Merveisler (Talk | contribs) |

Merveisler (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<h1 style="text-align: center;">MODELING</h1> | <h1 style="text-align: center;">MODELING</h1> | ||

| − | <h2 style="text-align: | + | <h2 style="text-align: center;"><br /><strong>a) </strong>MODELING<strong> FOR EXTERNAL csgA</strong></h2> |

| − | <p style="text-align: | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><br />In the modeling part of our project, the main aim is to determine total number<br />of external csgA proteins which change according to time since one csgA<br />protein can capture one penicillin molecule due to binding stoichiometry. To<br />model this idea, we benefit from TU_Delft 2015 iGEM team equation system.<br />In our system we are using a promoter which can be induced by L –<br />arabinose. This is an iGEM part therefore we are using the data from experience<br />page of part registry (BBa_I0500)(6).</p> |

| − | <p style="text-align: | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/6/6e/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG-- Model1.png" alt="" /><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/3/34/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model2.png" alt="" width="599" height="562" /></p> |

| − | <p style="text-align: | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p>In order to get external csgA amount per cell at a time point, Table 1 should be solved. As seen, there are some variables which should be calculated. b and c sections of modeling are made for these calculations.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">In order to get external csgA amount per cell at a time point, Table 1 should be solved. As seen, there are some variables which should be calculated. b and c sections of modeling are made for these calculations.</p> |

| − | <h2><strong>b) MODELING FOR GROWTH CURVE</strong></h2> | + | <h2 style="text-align: center;"><strong>b) MODELING FOR GROWTH CURVE</strong></h2> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p>For the bacterial growth curve, same equations are used with TU_Delft 2015 iGEM team. The difference of the equations is that our bacteria are growth in minimal media (M63) at 30 °C for 3 days in order to operate curli operon (9). Therefore, different conditions are tried in growth equation.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">For the bacterial growth curve, same equations are used with TU_Delft 2015 iGEM team. The difference of the equations is that our bacteria are growth in minimal media (M63) at 30 °C for 3 days in order to operate curli operon (9). Therefore, different conditions are tried in growth equation.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/c/c7/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model3.png" alt="" width="634" height="331" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/c/c7/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model3.png" alt="" width="634" height="331" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/d/d0/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model4.png" alt="" width="520" height="520" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/d/d0/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model4.png" alt="" width="520" height="520" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/2/2c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model5.png" alt="" width="618" height="405" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/2/2c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model5.png" alt="" width="618" height="405" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/8/8e/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model6.png" alt="" width="615" height="400" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/8/8e/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model6.png" alt="" width="615" height="400" /></p> |

| − | <p>According to graphs, although the conditions are different from normal growth conditions (normal media, 37 °C) the reaching of stationary phase and approximately 0 growth rate occur after 7 hours later. Therefore we assume that our bacteria grow with Table 3 equations.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">According to graphs, although the conditions are different from normal growth conditions (normal media, 37 °C) the reaching of stationary phase and approximately 0 growth rate occur after 7 hours later. Therefore we assume that our bacteria grow with Table 3 equations.</p> |

| − | <h2><strong>c)MODELING FOR PROMETER ACTIVITY</strong></h2> | + | <h2 style="text-align: center;"><strong>c)MODELING FOR PROMETER ACTIVITY</strong></h2> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p>To model promoter activity, we are using the data from iGEM registry page of <u>BBa_I0500.</u></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">To model promoter activity, we are using the data from iGEM registry page of <u>BBa_I0500.</u></p> |

| − | <p>The best way of measuring the arabinose inducted promoter is using the GFP concentration according to time after induction. GFP production can be predicted following equations.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">The best way of measuring the arabinose inducted promoter is using the GFP concentration according to time after induction. GFP production can be predicted following equations.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/4b/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model7.png" alt="" width="619" height="194" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/4b/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model7.png" alt="" width="619" height="194" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/45/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model8.png" alt="" width="624" height="508" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/45/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model8.png" alt="" width="624" height="508" /></p> |

| − | <p>To reach the Prom_act variable, we solve the ordinary differential equations in Table 4 by hand. However, we need the amount of mature GFP protein at a time point.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">To reach the Prom_act variable, we solve the ordinary differential equations in Table 4 by hand. However, we need the amount of mature GFP protein at a time point.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/7/71/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model9.png" alt="" width="620" height="424" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/7/71/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model9.png" alt="" width="620" height="424" /></p> |

| − | <p>10 mM of L-Arabinose refers to 0.15 % g/ml solution. From this data, we observe the Fluorescent/OD600 value approximately 5.7 *10<sup>6</sup>. After dimensional changes(fluorescent/OD600=59.7*mass of GFP(8)), at the t=19800 second(5.5 hours) the amount of mature GFP proteins per cell is become 2.65*10<sup>6</sup> protein/cell . The reason of choosing after 5.5 hours is because not only the data given but also the assuming growth rate as 0.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">10 mM of L-Arabinose refers to 0.15 % g/ml solution. From this data, we observe the Fluorescent/OD600 value approximately 5.7 *10<sup>6</sup>. After dimensional changes(fluorescent/OD600=59.7*mass of GFP(8)), at the t=19800 second(5.5 hours) the amount of mature GFP proteins per cell is become 2.65*10<sup>6</sup> protein/cell . The reason of choosing after 5.5 hours is because not only the data given but also the assuming growth rate as 0.</p> |

| − | <p>Also we observe that our promoter is working as “All or non” response. The following figure (Figure 4) shows that 0.2% L-arabinose and 0.75% L-arabinose give roughly same amount of activity in terms of Miller Unit.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">Also we observe that our promoter is working as “All or non” response. The following figure (Figure 4) shows that 0.2% L-arabinose and 0.75% L-arabinose give roughly same amount of activity in terms of Miller Unit.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/4c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model10.png" alt="" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/4c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model10.png" alt="" /></p> |

| − | <p>After the calculations with MATLAB, the promoter activity equals 0.1299 mRNa/(s*cell*copy number) . We assume that the different growing conditions do not affect the promoter activity.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">After the calculations with MATLAB, the promoter activity equals 0.1299 mRNa/(s*cell*copy number) . We assume that the different growing conditions do not affect the promoter activity.</p> |

| − | <h2><strong>RESULTS</strong></h2> | + | <h2 style="text-align: center;"><strong>RESULTS</strong></h2> |

| − | <p>Eventually, the all variables which are absent in Table 2 are calculated. To obtain K<sub>tr.csgA, </sub>proportion calculation is used.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">Eventually, the all variables which are absent in Table 2 are calculated. To obtain K<sub>tr.csgA, </sub>proportion calculation is used.</p> |

| − | <p>(Translated GFP length = 238, Our csgA length 173 à 0.4*238/173=0.55).</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">(Translated GFP length = 238, Our csgA length 173 à 0.4*238/173=0.55).</p> |

| − | <p>In order to get K<sub>t</sub> , we use the steady state conditions of M<sub>csgA.In,</sub> P<sub>csgA.In </sub>and Y(t) since at the steady state, accumulation of internal csgA becomes 0. Therefore,</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">In order to get K<sub>t</sub> , we use the steady state conditions of M<sub>csgA.In,</sub> P<sub>csgA.In </sub>and Y(t) since at the steady state, accumulation of internal csgA becomes 0. Therefore,</p> |

| − | <p>K<sub>tr.csgA</sub>* M<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – b<sub>d</sub>* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – y(t)* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – K<sub>t</sub>* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t)=0</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">K<sub>tr.csgA</sub>* M<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – b<sub>d</sub>* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – y(t)* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t) – K<sub>t</sub>* P<sub>csgA.In</sub>(t)=0</p> |

| − | <p>P<sub>csgA.In</sub>=8.01*10<sup>-5</sup> protein/cell, y=0, M<sub>csgA.In</sub>=1082.5 mRNA/cell</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">P<sub>csgA.In</sub>=8.01*10<sup>-5</sup> protein/cell, y=0, M<sub>csgA.In</sub>=1082.5 mRNA/cell</p> |

| − | <p>Then,</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">Then,</p> |

| − | <p>K<sub>t</sub>=0.0476 1/s</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">K<sub>t</sub>=0.0476 1/s</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/a/ab/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model11.png" alt="" width="607" height="528" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/a/ab/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model11.png" alt="" width="607" height="528" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/3/30/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model12.png" alt="" width="608" height="502" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/3/30/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model12.png" alt="" width="608" height="502" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/b/bc/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model13.png" alt="" width="620" height="472" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/b/bc/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model13.png" alt="" width="620" height="472" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/a/a7/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model14.png" alt="" width="622" height="440" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/a/a7/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model14.png" alt="" width="622" height="440" /></p> |

| − | <p>These results show that after steady state, the amount of protein is not changed by lag phase parameter q<sub>0</sub> (It is kind of measure of capability of fitting the environment). Therefore, our assumption about promoter effectivity and growth rate as taking them same with normal growth conditions. We are using the csgA proteins to capture penicillin after at least 3 days. Moreover, our protein amount is independent from inducer concentration in range of 0.2% and 0.75% . </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">These results show that after steady state, the amount of protein is not changed by lag phase parameter q<sub>0</sub> (It is kind of measure of capability of fitting the environment). Therefore, our assumption about promoter effectivity and growth rate as taking them same with normal growth conditions. We are using the csgA proteins to capture penicillin after at least 3 days. Moreover, our protein amount is independent from inducer concentration in range of 0.2% and 0.75% . </p> |

| − | <p>If graphs would be investigated, we can directly see that after 20 hours, the relation between amount of external csgA with time is linear. To calculate expected external csgA, accordingly captured penicillin amount in terms of molecules, following equation can be used to determine how much time bacteria are incubated.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">If graphs would be investigated, we can directly see that after 20 hours, the relation between amount of external csgA with time is linear. To calculate expected external csgA, accordingly captured penicillin amount in terms of molecules, following equation can be used to determine how much time bacteria are incubated.</p> |

| − | <p>T<sub>exp</sub>= (Penicillin_captured+0.0047)/(1.3731*10<sup>8</sup>)</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">T<sub>exp</sub>= (Penicillin_captured+0.0047)/(1.3731*10<sup>8</sup>)</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/1/1e/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model15.png" alt="" width="557" height="503" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/1/1e/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model15.png" alt="" width="557" height="503" /></p> |

| − | <p>For example to capture approximately 130 μmol of penicillin, the total incubation time of bacteria should be 72 hours (3 days).</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">For example to capture approximately 130 μmol of penicillin, the total incubation time of bacteria should be 72 hours (3 days).</p> |

| − | <p>All graphs except Figure 3 and 4 are drawn by MATLAB. <u>Here</u> is our MATLAB files.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">All graphs except Figure 3 and 4 are drawn by MATLAB. <u>Here</u> is our MATLAB files.</p> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p><strong>Protein 3D Modelling</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>Protein 3D Modelling</strong></p> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p>In our project, we have 2 different conjugated proteins: csgA-pbp1b and BFR-sfGFP. In order to make predictions how they work, we use I-Tasser website. Followings are our proteins 3D structures predicted.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">In our project, we have 2 different conjugated proteins: csgA-pbp1b and BFR-sfGFP. In order to make predictions how they work, we use I-Tasser website. Followings are our proteins 3D structures predicted.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/43/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model16.png" alt="" width="526" height="272" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/4/43/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model16.png" alt="" width="526" height="272" /></p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/3/3c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model17.png" alt="" width="457" height="417" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/3/3c/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model17.png" alt="" width="457" height="417" /></p> |

| − | <p>To create Figure 9, after creating 3D structure by I-Tasser, SwissDock is used to determine binding habits with our ligand, penicillin. As seen, top 10 binding energies show that penicillin molecules tends to bind pbp1b part of csgA-pbp1b. Others are non-specific and can be neglected. Therefore we may conclude that our protein is successful at capturing penicillin.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">To create Figure 9, after creating 3D structure by I-Tasser, SwissDock is used to determine binding habits with our ligand, penicillin. As seen, top 10 binding energies show that penicillin molecules tends to bind pbp1b part of csgA-pbp1b. Others are non-specific and can be neglected. Therefore we may conclude that our protein is successful at capturing penicillin.</p> |

| − | <p>In Figure 10, 3D structure of BFR-sfGFP is shown as green. Blue part of the figure indicates the natural sfGFP. SfGFP part of our protein is overlapped with natural sfGFP. This situation can be concluded as conjugation is made appropriately and sfGFP signal is observed to track our bacteria which produce BFR.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">In Figure 10, 3D structure of BFR-sfGFP is shown as green. Blue part of the figure indicates the natural sfGFP. SfGFP part of our protein is overlapped with natural sfGFP. This situation can be concluded as conjugation is made appropriately and sfGFP signal is observed to track our bacteria which produce BFR.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/c/ce/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model18.png" alt="" width="563" height="446" /></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/parts/c/ce/T--Bilkent-UNAMBG--Model18.png" alt="" width="563" height="446" /></p> |

| − | <p>Figure 11 shows that our BFR-sfGFP protein is working correctly in terms of fluorescent emitting.</p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;">Figure 11 shows that our BFR-sfGFP protein is working correctly in terms of fluorescent emitting.</p> |

| − | <p> </p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"> </p> |

| − | <p><strong>REFERENCES</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>REFERENCES</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong>1-“Automated Live Cell Imaging of Green Fluorescent Protein Degradation in Individual Fibroblasts”, Michael Halter, Alex Tona, Kiran Bhadriraju, Anne L. Plant, John T. Elliott, Cytometry Part A ,71A: 827-834, (2007)</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>1-“Automated Live Cell Imaging of Green Fluorescent Protein Degradation in Individual Fibroblasts”, Michael Halter, Alex Tona, Kiran Bhadriraju, Anne L. Plant, John T. Elliott, Cytometry Part A ,71A: 827-834, (2007)</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong>2-https://greenfluorescentblog.wordpress.com/tag/gfpmut3/, (2012)</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>2-https://greenfluorescentblog.wordpress.com/tag/gfpmut3/, (2012)</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong>3-“Measuring the activity of BioBrick promoters using an in vivo reference standard”, Jason R Kelly, Adam J Rubin, Joseph H Davis, Caroline M Ajo-Franklin, John Cumbers, Michael J Czar, Kim de Mora, Aaron L Glieberman, Dileep D Monie and Drew Endy, Journal of Biological Engineering 2009, 3:4</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>3-“Measuring the activity of BioBrick promoters using an in vivo reference standard”, Jason R Kelly, Adam J Rubin, Joseph H Davis, Caroline M Ajo-Franklin, John Cumbers, Michael J Czar, Kim de Mora, Aaron L Glieberman, Dileep D Monie and Drew Endy, Journal of Biological Engineering 2009, 3:4</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong>4-“Alternative Approach To Modeling Bacterial Lag Time, Using Logistic Regression as a Function of Time, Temperature, pH, and Sodium Chloride Concentration”, Shige Koseki and Junko Nonaka, FEMS Yeast Res 14 (2014) 586–600</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>4-“Alternative Approach To Modeling Bacterial Lag Time, Using Logistic Regression as a Function of Time, Temperature, pH, and Sodium Chloride Concentration”, Shige Koseki and Junko Nonaka, FEMS Yeast Res 14 (2014) 586–600</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong>5- http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB3K3</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong>5- http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB3K3</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 6-http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I0500:Experience</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 6-http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I0500:Experience</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 7- http://www.expressys.com/main_vectors</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 7- http://www.expressys.com/main_vectors</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 8- https://2015.igem.org/Team:TU_Delft/Modeling</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 8- https://2015.igem.org/Team:TU_Delft/Modeling</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 9- “Curli Biogenesis and Function”, Michelle M Barnhart and Matthew R Chapman, Annual Review of Microbiology, 60, 131–147, (2006)</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 9- “Curli Biogenesis and Function”, Michelle M Barnhart and Matthew R Chapman, Annual Review of Microbiology, 60, 131–147, (2006)</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 10-https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 10-https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/</strong></p> |

| − | <p><strong> 11-http://www.swissdock.ch/</strong></p> | + | <p style="text-align: center;"><strong> 11-http://www.swissdock.ch/</strong></p> |

</html> | </html> | ||

Revision as of 02:29, 18 October 2018

MODELING

a) MODELING FOR EXTERNAL csgA

In the modeling part of our project, the main aim is to determine total number

of external csgA proteins which change according to time since one csgA

protein can capture one penicillin molecule due to binding stoichiometry. To

model this idea, we benefit from TU_Delft 2015 iGEM team equation system.

In our system we are using a promoter which can be induced by L –

arabinose. This is an iGEM part therefore we are using the data from experience

page of part registry (BBa_I0500)(6).

In order to get external csgA amount per cell at a time point, Table 1 should be solved. As seen, there are some variables which should be calculated. b and c sections of modeling are made for these calculations.

b) MODELING FOR GROWTH CURVE

For the bacterial growth curve, same equations are used with TU_Delft 2015 iGEM team. The difference of the equations is that our bacteria are growth in minimal media (M63) at 30 °C for 3 days in order to operate curli operon (9). Therefore, different conditions are tried in growth equation.

According to graphs, although the conditions are different from normal growth conditions (normal media, 37 °C) the reaching of stationary phase and approximately 0 growth rate occur after 7 hours later. Therefore we assume that our bacteria grow with Table 3 equations.

c)MODELING FOR PROMETER ACTIVITY

To model promoter activity, we are using the data from iGEM registry page of BBa_I0500.

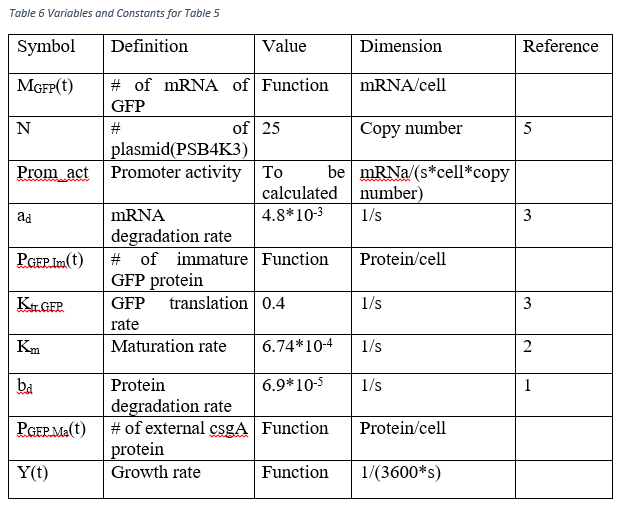

The best way of measuring the arabinose inducted promoter is using the GFP concentration according to time after induction. GFP production can be predicted following equations.

To reach the Prom_act variable, we solve the ordinary differential equations in Table 4 by hand. However, we need the amount of mature GFP protein at a time point.

10 mM of L-Arabinose refers to 0.15 % g/ml solution. From this data, we observe the Fluorescent/OD600 value approximately 5.7 *106. After dimensional changes(fluorescent/OD600=59.7*mass of GFP(8)), at the t=19800 second(5.5 hours) the amount of mature GFP proteins per cell is become 2.65*106 protein/cell . The reason of choosing after 5.5 hours is because not only the data given but also the assuming growth rate as 0.

Also we observe that our promoter is working as “All or non” response. The following figure (Figure 4) shows that 0.2% L-arabinose and 0.75% L-arabinose give roughly same amount of activity in terms of Miller Unit.

After the calculations with MATLAB, the promoter activity equals 0.1299 mRNa/(s*cell*copy number) . We assume that the different growing conditions do not affect the promoter activity.

RESULTS

Eventually, the all variables which are absent in Table 2 are calculated. To obtain Ktr.csgA, proportion calculation is used.

(Translated GFP length = 238, Our csgA length 173 à 0.4*238/173=0.55).

In order to get Kt , we use the steady state conditions of McsgA.In, PcsgA.In and Y(t) since at the steady state, accumulation of internal csgA becomes 0. Therefore,

Ktr.csgA* McsgA.In(t) – bd* PcsgA.In(t) – y(t)* PcsgA.In(t) – Kt* PcsgA.In(t)=0

PcsgA.In=8.01*10-5 protein/cell, y=0, McsgA.In=1082.5 mRNA/cell

Then,

Kt=0.0476 1/s

These results show that after steady state, the amount of protein is not changed by lag phase parameter q0 (It is kind of measure of capability of fitting the environment). Therefore, our assumption about promoter effectivity and growth rate as taking them same with normal growth conditions. We are using the csgA proteins to capture penicillin after at least 3 days. Moreover, our protein amount is independent from inducer concentration in range of 0.2% and 0.75% .

If graphs would be investigated, we can directly see that after 20 hours, the relation between amount of external csgA with time is linear. To calculate expected external csgA, accordingly captured penicillin amount in terms of molecules, following equation can be used to determine how much time bacteria are incubated.

Texp= (Penicillin_captured+0.0047)/(1.3731*108)

For example to capture approximately 130 μmol of penicillin, the total incubation time of bacteria should be 72 hours (3 days).

All graphs except Figure 3 and 4 are drawn by MATLAB. Here is our MATLAB files.

Protein 3D Modelling

In our project, we have 2 different conjugated proteins: csgA-pbp1b and BFR-sfGFP. In order to make predictions how they work, we use I-Tasser website. Followings are our proteins 3D structures predicted.

To create Figure 9, after creating 3D structure by I-Tasser, SwissDock is used to determine binding habits with our ligand, penicillin. As seen, top 10 binding energies show that penicillin molecules tends to bind pbp1b part of csgA-pbp1b. Others are non-specific and can be neglected. Therefore we may conclude that our protein is successful at capturing penicillin.

In Figure 10, 3D structure of BFR-sfGFP is shown as green. Blue part of the figure indicates the natural sfGFP. SfGFP part of our protein is overlapped with natural sfGFP. This situation can be concluded as conjugation is made appropriately and sfGFP signal is observed to track our bacteria which produce BFR.

Figure 11 shows that our BFR-sfGFP protein is working correctly in terms of fluorescent emitting.

REFERENCES

1-“Automated Live Cell Imaging of Green Fluorescent Protein Degradation in Individual Fibroblasts”, Michael Halter, Alex Tona, Kiran Bhadriraju, Anne L. Plant, John T. Elliott, Cytometry Part A ,71A: 827-834, (2007)

2-https://greenfluorescentblog.wordpress.com/tag/gfpmut3/, (2012)

3-“Measuring the activity of BioBrick promoters using an in vivo reference standard”, Jason R Kelly, Adam J Rubin, Joseph H Davis, Caroline M Ajo-Franklin, John Cumbers, Michael J Czar, Kim de Mora, Aaron L Glieberman, Dileep D Monie and Drew Endy, Journal of Biological Engineering 2009, 3:4

4-“Alternative Approach To Modeling Bacterial Lag Time, Using Logistic Regression as a Function of Time, Temperature, pH, and Sodium Chloride Concentration”, Shige Koseki and Junko Nonaka, FEMS Yeast Res 14 (2014) 586–600

5- http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB3K3

6-http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I0500:Experience

7- http://www.expressys.com/main_vectors

8- https://2015.igem.org/Team:TU_Delft/Modeling

9- “Curli Biogenesis and Function”, Michelle M Barnhart and Matthew R Chapman, Annual Review of Microbiology, 60, 131–147, (2006)

10-https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/

11-http://www.swissdock.ch/