2254 [ | + | <td class="tg-yw4l">ATCC: CRL-2254 [11]</td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| Line 273: | Line 274: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | <div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | ||

| − | + | Table 3. Chemicals of Concern | |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<style type="text/css"> | <style type="text/css"> | ||

| − | + | .tg {border-collapse:collapse;border-spacing:0;} | |

| − | + | .tg td{font-family:Arial, sans-serif;font-size:14px;padding:10px 5px;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;overflow:hidden;word-break:normal;border-color:black;} | |

| − | + | .tg th{font-family:Arial, sans-serif;font-size:14px;font-weight:normal;padding:10px 5px;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;overflow:hidden;word-break:normal;border-color:black;} | |

| − | + | .tg .tg-j2xt{font-weight:bold;border-color:#002855;text-align:left;vertical-align:top} | |

| − | + | .tg .tg-0lax{text-align:left;vertical-align:top} | |

| − | + | </style> | |

| − | + | <table class="tg"> | |

| − | <tr> | + | <tr> |

| − | + | <th class="tg-j2xt">Chemical name</th> | |

| − | + | <th class="tg-j2xt">Occupational limit</th> | |

| − | + | <th class="tg-j2xt">LD50</th> | |

| − | </ | + | <th class="tg-j2xt">Klamath Environmental concentration</th> |

| − | <tr> | + | <th class="tg-j2xt">Cytotoxicology (In micromoles per liter)</th> |

| − | <td class="tg- | + | </tr> |

| − | + | <tr> | |

| − | </ | + | <td class="tg-0lax">Hydrogen Peroxide</td> |

| − | <tr> | + | <td class="tg-0lax">75 mg/L</td> |

| − | <td class="tg- | + | <td class="tg-0lax">2000 mg/kg</td> |

| − | + | <td class="tg-0lax">--</td> | |

| − | </ | + | <td class="tg-0lax">Relevant dose is 60 uM</td> |

| − | <tr> | + | </tr> |

| − | <td class="tg- | + | <tr> |

| − | + | <td class="tg-0lax">Warfarin</td> | |

| − | </ | + | <td class="tg-0lax">0.1 ug/L</td> |

| − | <tr> | + | <td class="tg-0lax">374 mg/kgmice186 mg/kg rats</td> |

| − | <td class="tg- | + | <td class="tg-0lax">Qualitatively detected by Tom Young’s lab; unpublished data</td> |

| − | + | <td class="tg-0lax">Relevant dose is 0.0316 – 31.6 μM</td> | |

| − | </ | + | </tr> |

| − | <tr> | + | <tr> |

| − | <td class="tg- | + | <td class="tg-0lax">2,4-D</td> |

| − | + | <td class="tg-0lax">10 ug/L</td> | |

| − | </tr> | + | <td class="tg-0lax">2019 ppm (min)12979 ppm(max)</td> |

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">0.424 - 7.49 ppm</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">-</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">Copper sulfate</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">1 ppb by inhalation</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">30 mg/kg</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">Copper measured at concentration of 19-67 ppm (112uM - 420uM)</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">Relevant dose is & lt;1.3ppm (6.25uM)</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">Metam Sodium</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">Limit of irritation 22 ug/L</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">781 mg/kg (rat)1836 ppm (min)</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">131309.21 kg</td> | ||

| + | <td class="tg-0lax">-</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| Line 317: | Line 335: | ||

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | We used pcDNA3-EGFP as our plasmid [ | + | We used pcDNA3-EGFP as our plasmid [12]. The original plasmid is shown in Figure 1 below. |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 323: | Line 341: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | <div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | ||

| − | Figure | + | Figure 1. Map of pcDNA3-EGFP [13] |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| Line 330: | Line 348: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | To prepare our constructs, we used restriction enzymes to remove the CMV enhancer, CMV promoter, and the T7 promoter. Promoter sequences were inserted using either restriction digest or Sequence and Ligation Independent Cloning (SLIC). Figure | + | To prepare our constructs, we used restriction enzymes to remove the CMV enhancer, CMV promoter, and the T7 promoter. Promoter sequences were inserted using either restriction digest or Sequence and Ligation Independent Cloning (SLIC). Figure 2 below shows the complete plasmid for construct MT2_1. |

</div> | </div> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | <div style = 'line-height: 25px' > | ||

| − | Figure | + | Figure 2. Map of pcDNA-EGFP_MT2_2 [13] |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| Line 347: | Line 365: | ||

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | Our bioassay was constructed on 96 well plates. Plates were seeded with 30,000 cells/well for AML12 cells and 20,000 cells/well for CHO cells and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. The cells were seeded such that 24 hours after reaching they would be at 70%-90% confluence. At this time, we transfected our cells with the target promoter and allowed to sit for another 24 hours. Next, the complete growth media present in the wells were aspirated and replaced with clear media containing chemical of concern. | + | Our bioassay was constructed on 96 well plates. Plates were seeded with 30,000 cells/well for AML12 cells and 20,000 cells/well for CHO cells and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. The cells were seeded such that 24 hours after reaching they would be at 70%-90% confluence. At this time, we transfected our cells with the construct containing the target promoter with reporter gene and allowed to sit for another 24 hours. Next, the complete growth media present in the wells were aspirated and replaced with clear media containing chemical of concern. We experimented with use of both a Tecan plate reader and a fluorescent microscope for measurement. For a full report on our measurement practices, please visit our <a style ='color: #d9a900;' href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/Measurement">measurement page</a> and our <a style ='color: #d9a900;' href="https://2018.igem.org/Team:UC_Davis/Experiments">experiments page.</a> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 354: | Line 372: | ||

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| − | Our project opens up new opportunities for work with mammalian cells in the iGEM competition. By adding new mammalian parts to the registry, future teams will have the ability to easily access useful mammalian regulatory elements for use in their own constructs. Future teams may also benefit from our protocol for measuring fluorescence of adherent mammalian cells. One extension of our work is to transfect our construct into human cell lines. By using human cells, the bioassay will be a more accurate model for human health. | + | Our project opens up new opportunities for work with mammalian cells in the iGEM competition. We have created comprehensive protocols for working with two mammalian cell lines, AML-12, and CHO-DG44, which may be downloaded on our Experiments Page. By adding new mammalian parts to the registry, future teams will have the ability to easily access useful mammalian regulatory elements for use in their own constructs. Future teams may also benefit from our protocol for measuring fluorescence of adherent mammalian cells. One extension of our work is to transfect our construct into human cell lines. By using human cells, the bioassay will be a more accurate model for human health. |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | <div style = 'padding-top:100px;padding-bottom: 60px; font-size: 30px; color: #d9a900'; ><b>Project Design Notebook </b></div> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Project Design Notebook available for download below contains our thought and research as well as work space, as we designed our project. Within, we grapple with aspects of human practices, molecular biology, environmental toxicology, and the logistics of planning our experiments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style='padding-top: 20px;'></div> | ||

| + | <div id="8" style = 'padding-left:7%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 25px; color: #667d9d'; ><b>Project Design Notebook</b></div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | <embed src= "https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/5/55/T--UC_Davis--PDN.pdf" width= "600" height= "500" style ='border-width: 3px;border-color: gray;'> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style='padding-top: 50px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-top: 20px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 20px;'></div> | ||

| − | <div id=" | + | <div id="9" style = 'padding-left:7%;padding-bottom: 22px; font-size: 25px; color: #667d9d'; ><b>References</b></div> |

<div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 10px;'></div> | ||

<div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | <div style='padding-left:7%;padding-right: 7%'> | ||

| Line 367: | Line 402: | ||

Clinical Chemistry Dec 2005, 51 (12) 2415-2418; DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051532 | Clinical Chemistry Dec 2005, 51 (12) 2415-2418; DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051532 | ||

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [3] | + | [3]Kis Z, Pereira HSA, Homma T, Pedrigi RM, Krams R. 2015 Mammalian synthetic biology: emerging medical applications. J. R. Soc. Interface 12 : 20141000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.1000 |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [4] | + | [4] Larochelle, Olivier & Labbé, Simon & Harrisson, Jean-François & Simard, Carl & Tremblay, Véronique & St-Gelais, Geneviève & Govindan, Manjapra Variath & Seguin, Carl. (2008). Nuclear Factor-1 and Metal Transcription Factor-1 Synergistically Activate the Mouse Metallothionein-1 Gene in Response to Metal Ions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 283. 8190-201. 10.1074/jbc.M800640200. |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | + | [5] Santos, Anderson K. et al. "Expression System Based on An MtIIa Promoter to Produce Hpsa In Mammalian Cell Cultures". Frontiers in Microbiology, vol 7, 2016. Frontiers Media SA, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01280. | |

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | [6] F.G. Schaap, A.E. Kremer, W.H. Lamers, P.L. Jansen, I.C. Gaemers. Fibroblast growth factor 21 is induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress | ||

Biochimie, 95 (2013), pp. 692-699, 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.019 | Biochimie, 95 (2013), pp. 692-699, 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.019 | ||

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [7] Li, Dahui et al. "Genotoxic Evaluation Of The Insecticide Endosulfan Based On The Induced GADD153-GFP Reporter Gene Expression". Environmental Monitoring And Assessment, vol 176, no. 1-4, 2010, pp. 251-258. Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/s10661-010-1580-7. |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [8] Park, Jong Sung et al. "Isolation, Characterization And Chromosomal Localization Of The Human GADD153 Gene". Gene, vol 116, no. 2, 1992, pp. 259-267. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/0378-1119(92)90523-r. |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [9] Mitra, Sumegha et al. "Gadd45a Promoter Regulation By A Functional Genetic Variant Associated With Acute Lung Injury". Plos ONE, vol 9, no. 6, 2014, p. e100169. Public Library Of Science (Plos), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100169. |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [10] Cell line available from ATCC at: https://www.atcc.org/Products/All/CRL-9096.aspx |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [11] Cell line available from ATCC at: https://www.atcc.org/products/all/CRL-2254.aspx |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [12] More detailed information regarding this plasmid is available from Addgene here: https://www.addgene.org/13031/ . pcDNA3-EGFP was a gift from Doug Golenbock (Addgene plasmid # 13031) |

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

| − | [ | + | [13] Plasmid map created with software from SnapGene. Software is available at: snapgene.com |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 392: | Line 429: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<div style='padding-top: 100px;'></div> | <div style='padding-top: 100px;'></div> | ||

Latest revision as of 02:15, 18 October 2018

Bioassay Design

Promoter Constructs

Host Strains

Chemicals of Concern

Plasmid

Measurement

Extensions

Project Design Notebook

References

Project Design

Bioassay Design

We designed a mammalian cell-based bioassay that reports activation of specific stress pathways via fluorescence, for use in environmental toxicology. To do this, we selected transcriptionally regulated target genes which are present in mammalian cells and are involved in stress pathways. We isolated the promoters with transcription factor binding sites from these target genes and coupled them to a fluorescent reporter gene. We selected EGFP, a variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP is ubiquitous in synthetic biology due to its reliability and ease of measurement [1]. EGFP is derived from GFP and has been optimized for use in mammalian systems. When a chemical of concern is screened using our assay, if it triggers a specific stress response, the reporter gene will be expressed, causing the assay to fluoresce. The fluorescence of the assay can be quantitatively measured and analyzed. This assay will provide data on the effect of chemicals of concern on the physiological health of mammalian cells; measurements may be easily taken a range of concentrations, duration of exposure, salinities, pH, temperatures, nutrient availabilities, and other conditions. This also allows for measurement of synergistic or interfering effects due to multiple chemicals of concern present simultaneously.

We selected 8 promoter constructs derived from 5 target genes (see Figure 1 below) and coupled them to EGFP. This promoter and reporter gene construct were inserted into a plasmid and transfected into two cell lines (see Figure 2 below). The resulting bioassays were exposed to different chemicals of concern at a variety of concentrations and conditions (see Figure 3 below).

Why not use whole organisms?

A cell-based approach cannot replace in vivo toxicology studies. However, these studies require extensive funding, time, and other resources. By developing a relatively low-cost, cell-based bioassay, preliminary data may be quickly gathered, allowing for more informed decision making as to which in vivo studies are necessary. By using a cell-based preliminary assay, it is our hope that researchers will be able to quickly gather data, make more informed decisions, and save resources. Our cell-based bioassay may also be used to add to the body of knowledge concerning the effect of specific chemicals of concern on the physiological health of mammalian cells and the mechanism of stress.

Why not use cell-free biochemical assays, such as ELISA?

Antibody-based assays, such as Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), have been very successful in biomedical research, environmental toxicology, and other fields [2]. These cell-free methods involve selective binding of a target molecule to a prepared antibody. Such methods are very successful at identifying single, known compounds in an environmental sample, but do not provide any data regarding the effect of the chemical of concern on the health of a living cell. Similarly, the tools of analytical chemistry and organic chemistry may be used to great success when identifying molecules, but do not provide any data regarding the actual effect on a living cell.

Why use synthetic biology?

The goal of our bioassay is to create a tool that can be used to better understand the effect on the physiological health of mammalian cells of environmental toxins. An alternative way to achieve this knowledge is to expose cells to the chemicals of concern, lyse the cells, isolate the RNA, and run a quantitative-real-time-reverse-transcription-PCR in order to characterize and quantify the mRNAs present in the cell. However, this approach has limitations. It requires lysing the cells and cannot be used to gather real-time data about the behavior of the same cell over time. By using a fluorescent reporter gene, we can measure the induction of the reporter gene over time without lysing cells and can more easily take a large number of data points across different chemicals of concern, concentrations, and other variables. A fluorescent bioassay also reduces the amount of work required to measure many data points, compared to PCR based methods. Our bioassay also makes possible the future study of the behavior of a single cell over time after exposure to a chemical of concern, with the aid of microfluidics.

Why use mammalian cells?

We chose to use mammalian cells because they make much more accurate models for human health than bacteria or yeast. Furthermore, within the iGEM competition and the field of synthetic biology as a whole, there has been relatively little work with mammalian systems, compared to bacteria, yeast, and algae. Working with mammalian cells brings a variety of new challenges and opportunities to iGEM: they are more difficult and expensive to culture than bacteria, they require specialized equipment and safety training, they can be used to produce proteins suitable for use in human therapeutics (due to similar post-translational modifications), and they can be used for more complicated circuits and pathways utilizing spatial/temporal differentiation [3].

Why not use human cells?

Although human cell lines would make a superior model for human disease, compared to cell lines derived from hamsters and mice, for our project we chose not to use human cells. Work involving human cells requires specialized facilities, equipment, resources, and safety training. Human cells require a BSL-2 lab, which would have been more difficult for our team to use than our regular wetlab space, which is BSL-1. Additionally, as our project took place in the context of the iGEM competition, we wanted for other teams to be able to easily reproduce our findings and expand them. By using human cell lines, many teams, which lack access to a BSL-2 lab, would have had more difficulty in expanding upon our project. It would be relatively straightforward to insert our genetic constructs to a human cell line, and this presents an opportunity to extend our project.

Promoter Constructs

Table 1 shows the promoter constructs we used and the target genes from which they were derived. Full FASTA sequences for our promoters are available here.

Table 1. Promoter Constructs

| Construct | Target Gene | Species of Origin | Stress Pathway | Size | Further Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT1 | Metallothionein 1 | Mus musculus | Oxidative, heavy metal | 305 nucleotides | [4] |

| MT2_1 | Metallothionein 2 | Homo sapiens | Oxidative, heavy metal | 377 nucleotides | [5] |

| MT2_2 | Metallothionein 2 | Homo sapiens | Oxidative, heavy metal | 59 nucleotides | [5] |

| MT2_3 | Metallothionein 2 | Homo sapiens | Oxidative, heavy metal | 60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 5’ end | [5] |

| MT2_4 | Metallothionein 2 | Homo sapiens | Oxidative, heavy metal | 60 nucleotides; construct MT2_2 plus one base at 3’ end | [5] |

| FGF | FGF21 | Homo sapiens | Unfolded protein response (UPR), endoplasmic reticulum stress | 695 nucleotides | [6] |

| GD153 | GADD153 | Cricetulus griseus | Organochlorine biocides, genotoxins | 811 nucleotides | [7], [8] |

| GD45 | GADD45α | Homo sapiens | Genotoxins, mechanical stress | 1006 nucleotides | [9] |

Host Strains

Table 2. Host Strains

| Host Strain | Description | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| CHO-DG44 | An immortal, adherent cell line derived from Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus) ovary cells. The strain we used is dihydrofolate reductase deficient. | ATCC: CRL-9096 [10] |

| AML-12 | An immortal, adherent cell line derived from mouse (Mus musculus) liver cells. | ATCC: CRL-2254 [11] |

Chemicals of Concern

Table 3. Chemicals of Concern

| Chemical name | Occupational limit | LD50 | Klamath Environmental concentration | Cytotoxicology (In micromoles per liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide | 75 mg/L | 2000 mg/kg | -- | Relevant dose is 60 uM |

| Warfarin | 0.1 ug/L | 374 mg/kgmice186 mg/kg rats | Qualitatively detected by Tom Young’s lab; unpublished data | Relevant dose is 0.0316 – 31.6 μM |

| 2,4-D | 10 ug/L | 2019 ppm (min)12979 ppm(max) | 0.424 - 7.49 ppm | - |

| Copper sulfate | 1 ppb by inhalation | 30 mg/kg | Copper measured at concentration of 19-67 ppm (112uM - 420uM) | Relevant dose is & lt;1.3ppm (6.25uM) |

| Metam Sodium | Limit of irritation 22 ug/L | 781 mg/kg (rat)1836 ppm (min) | 131309.21 kg | - |

Plasmid

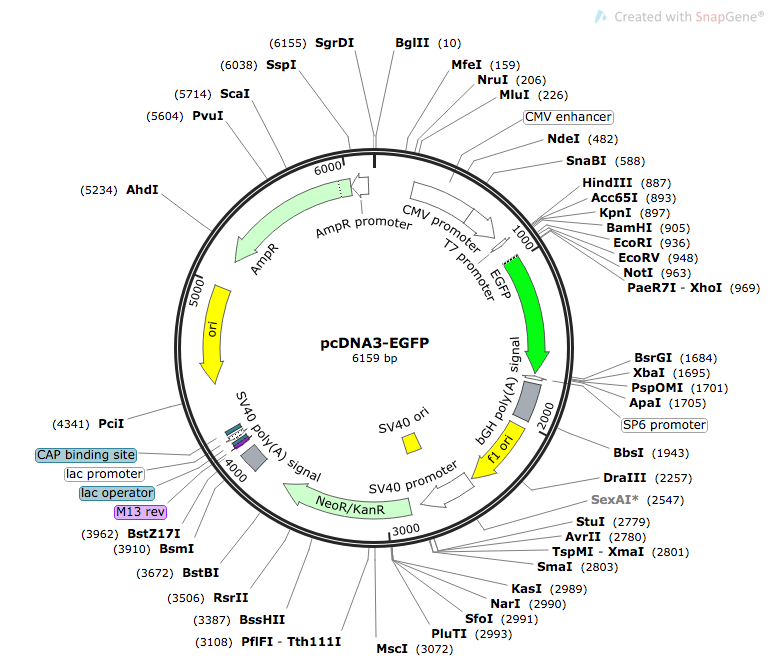

We used pcDNA3-EGFP as our plasmid [12]. The original plasmid is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Map of pcDNA3-EGFP [13]

To prepare our constructs, we used restriction enzymes to remove the CMV enhancer, CMV promoter, and the T7 promoter. Promoter sequences were inserted using either restriction digest or Sequence and Ligation Independent Cloning (SLIC). Figure 2 below shows the complete plasmid for construct MT2_1.

Figure 2. Map of pcDNA-EGFP_MT2_2 [13]

Measurement

Our bioassay was constructed on 96 well plates. Plates were seeded with 30,000 cells/well for AML12 cells and 20,000 cells/well for CHO cells and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. The cells were seeded such that 24 hours after reaching they would be at 70%-90% confluence. At this time, we transfected our cells with the construct containing the target promoter with reporter gene and allowed to sit for another 24 hours. Next, the complete growth media present in the wells were aspirated and replaced with clear media containing chemical of concern. We experimented with use of both a Tecan plate reader and a fluorescent microscope for measurement. For a full report on our measurement practices, please visit our measurement page and our experiments page.

Extensions

Our project opens up new opportunities for work with mammalian cells in the iGEM competition. We have created comprehensive protocols for working with two mammalian cell lines, AML-12, and CHO-DG44, which may be downloaded on our Experiments Page. By adding new mammalian parts to the registry, future teams will have the ability to easily access useful mammalian regulatory elements for use in their own constructs. Future teams may also benefit from our protocol for measuring fluorescence of adherent mammalian cells. One extension of our work is to transfect our construct into human cell lines. By using human cells, the bioassay will be a more accurate model for human health.

Project Design Notebook

Project Design Notebook

References

[1] “PDB101: Molecule of the Month: Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP).” PDB-101, RCSB PDB, June 2003, pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/42.

[2] Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA)/Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Rudolf M. Lequin

Clinical Chemistry Dec 2005, 51 (12) 2415-2418; DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051532

[3]Kis Z, Pereira HSA, Homma T, Pedrigi RM, Krams R. 2015 Mammalian synthetic biology: emerging medical applications. J. R. Soc. Interface 12 : 20141000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.1000

[4] Larochelle, Olivier & Labbé, Simon & Harrisson, Jean-François & Simard, Carl & Tremblay, Véronique & St-Gelais, Geneviève & Govindan, Manjapra Variath & Seguin, Carl. (2008). Nuclear Factor-1 and Metal Transcription Factor-1 Synergistically Activate the Mouse Metallothionein-1 Gene in Response to Metal Ions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 283. 8190-201. 10.1074/jbc.M800640200.

[5] Santos, Anderson K. et al. "Expression System Based on An MtIIa Promoter to Produce Hpsa In Mammalian Cell Cultures". Frontiers in Microbiology, vol 7, 2016. Frontiers Media SA, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01280.

[6] F.G. Schaap, A.E. Kremer, W.H. Lamers, P.L. Jansen, I.C. Gaemers. Fibroblast growth factor 21 is induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress

Biochimie, 95 (2013), pp. 692-699, 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.019

[7] Li, Dahui et al. "Genotoxic Evaluation Of The Insecticide Endosulfan Based On The Induced GADD153-GFP Reporter Gene Expression". Environmental Monitoring And Assessment, vol 176, no. 1-4, 2010, pp. 251-258. Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/s10661-010-1580-7.

[8] Park, Jong Sung et al. "Isolation, Characterization And Chromosomal Localization Of The Human GADD153 Gene". Gene, vol 116, no. 2, 1992, pp. 259-267. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/0378-1119(92)90523-r.

[9] Mitra, Sumegha et al. "Gadd45a Promoter Regulation By A Functional Genetic Variant Associated With Acute Lung Injury". Plos ONE, vol 9, no. 6, 2014, p. e100169. Public Library Of Science (Plos), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100169.

[10] Cell line available from ATCC at: https://www.atcc.org/Products/All/CRL-9096.aspx

[11] Cell line available from ATCC at: https://www.atcc.org/products/all/CRL-2254.aspx

[12] More detailed information regarding this plasmid is available from Addgene here: https://www.addgene.org/13031/ . pcDNA3-EGFP was a gift from Doug Golenbock (Addgene plasmid # 13031)

[13] Plasmid map created with software from SnapGene. Software is available at: snapgene.com

Cenozoic

Cenozoic