Modeling

Overview

In our lab, we aimed to produce Factor 10 activator (a blood clotting agent) and TPA (a de-clotting agent) in E-coli. In response to these goals, we modeled the clot making and clot breaking cascades in order to determine the amount of product (Factor 10 activator or TPA) that is needed to realistically clot or break down blood clots in the most efficient manner. Some questions we used our models to answer were: “How much Factor 10 Activator is needed to add to a wound in order to have the most optimal clotting time?” and “How much TPA is needed in order to break down blood clots faster than current blood thinners?”. In answering these questions, we are able to visualize the implementation of products in their appropriate real life scenarios. In order to create our models, we used Matlab as our program and we modeled enzymatic kinetics using differential equations and Michaelis-Menten, which uses Kcat’s (catalyst rate constants) and Km’s (the concentration for half the maximal reaction rate). The differential equations used show the relationship between physical quantities and their rate of change. Similarly, the Michaelis-Menten equations we wrote relate reaction rate to enzyme [E], to the quantity of product [P] and substrate [S]. To determine the Kcat and Km of the enzymes used in our equations, we referenced published experimental data of reactions and rates, allowing our model to be biologically sound. In addition to this, we used published experimental data in order to validate our results and compare our data to similar experiments conducted in-lab. Specifically delving into our two models, the one for clot making compared the effects of different amounts of Factor 10 activator on the concentrations of fibrin, fibrinogen, thrombin, and prothrombin. From examining experimental data, we were able to find the concentration of Factor 10 needed to achieve a specific concentration of fibrinogen that would enable the increased formation of clots. The model created for clot breaking showed the effect of TPA on plasminogen, plasmin, fibrinogen, fibrin, and fibrin degradation product. In conclusion, our math model allowed us to know how much Factor 10 activator needs to added to a gunshot wound in order to prevent the wound to bleed out, as well as how much TPA would be needed to reduce a blood clot.

Clot Making Result (Left): Clot Activator Decreases Time to Clot by 5 Minutes. Clot Breaking Result (Right): Addition of Exogenous TPA Reduces Clot Breaking Time

What is Mechanistic Modeling?

Let's Begin with a Practical Example

Mechanistic Modeling is the reproduction of the behavior of a system based of the interactions of the system’s natural components.

In order to understand a mechanistic model, consider the following example:

Let’s say that you know that Fred grows 3 fields of wheat, Janet makes 10 cookie mixes, and Baker Bob produces 120 cookies. But as you really like cookies, you try to maximize the amount of cookies you can get from Baker Bob. In order to do so, you decide to make a mechanistic model.

You start off with what you know:

3 Fields of Wheat = 10 cookie mixes = 120 cookies

And then try modifying different parts of the model individually.

On your first attempt, you give Baker Bob a more efficient oven so he can make 130 cookies for every 10 mixes.

Next, you can try giving the cookie mix factory a better assembly line therefore getting 15 cookie mixes and 180 or 195 cookies.

Finally, you try growing genetically modified Wheat and can grow the mass of 6 fields of Wheat on the space of 3, giving you 240 cookies!

What can you learn from this model?

How different parts of your system (fields of wheat, cookie mix, and cookies) relate to each other

How you can increase yield by modifying one or more parts of your system.

As you can see, a simple mechanistic model can allow you to predict the amount of cookies given certain facts, also know as parameters. This example used simple ratios, however for our model, we used differential and Michaelis menten equations.

*mechanistic modeling: Using the laws of physics, mathematics, and in our case, kinetics to predict the end quantities of a substance in a system or see how the different substances in the system relate to each other.

Taking these general principles in mind, we aimed to model the relation of RVV-a and TPA to different substances of interest in the clotting cascade in order to monitor or maximize our desired end result.

What is a Differential Equation?

A differential equation is an equation that relates physical quantities with their rates of change. For us, the rates of change will be the reaction rates of the enzyme [E] in relation to substrate [S], and product [P] concentrations.

What is Michaelis Menten?

The specific type of differential equations we used in our model are called Michaelis Menten equations. Michaelis Menten equations allow us to find the rate of formation of a product given the Vmax (the maximum speed the enzyme can act on the substrate needed to make the product) and the Km (the concentration of substrate where the reaction rate is half of the Vmax). The Km and Vmax are known as the reaction parameters.

Now that we know how objects interact, our next step is to find what interacts. In order to do so, we had to create a schematic of what reactions we wanted to model.

What is our Approach to Modeling?

Overview and Motivation

Our project had two main goals: decrease clotting time to prevent bleedout Increase the degradation time of fibrin (blood clots) in the bloodstream The two substances we wanted to produce through E-Coli were RVV-a, a clotting factor and TPA, which breaks down fibrin. Since these two substances are involved in complex cascading, we wanted to determine the actual effect of these substances on the end result (the presence or absence of clots). In doing so, we would be able to see the effect of our products in real life, allowing us to optimize the design of our project.

Methodology

For both the Making and Breaking, we generated our model using the following steps: 1) Designed model to simulate the concentrations of the following substances over time The input of interest (Bacteriologically synthesized Factor 10 Activator or TPA) Signalling intermediates (e.g. Fibrinogen, Thrombin, etc) The final Product (Fibrin or Fibrin Degradation Products) 2) Assembled parameters and kinetic values from published data. 3) Simulated base cases using normal concentration and kinetic values acquired from prior research. 4) Compared our model predictions with published experimental data. 5) Analysed the model by testing multiple concentrations for the input of interest.

Clot Making Model

Clot Making Schematic

Shows the substrate RVV-X acts on, as well as how it affects other enzymes and products in the clotting cascade. In the absence of RVV-X, Factor VIIa activates Factor X.

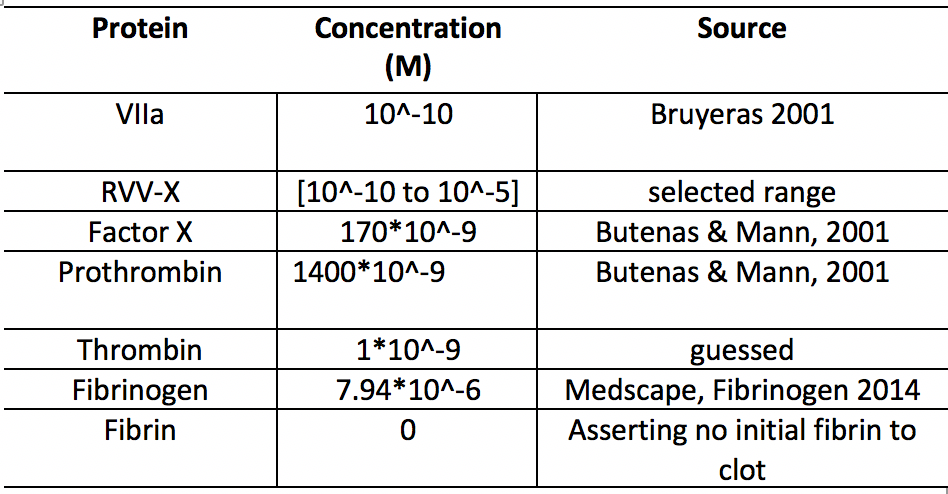

Clot Making Initial Conditions and Parameters

Building the Clot Making Model

We first began by modeling the base case where there is no RVVa in the system, so factor X is activated by VIIa which is endogenously found at low (nM levels in the blood).

Factor VIIa concentration is constant because it is not being used up in the enzymatic reaction to activate Factor X. Target fibrin concentration for healthy clot formation was calculated from Levi, et al. 2015 ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3919717/)

As Factor X decreases, Activated Factor X increases.

As Prothrombin decreases, Thrombin increases.

As Fibrinogen decreases, Fibrin increases.

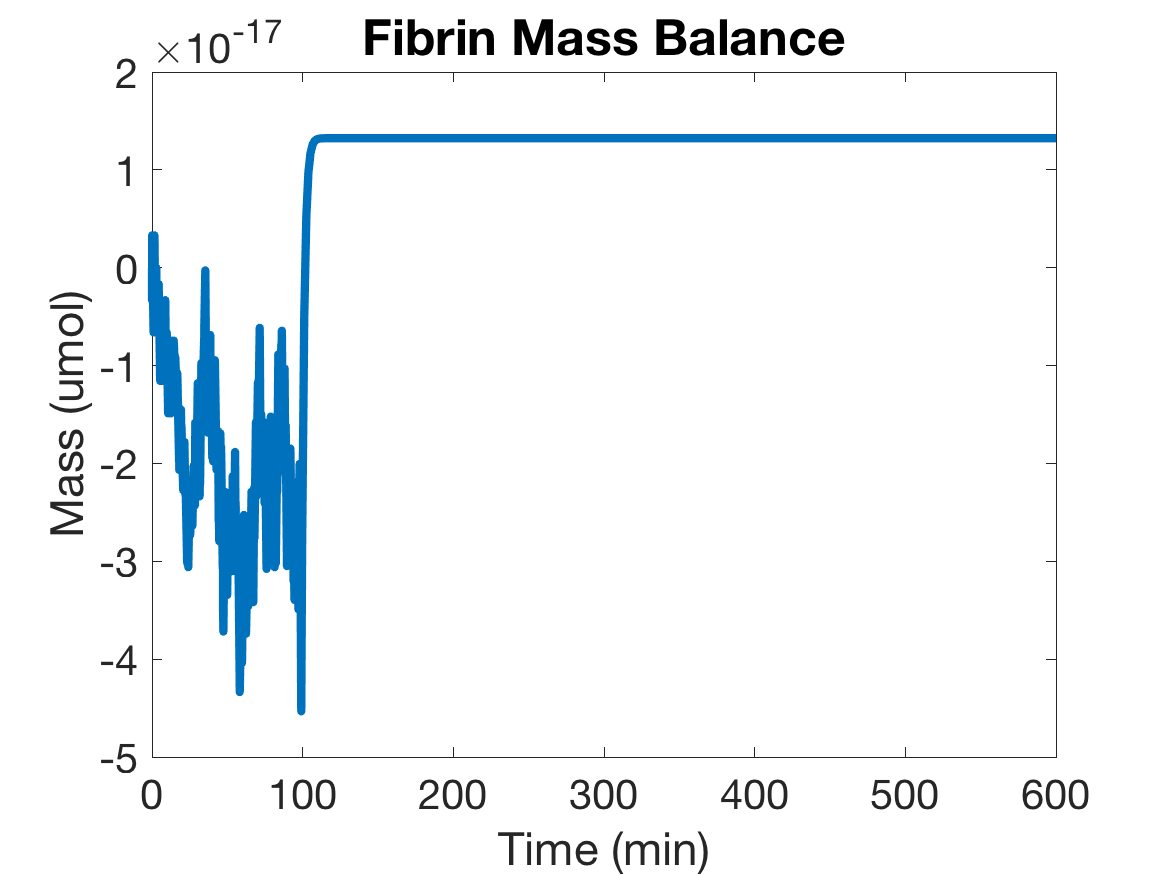

As a way to verify the accuracy of our model’s equations, we modeled the change in mass over time. To do this, we lumped the similar proteins (like thrombin and prothrombin or fibrin and fibrinogen) together. If our model is correct, mass will remain relatively constant throughout the system though it may change between the lumped forms. As shown below, the mass balances of both Thrombin and Fibrin are relatively constant.

Clot Making Results and Conclusions

Introducing RVV-X at time = 0 at various concentrations results in a decrease in time needed to reach target fibrin concentrations of 5 minutes. This change is largely due to the effect RVV-X has on Factor X.

Clot Breaking Model

Clot Breaking Schematic

Shows the substrate TPA acts on and how it affects other substrates to degrade fibrin.

Clot Breaking Initial Conditions and Parameters

Building the Clot Breaking Model

Using concentrations and parameters from experiments with human endogenous tissue-type plasminogen activator, we simulated the concentrations of proteins over time.

Concentration of tissue plasminogen activator over time is constant since it is unused through the enzymatic activation of plasmin.

As Plasminogen concentration decreases, Plasmin concentration increases:

Increases in Plasmin lead to Fibrin degradation on a faster time scale:

To check our model’s equations, we modeled the change in mass over time. In order for mass to be conserved, we would expect for the sum of Plasminogen and Plasmin, as well as the sum of Fibrin and Fibrin Degraded over time to be close to zero, which we observe.

Clot Breaking Results and Conclusions

Increasing the amount of TPA initially in the system, results in a five fold decrease in time for clot degradation:

This result shows that varying a 10 fold increase in TPA concentration could half the fibrinolysis time. In ischemic diseases such as stroke, this time difference could be life saving. A further sensitivity analysis that varies the concentrations of other proteins and kinetic rates needs to be conducted to better understand the factors most important to fibrinolysis time.

Future Work

In the future, we would like to find the optimum quantity of product to put in the system by evaluating the therapeutic range and optimum concentration of our produced enzyme to administer to people. In addition, we would like to see how these concentrations would vary with different modes of administration such as through a gel, bolus dose, or powder on a membrane.

Our modeling project has evolved greatly due to the help of Feilim Mac Gabhann’s lab. After reviewing our initial code, Dr. Mac Gabhann encouraged us to find a target value that we would like to achieve so that we would be able to quantify our achievements.

Citations

Hopfner, Karl-Peter, Katharina Häussermann, Annette Karcher, Erhard Kopetzki, Robert Huber, Richard Alan Engh and Wolfram Bode. “Converting blood coagulation factor IXa into factor Xa: dramatic increase in amidolytic activity identifies important active site determinants.” The EMBO journal 16 22 (1997): 6626-35.

Kalita, Bhargab, Aparup Patra, Shagufta Jahan, and Ashis K. Mukherjee. "First Report of the Characterization of a Snake Venom Apyrase (Ruviapyrase) from Indian Russells Viper (Daboia Russelii) Venom." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 111 (2018): 639-48. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.038.

Mukherjee, Ashis K. “The Pro-Coagulant Fibrinogenolytic Serine Protease Isoenzymes Purified from Daboia Russelii Russelii Venom Coagulate the Blood through Factor V Activation: Role of Glycosylation on Enzymatic Activity.” Ed. Ingo Ahrens. PLoS ONE 9.2 (2014): e86823. PMC. Web. 18 Oct. 2018.

Brown, Mark A., Leisa M. Stenberg, and Johan Stenflo. "Coagulation Factor Xa." Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes, 2013, 2908-915. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-382219-2.00642-6.

Sinniger, Valerie, R. Elizabeth Merton, Pere Fabregas, Jordi Felez, and Colin Longstaff. "Regulation of Tissue Plasminogen Activator Activity by Cells." Journal of Biological Chemistry274, no. 18 (1999): 12414-2422. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.18.12414.

Bannish, Brittany E., Irina N. Chernysh, James P. Keener, Aaron L. Fogelson, and John W. Weisel. "Molecular and Physical Mechanisms of Fibrinolysis and Thrombolysis from Mathematical Modeling and Experiments." Scientific Reports7, no. 1 (2017). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06383-w.

Kim, Dong-Young, Seong H. Cho, Tetsuji Takabayashi, and Robert P. Schleimer. "Chronic Rhinosinusitis and the Coagulation System." Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Research7, no. 5 (2015): 421. doi:10.4168/aair.2015.7.5.421.