Introduction

In biology, timing is very important. The stable recording of cellular events including the timing, location, and concentration of molecules has the potential to advance our understanding of a cell’s history and how cells respond to stimuli. To obtain a molecular record, however, there must be a method to measure and record the dynamics of a specific stimulus.

Recording of environmental and cellular signals has previously been achieved by manipulating transcription and translation in bacteria. However, analyzing information recorded in this manner cannot be passed on to future generations of cells, and the recording process itself is delicate because many extraneous factors contribute to transcription and translation efficiencies. In contrast, recording information directly into the DNA is a permanent change that can be read even after a cells death.

Previously, recombinases and integrases have enabled scientists to record states directly into the genetic code[1]. Despite these advancements, past systems are limited in that they can only take a “snapshot” of the environment, preventing scientists from understanding event order along with the strength and duration of stimuli.

A cellular recording device that can record the timing of stimuli has many potential applications in environmental sensing to detect pH, light, nutrients, pollutants, and more. It can also serve as a useful tool for researchers in determining pathways and uncovering cellular processes. With this goal in mind, we sought out to design a method of true chronological event recording that can achieve temporal resolution of stimuli using recent advancements in CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

CRISPR/Cas9

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) is a prokaryotic immune system that confers resistance to foreign genetic elements such as through from bacteriophages. CRISPR actually refers to the segments of DNA containing short, repetitive base sequences in a palindromic repeat. What most people think of as CRISPR is actually the CRISPR-associated 9 (Cas9) protein. This protein is what scientists have used to revolutionize the field of gene editing.

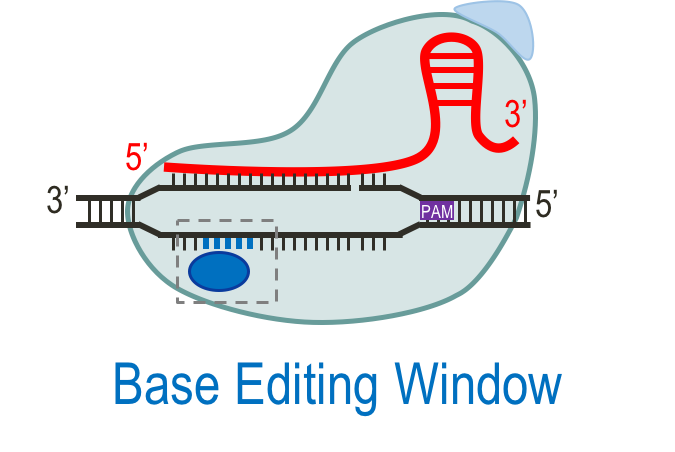

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has two components: a guide RNA (gRNA) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9). The gRNA is a short single-stranded RNA sequence approximately 100 base pairs long. It is composed of two parts the crRNA and the tracrRNA. The tracerRNA is the portion of the sequence that interacts with the CRISPR complex. The crRNA is the 20 nucleotide sequence that gives CRISPR is targeting property by recognizes a specific DNA sequence that matches the crRNA. Directly downstream of the targeted DNA sequence, there is a three-nucleotide sequence called the PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) site that is recognized by Cas9 to allow for proper binding and unwinding of the DNA. Cas9 will search the cellular DNA for PAM sequences. Once found, it will unwind the DNA to determine if the crRNA matches the DNA sequence perfectly. If the sequences match Cas9 will utilize its 2 nuclease domains to makes a double-stranded break in the DNA. After the double-stranded break is created, the cell’s host mechanisms repair the DNA. However, this repair leads to the insertion or deletion of base pairs, resulting in stochastic outcomes.

CRISPR/Cas9 Base Editor

The efficiency and versatility of CRISPR/Cas9 in gene editing has led to the development of promising new tools. Improving upon CRISPR/Cas9’s gene editing abilities, a fusion base editor complex was developed consisting of the DNA base modification enzyme cytidine deaminase (CDA), catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) or Cas9 nickase (nCas9), and a base excision repair inhibitor called uracil glycosylase inhibitor (ugi). This complex can produce a permanent single nucleotide change in the DNA, resulting in a much more certain alteration. The high fidelity allows for researchers to design complex systems while still retaining the targeting specificity of CRISPR/Cas9.

The cytidine deaminase enzyme is able to make a C-G to T-A base pair mutation; after the enzyme binds to a cytidine (C) in the target region of the DNA, it converts the C to a uridine (U). This U-G mismatch is corrected by cellular repair or replication and altered into a T-A base pairing.

In a base editor, a modified version of the Cas9 protein is used. Compared to Cas9, catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) has two silencing mutations (D10A and H841A) that remove endonuclease activity from both of its functional domains. Rather than making a double-stranded cut in the DNA, dCas9 functions more like a shuttle to carry the cytidine deaminase to the targeted DNA sequence. Another modified form of Cas9, called Cas9 nickase (nCas9), has a mutation in only one of the endonuclease domains (D10A). This alteration allows the nCas9 to only cleave one strand of the DNA thereby nicking the non-edited strand, favoring cellular mismatch repair of the nicked strand and leading to more of the desired editing outcome.

Lastly, the component uracil glycosylase inhibitor (ugi) is fused to the base editor fusion complex. This prevents the U-G mismatch created by the cytidine deaminase from changing back to the original C-G instead of the desired T-A mutation[2][3].

In the targeted DNA sequence, maximum base editing occurs when the C or G is located 13-17 base pairs upstream from the PAM site[2].

Base Editing to Record Stimuli

Earlier this year, researchers at Harvard and MIT developed two systems, termed CAMERA and DOMINO respectively, that utilize base editors to record stimuli[4][5]. In their systems, there are two components. A writing module contains the base editor complex and a gRNA driven by a small molecule inducible promoter. The recording component is a plasmid that contains the gRNA recognition sequence of DNA that is to be edited by the writing module.

After chemical inducers are added to the system, a gRNA-base editor complex forms. The gRNA, produced under the presence of the stimulus, guides the base editor to the recording DNA to make the single nucleotide change from a C-G to T-A. Since the recording DNA is contained on a high copy plasmid, these mutations are accumulated linearly over time as more and more recording sequences are modified. Samples of the DNA are taken at various time points in order to determine the amount of editing present at each time point. For readout of the mutation frequency, the researchers for the CAMERA system utilized high-throughput sequencing[4][5].

Amount of editing over time using the CAMERA system with varying concentrations of stimulus (IPTG) [4]

The second system, DOMINO, was able to accomplish temporal logic in which a desired outcome is produced after a certain amount of time has passed. This timing aspect is achieved by designing the recording DNA with a series of overlapping repeats as the target sites for the writing module. The sequence is designed such that the base pair edit on the starting repeat target sequence enables the gRNA to recognize the following repeat in the target sequence, and so on. By converting the upcoming portion of recording DNA to a binding site for the gRNA to recognize and make a new mutation, this process is repeated sequentially. The DOMINO system used Sanger sequencing coupled with an algorithm called Sequalizer (Sequence Equalizer) to determine position-specific mutation frequencies[5].

While both systems are able to record the strength of a stimulus, recording capability is limited to logging an average concentration of stimuli over a period of time. In order to obtain a timeline of events, sampling at multiple time points is required.

CUTSCENE: A Molecular Movie Camera

Our system, termed CUTSCENE, builds upon these foundations by designing a method of true chronological event recording. Rather than just obtaining a snapshot of the average amount of stimuli in a system over time, we wanted to record the dynamics in the system, enabling temporal resolution of stimuli.

CUTSCENE consists of E. coli containing high-copy recording plasmids and a low-copy writing plasmid. A recording plasmid can be thought of like a roll of unexposed film, with each frame being the equivalent to a short, repeating sequence of DNA. The writing plasmid contains our base editor along with two gRNAs. These gRNAs are controlled by separate inducible promoters. The first inducer controls the production of gRNA #1 and sets the cell into recording mode. This sgRNA directs the base editor to move along the DNA repeats, making mutations at a timed rate and constantly shifting which frame is in front of our base editor and available to record. The presence of a stimulus activates the promoter for sgRNA #2. Expression of this sgRNA directs the base editor to mark the current frame with a unique mutation and stops the recording process for that specific plasmid (the other plasmids continue recording). Once the recording process is complete, the DNA film can be developed through the use of Sanger sequencing or restriction enzyme digestion.

This system allows for noninvasive, real-time monitoring of analytes in a system. We use bacteria as our chassis organism, which provides the benefit of functioning in a variety of environments. As this system is limited only by the promoters that can be used to induce the second sgRNA, a variety of signals can be recorded, making the system a universal diagnostic tool. Some useful signals that can be measured include certain cytokines, pH, and pollutants. These could be utilized in diagnosing diseases such as cancers and peptic ulcers. CUTSCENE could be an invaluable tool for researchers as well; by tracking the levels of multiple molecules over the course of a cell’s life, investigators can classify dependent relationships. This information allows biologists to construct vastly improved cellular models, accelerating the rate of scientific discovery.

Read about our system design!

References

[1] Friedland, A. E., Lu, T. K., Wang, X., Shi, D., Church, G., & Collins, J. J. (2009). Synthetic gene networks that count. Science, 324(5931), 1199-1202. doi:10.1126/science.1172005[2] Komor, A. C. Guidelines for base editing in mammalian cells. Retrieved from https://benchling.com/pub/liu-base-editor

[3] Qi, L. S., Larson, M. H., Gilbert, L. A., Doudna, J. A., Weissman, J. S., Arkin, A. P., & Lim, W. A. (2013). Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-Guided Platform for Sequence-Specific

Control of Gene Expression. Cell, 152(5), 1173–1183. doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022

[4] Tang, W. X., & Liu, D. R. (2018). Rewritable multi-event analog recording in bacterial and mammalian cells. Science, 360(6385), 169-+. doi:10.1126/science.aap8992

[5] Farzadfard, F., Gharaei, N., Higashikuni, Y., Jung, G., Cao, J., & Lu, T. K. (2018). Single-Nucleotide-Resolution Computing and Memory in Living Cells. bioRxiv.