Project

Description

The ability to probe the chemical nature of the environment is essential for many basic biological functions, as well as applications that range from security and threat detection to industry, agriculture, and medicine [1-5]. In animals, chemosensory detection is mediated by olfaction (smell) and gustation (taste). Both systems provide essential chemosensory information, but the olfactory system probes chemical space with much higher specificity and selectivity than the gustatory system. Human olfaction prowess is substantial, but other animals, such as dogs, have superior olfaction capabilities and they are often used for chemosensory applications. Despite their superior capabilities, however, animals have several important limitations that restrict their ability and/or effectiveness to serve as surrogate chemosensors [6-8]. There is a clear need to develop artificial chemosensory devices that can provide rapid, sensitive, and selective monitoring, like natural olfactory systems, but that can also provide continuous, reliable, and standardizable function.

Most previously reported artificial chemosensory technologies have used either all artificial components or have integrated only molecular components of olfactory systems into the sensor design [9]. Sensors constructed entirely with artificial components have achieved variable levels of success, but generally lack the sensitivity and ability to detect a wide range of chemical space with the same detail as found in natural olfactory systems. Sensors incorporating molecular components of olfactory systems (eg: olfactory receptor proteins, which are responsible for binding and detecting target chemical species) can be sensitive and have the capability to co-opt expansive detection ability of natural olfactory systems, but they are limited by the fragility of the biological molecular components.

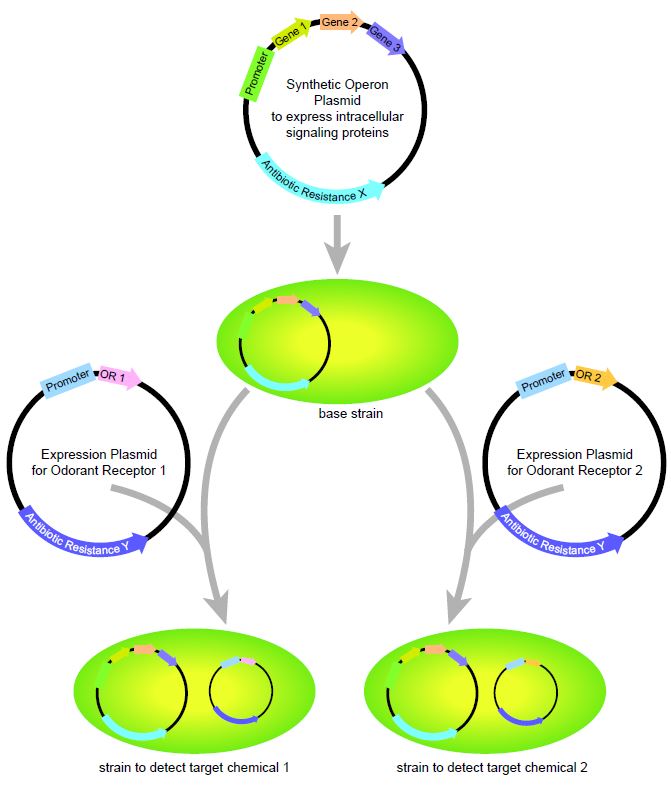

The objective of this project is to produce a cell-based artificial chemosensory detection system. Bacteria are used because of the ease with which they can be genetically manipulated and their ability to be cultured under a wide range of conditions. A limitation, however, is that bacteria do not contain compatible intracellular signaling pathway proteins that can transduce target chemical detection as is found in animal cells. We propose to overcome this challenge by developing a two-plasmid system in which one plasmid contains a synthetic operon encoding the intracellular signaling pathway proteins necessary to effectively transduce target chemical detection by odorant receptor proteins expressed by a separate plasmid. Operons are a group of adjacent genes that are transcribed as a single transcript. This genetic architecture will enable us to express the set of intracellular proteins from a single promoter element. This synthetic operon can be used to generate a host bacterial strain in which an additional plasmid for the expression of an odorant receptor protein can be paired so that different strains can be engineered in order to detect different target chemicals (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Why eNOSE?

The initial goal of USMA West Point’s “eNOSE” project was to develop novel technology in order to enhance warfighter security, particularly threats posed by explosives and chemical weapons. Current detection methods, including canines and ground penetrating radar, have achieved reasonable successes, but they also have significant limitations. Our goal is to harness the sensitivity and power of naturally chemosensory detection that has evolved in animal olfactory systems in order to complement and extended the effectiveness of current detection methods. Chemosensors, such as our “eNOSE” technologies, have a myriad of uses outside of security applications. In healthcare, they can screen patients for pathological conditions by detecting volatile organic chemicals characteristic of specific illnesses. Within industry, this technology can monitor workplace chemical environments in order to alert worked when dangerous conditions are present. Within the food service industry, this technology can be used to screen the quality of ingredients as well as goods intended for consumption. This multitude of uses for chemosensory devices beyond security applications underscores the importance of developing chemosensory technologies, like “eNOSE.”

References

- Giannoukos, S., Brkic, B., Taylor, S., Marshall, A., and Verbeck, G.F. (2016). Chemical Sniffing Instrumentation for Security Applications. Chem Rev 116, 8146-8172.

- Wilson, A.D. (2013). Diverse applications of electronic-nose technologies in agriculture and forestry. Sensors (Basel) 13, 2295-2348.

- Dung, T.T., Oh, Y., Choi, S.J., Kim, I.D., Oh, M.K., and Kim, M. (2018). Applications and Advances in Bioelectronic Noses for Odour Sensing. Sensors (Basel) 18.

- Ko, H.J., Lim, J.H., Oh, E.H., and Park, T.H. (2014). Applications and Perspectives of Bioelectronic Nose. In Bioelectronic Nose, T.H. Park, ed. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), pp. 263-283.

- Gui, Q., Lawson, T., Shan, S., Yan, L., and Liu, Y. (2017). The Application of Whole Cell-Based Biosensors for Use in Environmental Analysis and in Medical Diagnostics. Sensors (Basel) 17.

- Gao, K., Li, S., Zhuang, L., Qin, Z., Zhang, B., Huang, L., and Wang, P. (2018). In vivo bioelectronic nose using transgenic mice for specific odor detection. Biosens Bioelectron 102, 150-156.

- Oh, Y., Lee, Y., Heath, J., and Kim, M. (2015). Applications of Animal Biosensors: A Review. IEEE Sensors Journal 15, 637-645.

- Zhuang, L., Guo, T., Cao, D., Ling, L., Su, K., Hu, N., and Wang, P. (2015). Detection and classification of natural odors with an in vivo bioelectronic nose. Biosens Bioelectron 67, 694-699.

- Cave, J.W., Wickiser, J.K., and Mitropoulos, A.N. (2018). Progress in the development of olfactory-based bioelectronic chemosensors. Biosens Bioelectron.