| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3f/T--UC_San_Diego--hrp.png" alt="hrp" class="designImg" style="width:60%; margin-left:20%;"/> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/3/3f/T--UC_San_Diego--hrp.png" alt="hrp" class="designImg" style="width:60%; margin-left:20%;"/> | ||

<h5> Figure 6. Visualization of the HRP mechanism </h5> | <h5> Figure 6. Visualization of the HRP mechanism </h5> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>References</h3> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li> Hikoya Hayatsu, Kazuo Negishi, Masahiko Shiraishi, Katsumi Tsuji, Kei Moriyama; Chemistry of Bisulfite Genomic Sequencing; Advances and Issues, Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, Volume 51, Issue 1, 1 November 2007, Pages 47–48 </li> | ||

| + | <li> Genereux, Diane P. et al. “Errors in the Bisulfite Conversion of DNA: Modulating Inappropriate- and Failed-Conversion Frequencies.” Nucleic Acids Research 36.22 (2008): e150. PMC. Web. 18 Oct. 2018. </li> | ||

| + | <li>Brandon W. Heimer, Brooke E. Tam, Hadley D. Sikes; Characterization and directed evolution of a methyl-binding domain protein for high-sensitivity DNA methylation analysis, Protein Engineering, Design and Selection, Volume 28, Issue 12, 1 December 2015, Pages 543–551 </li> | ||

| + | <li> B.W. Heimer, T.A. Shatova, J.K. Lee, K. Kaastrup and H.D. Sikes. “Evaluating the Sensitivity of Hybridization-Based Epigenotyping using a Methyl Binding Domain Protein,” Analyst, 2014, 139 (15): 3695-3701. </li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</body> | </body> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:27, 18 October 2018

Project Design

Overview and Introduction

Liquid biopsy refers to sampling and analysis of non-solid biological tissue, and is used for disease diagnostics and prognosis. In cancer diagnostics and prognostics, liquid biopsy is mainly used to quantify and characterize circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood. ctDNA is short fragment (~180bp) of double stranded DNA derived from tumor cells. When patients develop, ctDNA enriches in blood, containing variable information about cancers such as genetic mutation and methylation.

Liquid biopsy has become an exciting field of biomedical research since it has several advantages compared to common tissue biopsy. As liquid biopsy analyzes blood rather than cancer tissue, it is much less invasive and causes less pain during sample collections. As a result, multiple liquid tests could be carried out in different times to monitor the progress of disease and treatment. Moreover, many cancers have no detectable solid tissues in the early stage, rendering tissue biopsy impossible. By contrast, liquid biopsy could detect a trace of ctDNA released from small amounts of cancer cells even tumor is not present, gaining it huge power for diagnostics.

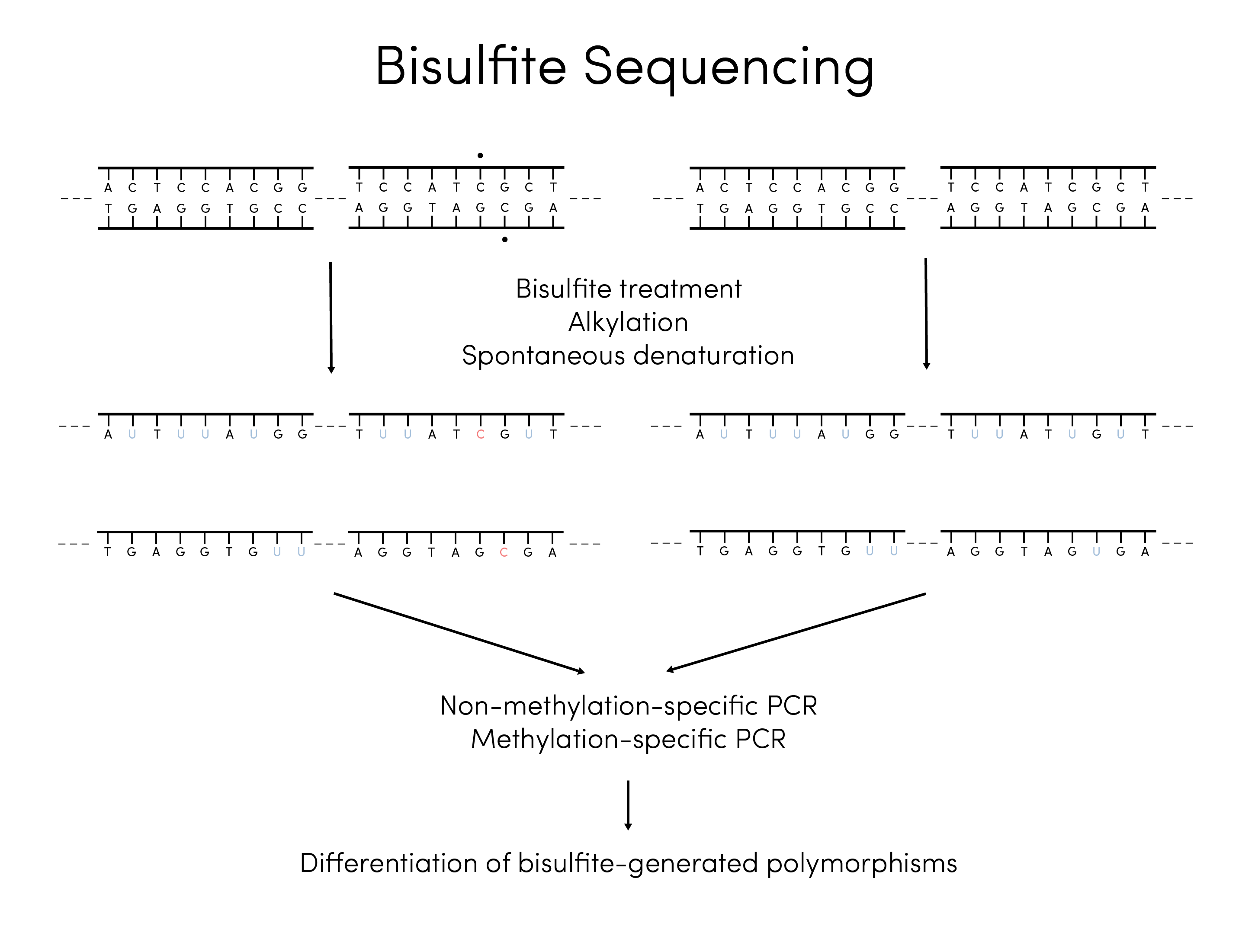

Inspired by this emerging field, our original goal was to develop a general platform that could be used to (1) identify potential diagnostic biomarkers and (2) rapidly detect cancer from a given sample. While doing our literature research and talking to clinical researchers, we came across the idea of using promoter methylation as a quantifiable diagnostic metric. Most analyses of the methylation signal rely on a procedure known as bisulfite sequencing. It begins with converting unmethylated cytosine to uracil with sodium bisulfite, leaving methylated cytosine alone. Converted ctDNA undergoes multiple rounds of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to selectively amplify methylation regions. In the end, amplified product is analyzed, typically by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Although bisulfite sequencing remains the gold standard for ctDNA methylation analysis, we quickly identified several limitations of this method:

Bisulfite treatment causes degradation of most ctDNA and induce incomplete cytosine conversion. Bisulfite treatment typically requires overnight treatment of ctDNA samples.

Multiple rounds of PCR are time-consuming and suffers from amplification bias

.NGS is expensive and not always possible for clinical settings

Figure 1. Overview of bisulfite treatment and sequencing flow

.In addition, the lack of commercially available diagnostic tests is due to the fact that it is quite difficult to determine potential biomarkers; outside of existing literature, there are few resources out there for clinicians and oncologists to rely on when performing a liquid biopsy and choosing a particular gene of interest. Here is just a simple flowchart of all the possible methods that researchers can use in order to gain information about methylation patterns.

Designing our Protein-Based System

To address the first problem that we had identified, our team decided to use synthetic biology coupled with nanomaterials to determine methylation levels of specific sites. A clinically useful assay to profile methylation sites ultimately requires output of a quantitative value. Through literature research, we decided to use beta methylation values which are commonly used In other detection methods such as bisulfite treatment coupled with NGS.

An ideal design should be able to quantitatively measure two values: frequency of total target ctDNA and frequency of methylated target ctDNA. Our design could quantify these two parameters on a single platform by two separate fluorescent readouts.

The central biological part in our design is methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD domain). MBD domain comes from a family of proteins called MBD proteins and retains its functionality when single domain is present. It specifically recognizes symmetrically methylated CpG dinucleotides on double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). On the other hand, MBD domain has much lower affinity toward non-methylated CpG and hemi-methylated CpG. Coupled with signal generation biological parts such as eGFP and Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), MBD domain has the potential to detect and quantify methylation levels of ctDNA.

Current ctDNA methylation methods, such as bisulfite treatment coupled with NGS, are able to quantify methylation levels of specific methylation site. Using MBD domain seems to pose a problem as it is reported to be sequence-independent: MBD domain could not differentiate methylations from different methylation locus. Ambitious to build a simpler, cheaper, and faster device while maintaining its ability to be site specific, we use direct hybridization method based on Yu’s idea.

As Yu et al. reported, target-complementary DNA probes are designed to have single methylation on target locus. When target DNA hybridizes to DNA probe, MBD could differentiate site-specific methylation status by binding to symmetrically methylated duplex but not the hemi-symmetrical ones. However, this MBD method requires modification of target DNA with fluorescent dye, which is difficult when other nonspecific DNA is present in the sample. Moreover, the method failed to quantify the frequency of total target DNA, a crucial parameter for beta value calculation mentioned above. This year, UCSD iGEM team has successfully built upon the MBD method to build a clinically relevant platform for DNA methylation testing.

Figure 2. Preliminary visualization for providing specificity to the MBD protein

Part I. GO Immobilization and Fluorescence Quenching

Cheap and accessible, graphene oxide (GO) has shown many Interesting properties under nanoscale. Previous research has demonstrated that graphene oxide has a strong affinity toward single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and it quenches fluorescent dyes (e.g. FAM) whenever dyes get close to surface.

Inspired by this previous research, we designed multiple DNA probes with a structure shown below. Each DNA probe is attached with a fluorescent dye at 3' end and contains two distinct regions: GO Interacting region and target recognition region. GO Interacting region is designed to contain high GC content which strengthens probe-GO Interaction based on literature. Target recognition region Is complementary to part of target ctDNA; It also contains a 5' methylated cytosine for later detection purpose (see part IV). Before applying ctDNA samples, DNA probes are pre-incubated with GO In solution. Noncovalent interaction between ssDNA and GO bring fluorescent dyes close to GO surface, and therefore effectively quench fluorescent signal.

Figure 3. Sample target probe design

Part II. Hybridization of target ctDNA with probes recovers fluorescence

Figure 4. Using exonuclease to digest DNA probe and amplify signal

A typical silicon gel-purified ctDNA sample contains at least three DNA entities: target DNA with methylation, target DNA without methylation, and nonspecific DNA. Target ctDNA, no matter methylated or not, will specifically hybridize with recognition region of probe DNA to form partial dsDNA duplex. Such duplex significantly weakens DNA-GO interaction and therefore pushes fluorescent dye away from GO surface. This process recovers fluorescent signal, which could be used to quantify target ctDNA concentration. On the other hand, non-specific DNA could not form duplex with DNA probes. GO could absorb this non specific ssDNA to minimize false positive signal.

Part III. Signal amplification via ExoIII digestion of excess DNA probes

Fluorescent dye is sensitive toward DNA detection in general. However, ctDNA exists in a much lower concentration than most biosensor targets. As a result, we employ two enzymatic amplification strategies in our design to improve device sensitivity. The first strategy is exonuclease III (Exo III) digestion. (See Part V for second strategy). E.coli Exo III specifically digest dsDNA duplex from a blunt or recessive 3’ end. ctDNA typically has a length of 180 bp, while DNA probe in our design has a length of ~25bp. As a result, DNA probe will mostly form recessive 3’ end, which is the substrate of exonuclease III. Exo III digests DNA probe and releases single-stranded target DNA and fluorescent dye. Free target DNA could form a duplex with more DNA probes and generate more fluorescent dyes by Exo III. The maximum fluorescent signal could be achieved in 90 min and Exo III could be quenched by 70-degree heating. Impurities such as Exo III can then be washed away prior to performing subsequent steps.

Part IV. MBD fusion proteins recognize symmetrically methylated sites

A. Designing MBD fusion proteins

This summer, we were able to express and purify three different MBD fusion proteins to recognize DNA methylation. The first construct we came out with is mMBD-eGFP, which has been expressed and applied in previous research. In this construct, attached eGFP could give a direct fluorescent readout once MBD bind to methylated CpG and the excess is washed away. Avi tag is a 15 amino acid region specifically recognized by biotin ligase BirA. Once biotin is attached, multiple signal amplification strategies could be used to increase device sensitivity (references, see section B).

Based on this characterized BioBrick, which served as our baseline genetic circuit, we started brainstorming more optimal genetic circuits. Much of our attention has been focused on sensitivity, as the original MBD method was not sensitive enough for ctDNA quantitation. We drew out lessons from a concept called “avidity”. When multiple MBD domains are fused to a single sequence, each domain could interact with methylated CpG. Avidity describes the apparent affinity of such multivalent interaction and it is significantly higher than affinity of single MBD-methylated CpG island. However, increasing numbers of MBD on a single sequence also increases protein size and the possibility of interference between domains. As a result, we chose to fuse two MBD domains with a flexible Gly4Ser2 linker in our improved BioBricks. Combining previous literature and our experimental attempts, we found out although human MBD has higher affinity, mouse MBD is much easier to purified and gives higher yield. As a consequence, we chose to use hybrid human MBD and mouse MBD fusion protein, hoping to maximize protein avidity but in the meantime simplify cloning and protein expression difficulties.

Two improved constructs shown below represent two ways to amplify signal, each with its own merit. Hybrid MBD concatenated with HRP could detect methylated CpG in a single step; it also avoids the need to biotinylate the expressed protein, which is necessary for Hybrid MBD with avi-tag. However, Hybrid MBD with avi-tag is a much smaller protein and therefore less likely to exhibit steric hindrance between domains, which could compromise MBD affinity. As we anticipate MBD-methylated CpG recognition could be applied to scenarios other than ctDNA, we design and validate these different constructs to fulfill different applications.

Figure 5. Overview of MBD-based genetic circuit for promoter methylation detection

B. Discrimination between methylated target and unmethylated sequences

Once the impurities are washed away (see Part III), MBD fusion proteins are applied and incubated. If target CpG is methylated, resulting DNA duplex will form symmetrically methylated CpG as the substrate for MBD domain binding; otherwise resulting DNA duplex is semi-methylated and MBD proteins won’t bind. Excess MBD proteins could be washed away by buffers.

For MBD-eGFP protein, methylated CpG signal could be directly quantified with eGFP fluorescence. Hybrid MBD fused with HRP or avi-tag (with biotin attached) proteins requires the application of substrate and hydrogen peroxide (see part V). Hybrid MBD-avi tag protein needs two extra steps: incubation of commercially available streptavidin-HRP and washing excess streptavidin-HRP.

Part V. HRP amplifies fluorescent signal by enzymatic oxidation of substrate

Our second signal amplification idea comes from the ELISA-type assays. HRP is commonly used to oxidize substrates in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. An oxidized substrate, in this case bi-p,p’-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, gives intense fluorescent signal with excitation at 320nm and emission at 406nm.

Figure 6. Visualization of the HRP mechanism

References

- Hikoya Hayatsu, Kazuo Negishi, Masahiko Shiraishi, Katsumi Tsuji, Kei Moriyama; Chemistry of Bisulfite Genomic Sequencing; Advances and Issues, Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, Volume 51, Issue 1, 1 November 2007, Pages 47–48

- Genereux, Diane P. et al. “Errors in the Bisulfite Conversion of DNA: Modulating Inappropriate- and Failed-Conversion Frequencies.” Nucleic Acids Research 36.22 (2008): e150. PMC. Web. 18 Oct. 2018.

- Brandon W. Heimer, Brooke E. Tam, Hadley D. Sikes; Characterization and directed evolution of a methyl-binding domain protein for high-sensitivity DNA methylation analysis, Protein Engineering, Design and Selection, Volume 28, Issue 12, 1 December 2015, Pages 543–551

- B.W. Heimer, T.A. Shatova, J.K. Lee, K. Kaastrup and H.D. Sikes. “Evaluating the Sensitivity of Hybridization-Based Epigenotyping using a Methyl Binding Domain Protein,” Analyst, 2014, 139 (15): 3695-3701.