Contents

Glycolic Acid Production in E. coli

Abstract

Our aim was to produce glycolic acid for the production of biodegradable polymers. Hence, we overexpressed the genes aceA (isocitrate lyase) and ycdW (glyoxylate reductase) in Escherichia coli (E. coli) to synthesize glycolic acid from the glyoxylate cycle intermediate isocitrate. In the end, we successfully characterized our enzymes and verified the production of glycolic acid through both, NADPH and phenylhydrazine-dependent assays, as well as HPLC analysis. We therefore created a pair of BioBricks allowing the community to produce glycolic acid, and submitted them to the iGEM Registry (BBa_K2770003 & BBa_K2770002).

Introduction

Escherichia coli is the most frequently used and a well-established host organism for biotechnological applications. Especially its stable expression system of heterologous genes, fast growth rates and its overall well characterized metabolome and proteome make it a currently indispensable organism in biotechnology.

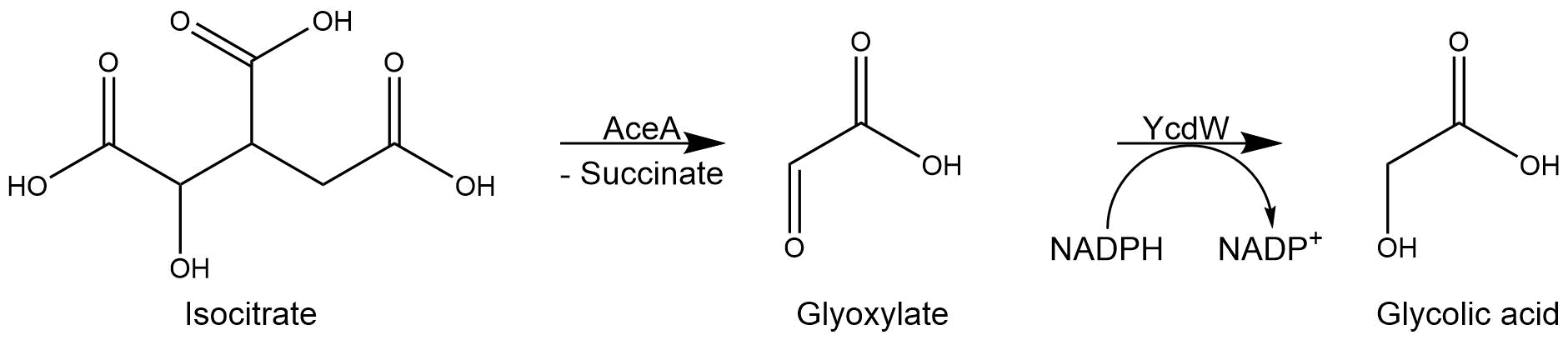

In our project, we modified the glyoxylate cycle of E. coli to produce glycolic acid. For this purpose, we overexpressed two native E. coli genes encoding the isocitrate lyase AceA and the glyoxylate reductase YcdW.

The isocitrate lyase catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate into glyoxylate and succinate. AceA has a tetrameric structure with a molecular mass of 47.5 kDa per subunit. [1]

Figure 1: Tetrameric structure of the isocitrate lyase (AceA) with a molecular mass of 47.5 kDa per subunit.

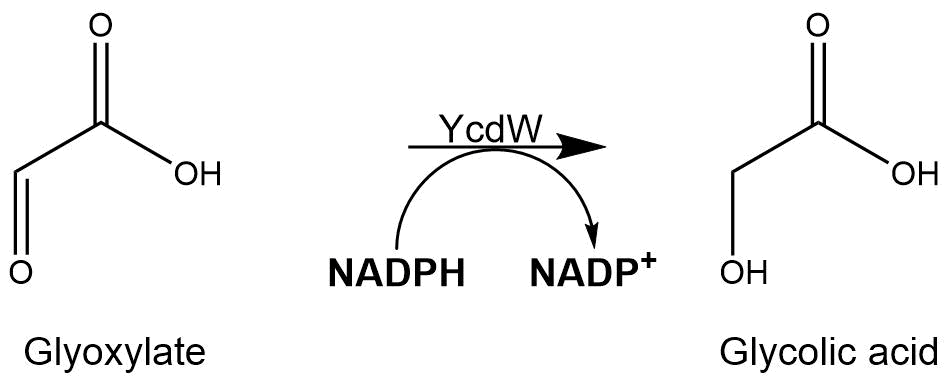

Subsequently, the glyoxylate produced by the isocitrate lyase AceA is further converted into glycolic acid by the NADPH-dependent glyoxylate reductase YcdW. It has a molecular weight of 35.3 kDa[2].

Figure 2: Structure of the NADPH-dependent glyoxylate reductase (YcdW) with a molecular mass of 35.3 kDa.

Through production of both key enzymes, we achieved the synthesis of glycolic acid in E. coli. We assess our accomplishment as a crucial step towards a more environment-friendly production of biodegradable polymers.

Figure 3: Reaction sequence of AceA and YcdW.

Methods

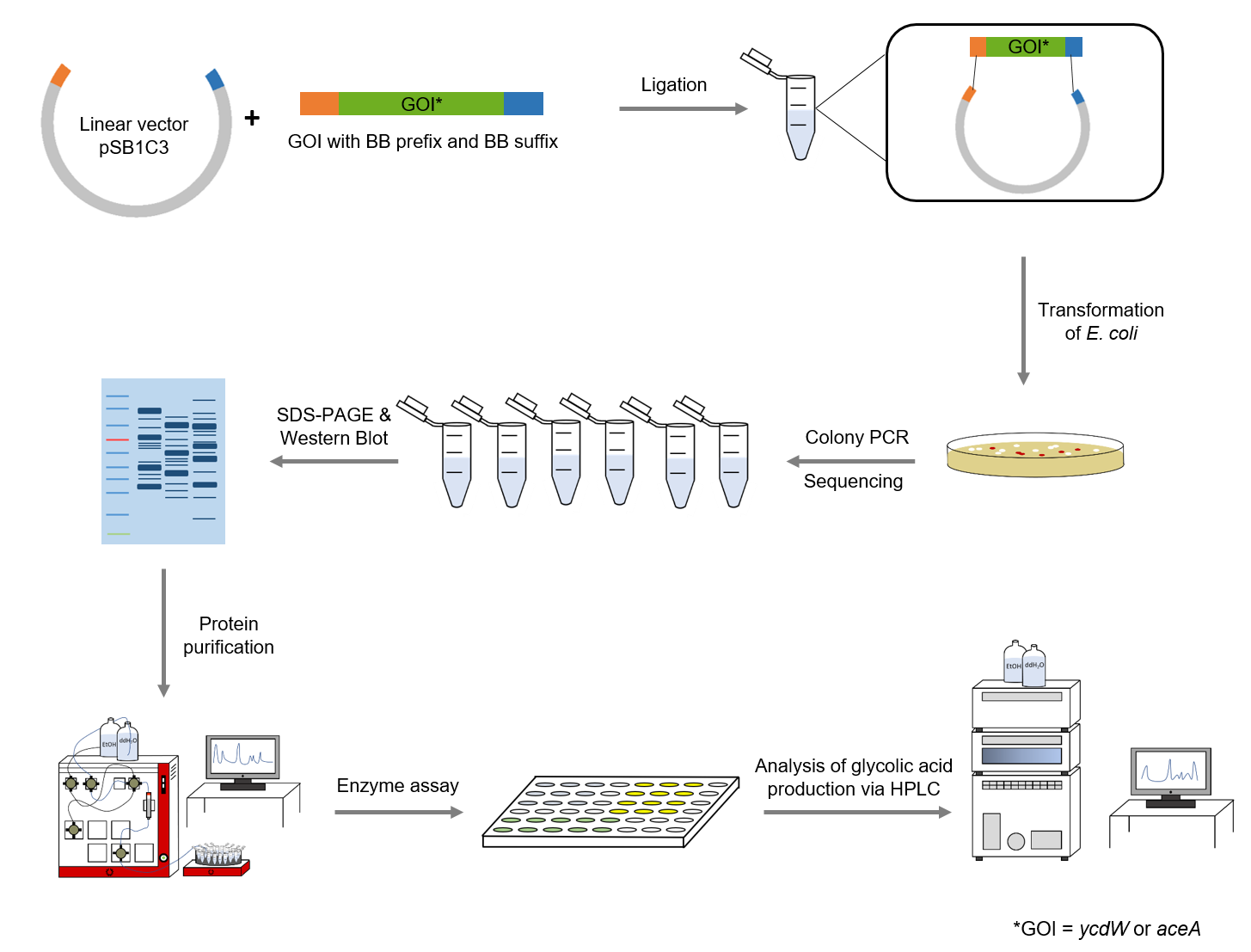

The following methods have been applied in our lab work:

Figure 4: Schematic representation of work flow.

Cloning

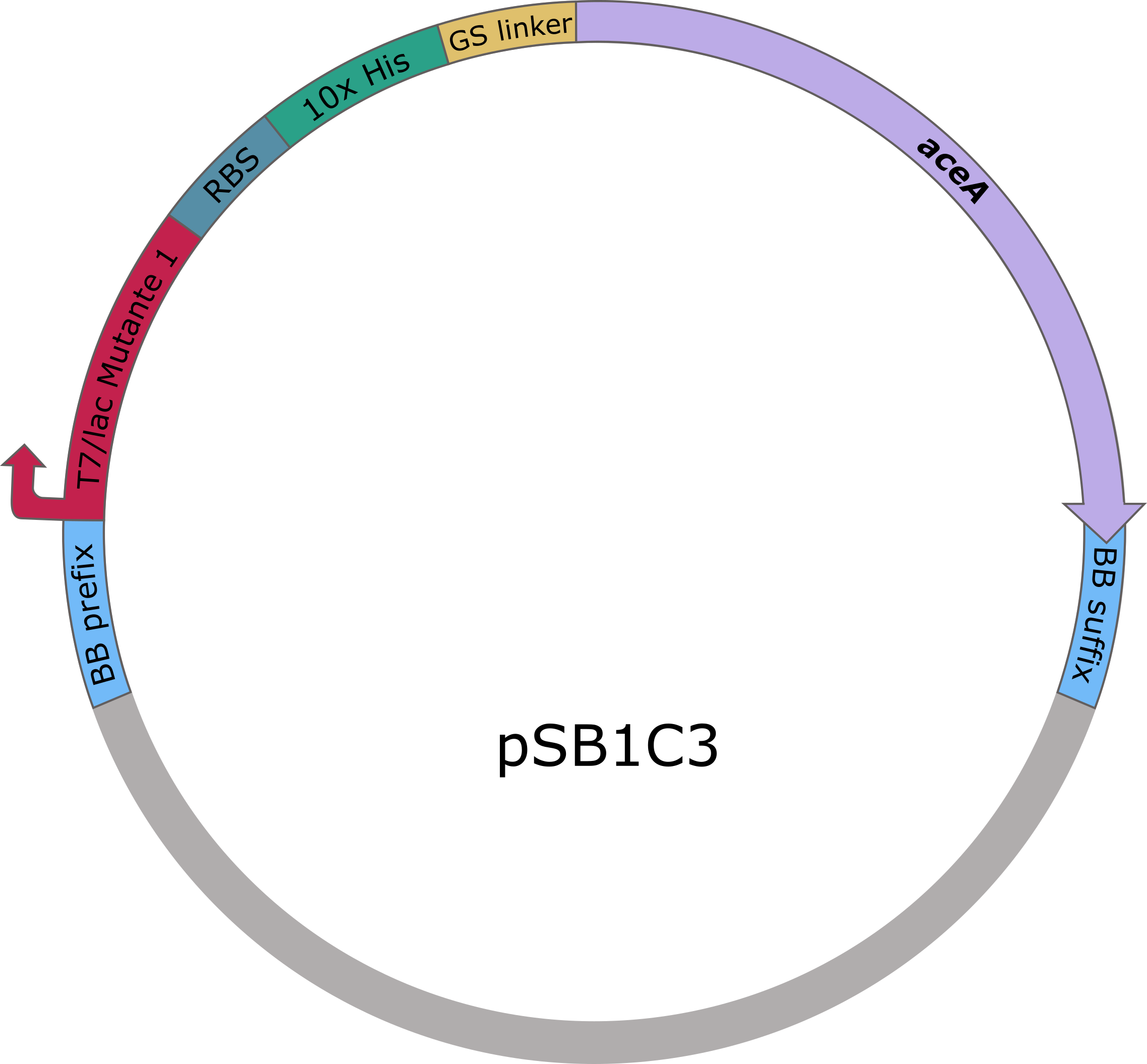

The sequences of aceA and ycdW were modified with a His-tag, ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and inserted into the pSB1C3 plasmid. For this purpose, the BioBrick assembly (BBa) was used. A T7 lac promotor (BBa_K921000) and a B0034-based ribosomal binding site (BBa_K2380024) were inserted upstream of the coding sequence via the BBa as well. E. coli TOP10 were transformed with generated plasmids and positive colonies were identified via colony PCR and DNA sequencing.

Figure 5 (left): pSB1C3 plasmid including expression cassette of aceA.

Figure 6 (right): pSB1C3 plasmid including expression cassette of ycdW.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

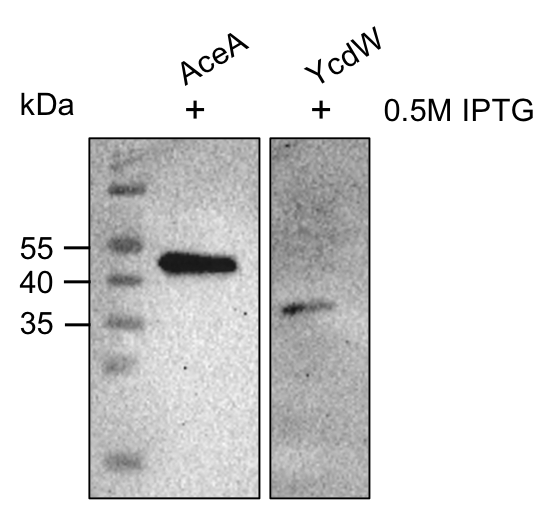

To verify that AceA and YcdW were produced, a SDS-PAGE was performed, followed by a western blot. The resulting bands were compared to the molecular weight of AceA and YcdW.

Purification

After production of AceA and YcdW in E. coli BL21 by induction of the T7 lac promotor with IPTG, an ÄKTA chromatography system (GE Healthcare, Illinois, USA) was used to purify the desired His-tagged enzymes.

Enzyme Assays

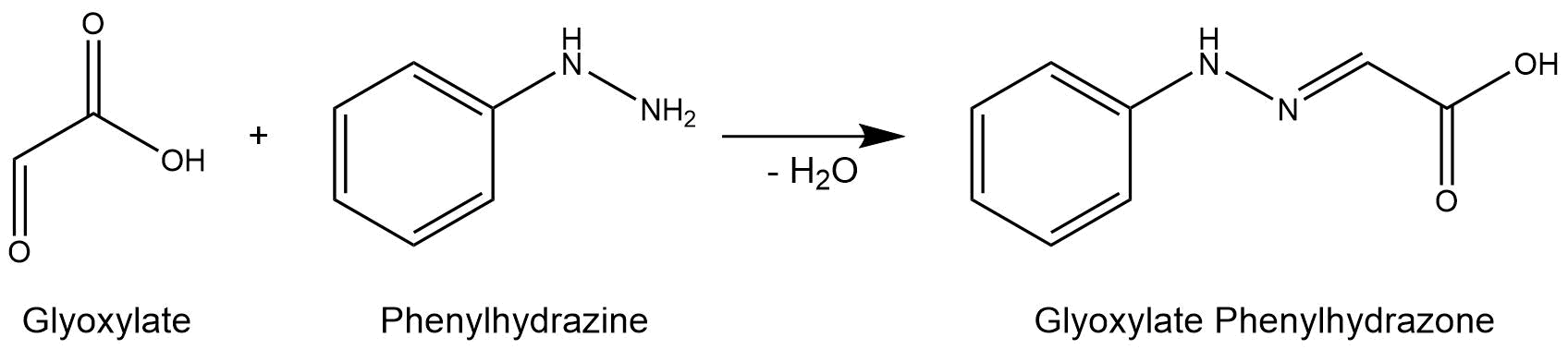

The purified enzymes were spectrophotometrically assayed for their activity using a plate reader. For the assay of the isocitrat lyase (AceA), the enzyme activity was tested via a phenylhydrazine-dependent reaction. As soon as AceA converts isocitrate into glyoxylate, the product reacts with phenylhydrazin to glyoxylate-phenylhydrazone, which possesses an absorption maximum at 324 nm. The change in absorption at 324 nm was measured over time. A calibration curve was created to calculate the glyoxylate-phenylhydrazone conversion rate. Therefore, the absorption of different concentrations of glyoxylate and phenylhyrazine was used.[3]

Figure 7: Reaction mechanism of phenylhydrazine-dependent assay for the verification of AceA enzyme activity.

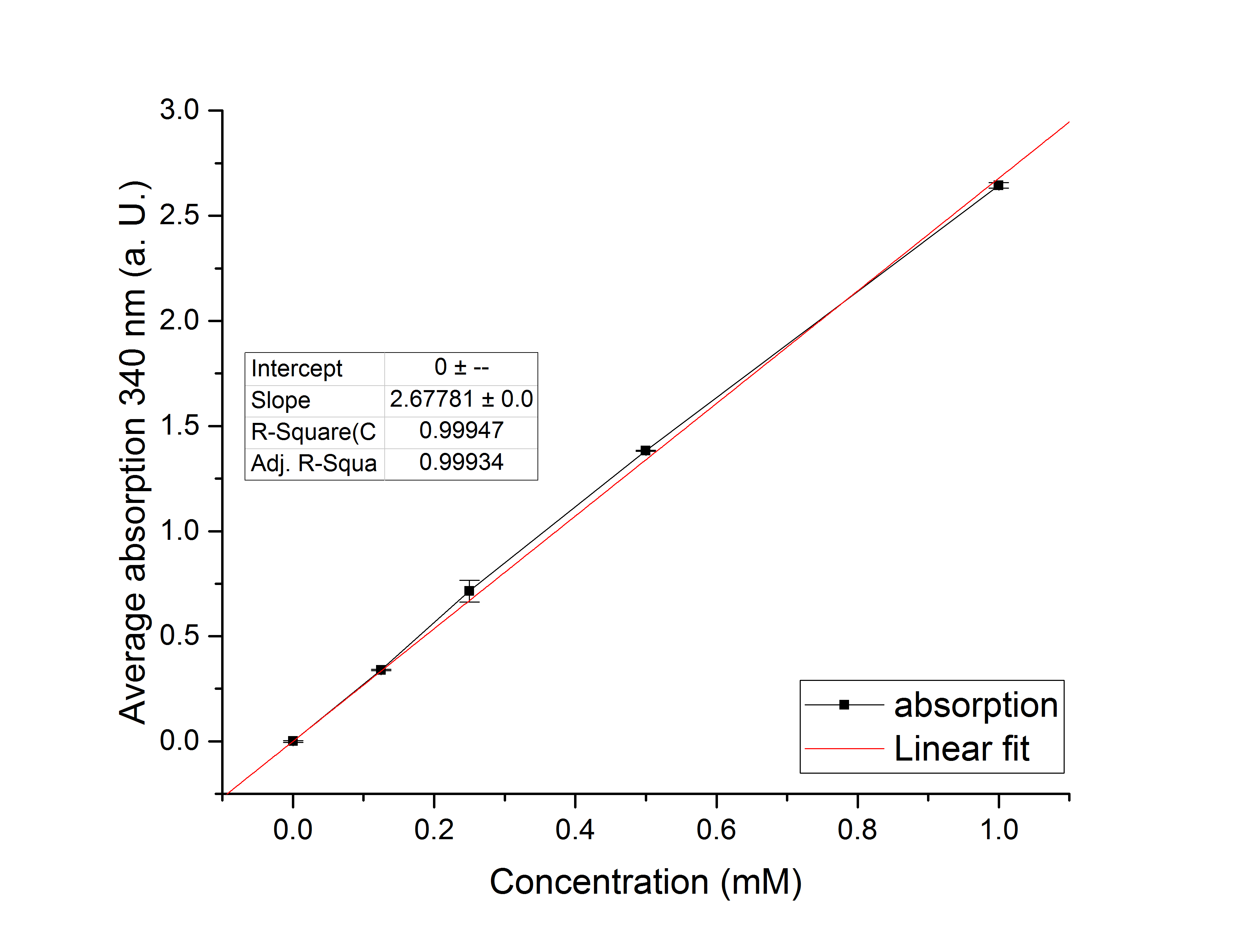

The assay for the glyoxylate reductase YcdW is based on the different absorption maxima of NADPH (absorption maxima at 260 nm and 340 nm) and NADP+ (maximum at 260 nm). During the reaction the enzyme uses NADPH as a cofactor. NADPH is converted into NADP+ which leads to a decrease of absorption at 340 nm. By measuring the absorption level at 340 nm over time, it is possible to quantify the enzyme activity and glycolic acid production. A calibration curve was created to calculate the NADPH conversion rate. Therefore, the absorption of different NADPH concentrations was measured.[4]

Figure 8: Reaction mechanism of NADPH-dependent conversion of glyoxylate into glycolic acid performed by YcdW.

HPLC Analysis

To detect the produced monomer glycolic acid, as well as the precursors, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was employed. An organic acid separation column as stationary phase and sulfuric acid as mobile phase allowed the separation of isocitrate, glyoxylate and glycolic acid. Signals were recorded by a refractive index detector.

M9 Growth Assay

The growth of E. coli BL21 transformed with an YcdW-generating plasmid was studied in M9 minimal media with and without a supplemented carbon source. M9 minimal medium consists of numerous salts to achieve an isotonic environment, but no carbon source. Hence, bacterial growth in M9 minimal media is inhibited. However, by supplementing either glucose, glyoxylate or glycolic acid in M9 media, the potential metabolization of these compounds of interest as a carbon source can be investigated. Therefore, the OD600 of E. coli cultures with the different carbon sources of interest were measured over a period of four days and compared to a carbon source-deficient culture.

Results and Discussion

Cloning and Expression

The aceA and the ycdW genes were cloned using E. coli TOP 10. Furthermore, the plasmids were successfully introduced into BL21 cells to enable protein production under the control of an IPTG inducible T7-lac promotor (BBA_K921000). An attached His-tag was used to purify the encoded enzymes via an ÄKTA system. The subsequent SDS-PAGE showed bands of the expected protein sizes. We also proved the successful production and purification of the enzymes via western blot (Figure 9). The expected molecular weights were 47.5 kDa for AceA and 35.3 kDa for YcdW, respective bands could be detected on the western blot.

Figure 9: Western blot analysis of purified proteins AceA & YcdW. Thermo Scientific PageRuler Prestained Protein Ladder was used. The nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with an anti-His antibody. For protein detection, a mouse anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with a horseradish-peroxidase was used.

As seen in figure 9, the western blot shows the expected signals. This indicates the successful purification and production of AceA and YcdW in E. coli. Hence, we started the protein characterization via in vitro enzyme assays.

AceA Enzyme Assay

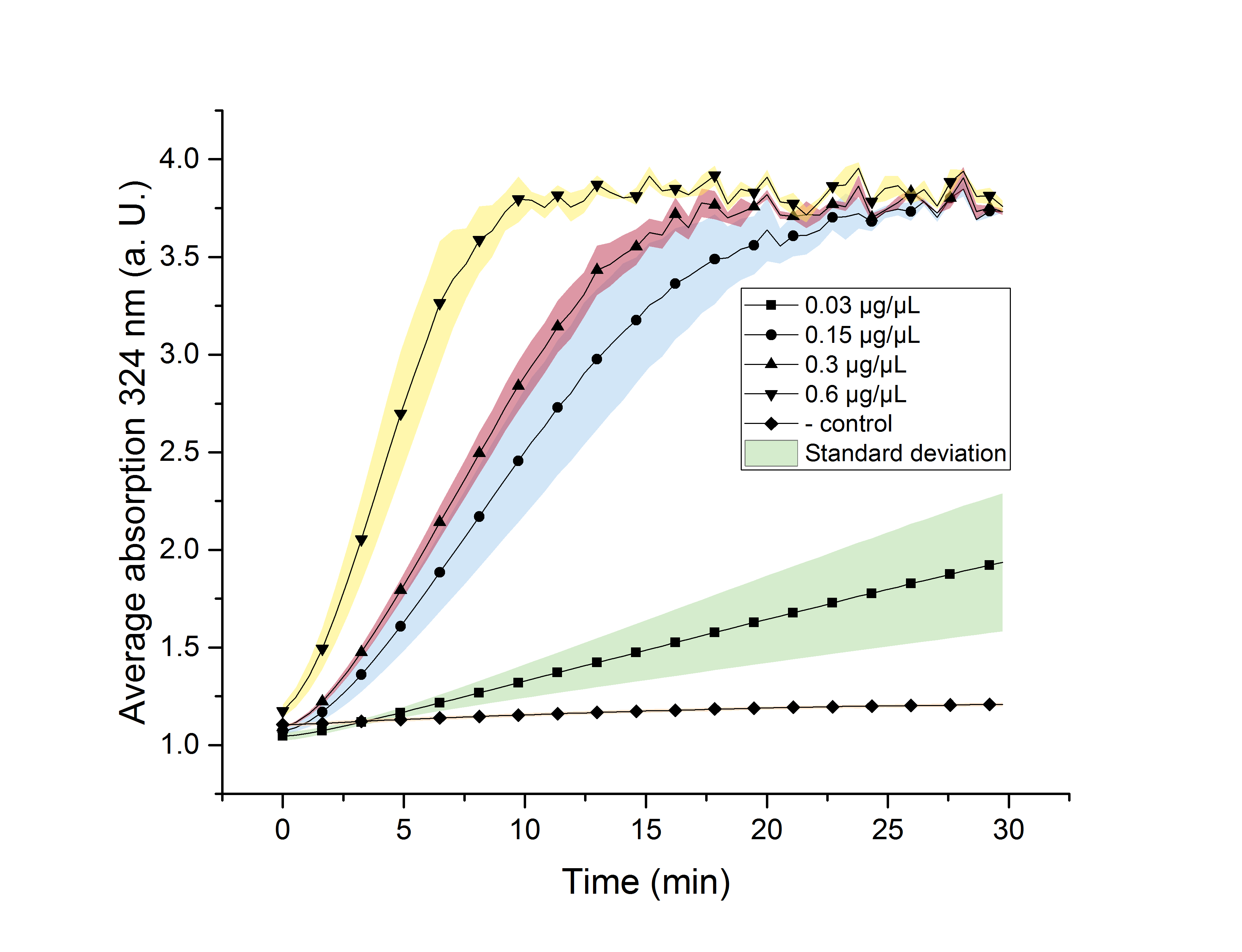

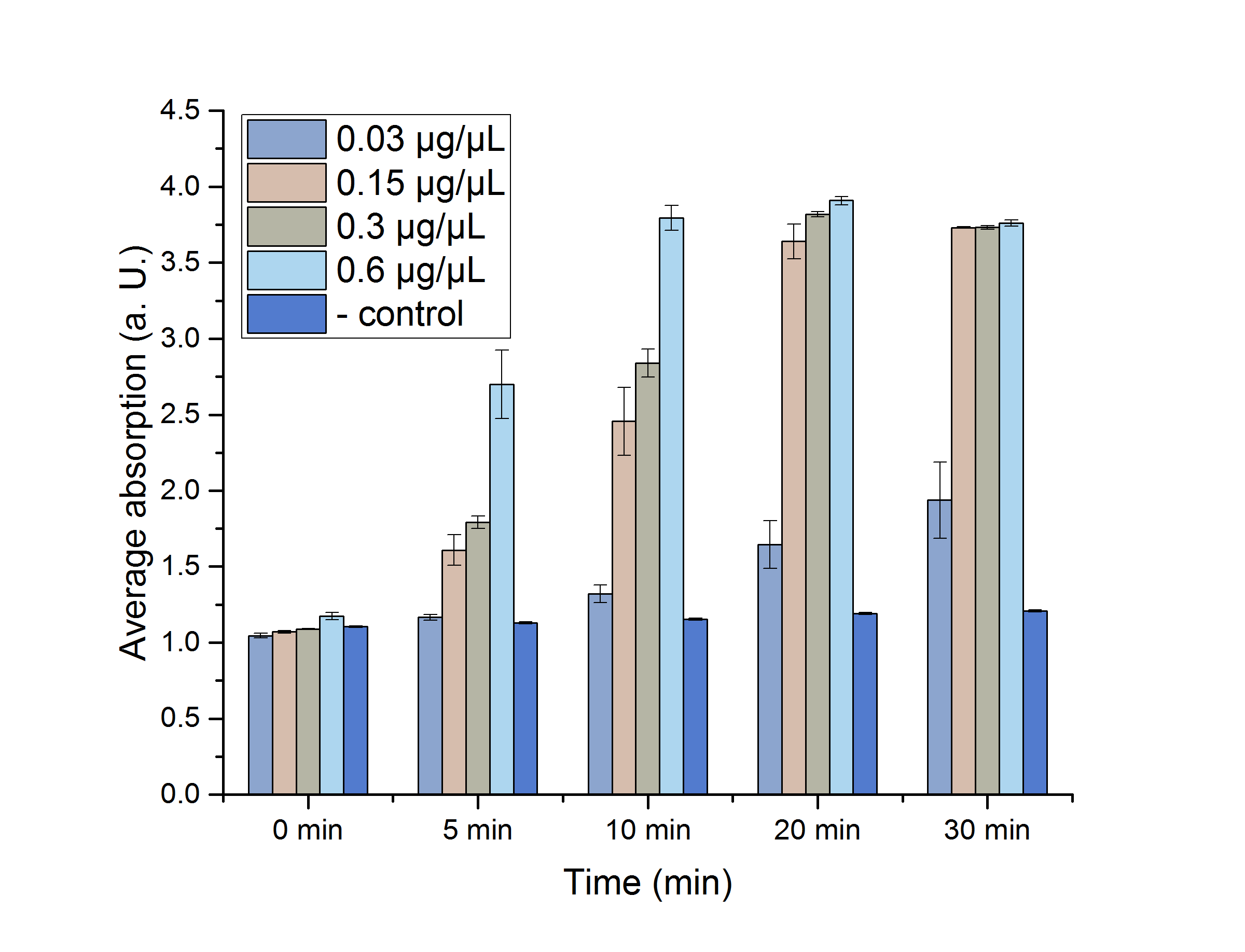

We verified the enzyme activity of AceA via a phenylhydrazine-dependent assay with the collected protein fractions from the ÄKTA purification. Isocitrate was included as a substrate. By adding phenylhydrazine to the reaction, glyoxylate produced during the assay (reaction time of 30 minutes) will further react to glyoxylate-phenylhydrazone, which absorbs light at a wavelength of 324 nm (see methods). Hence, we were able to indirectly measure glyoxylate production over time. We also included a negative control without enzyme, which is expected to stay on a constant absorption level, because no isocitrate is converted into glyoxylate. We used different enzyme concentrations (0.03 µg/µL; 0.15 µg/µL; 0.3 µg/µL; 0.6 µg/µL) and temperatures (21 °C/25 °C/37 °C) to screen for the best conditions.

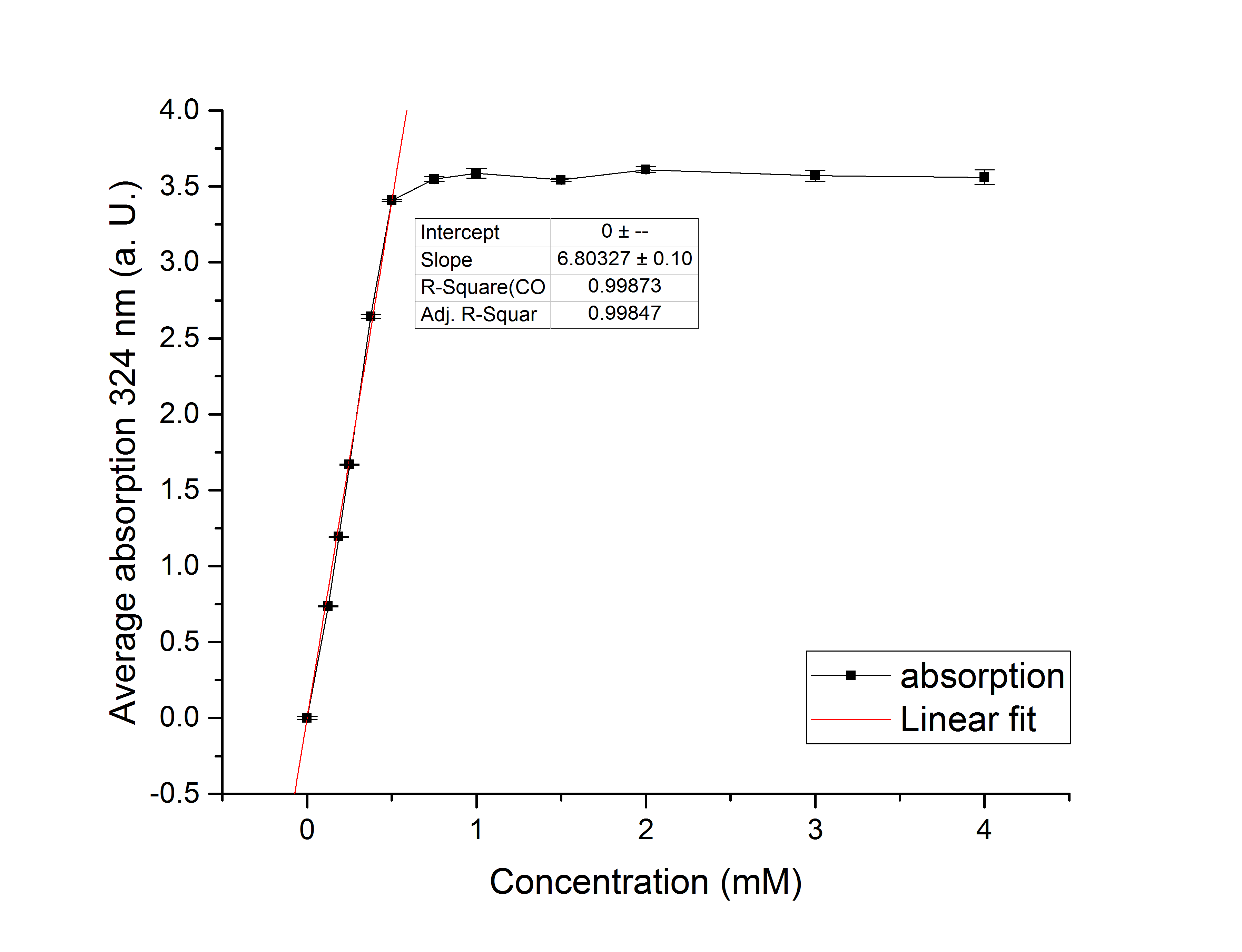

Referring to Robertson et al. [3], we first carried out assays with different enzyme concentrations at 25 °C. Figure 10 shows the calibration curve for the AceA assay, which is used to calculate the substrate turnover per time. To create the calibration curve, the absorption of different glyoxylate-phenylhydrazone concentrations was measured and compared to the resulting assay absorptions (Figure 11). For the AceA enzyme assay it was expected that a higher concentration would result in a faster substrate conversion.

Figure 10 (left): Calibration curve for AceA enzyme assay with different glyoxylate concentrations (0 mM, 0.125 mM, 0.1875 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.375 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.75 mM, 1 mM, 1.5 mM, 2 mM, 3 mM and 4 mM).

Figure 11 (right): AceA enzyme assay at 25 °C and 324 nm. The graph shows the average absorption in correlation to the time (min). Reactions with different enzyme concentration were measured, as well as a negative control sample without enzyme.

All used samples reach an absorption (324 nm) of approximately 3.7, but with different substrate conversion rates. Higher absorption values than 3.7 are not detectable by the plate reader. Hence, it is not possible to determine the exact yield. The negative control stays on a constant absorption level, which indicates that the increase in absorption of the enzyme containing samples is based on enzymatic activity. As expected, figure 11 shows that a higher enzyme concentration leads to a faster turnover of glyoxylate. The highest concentration of 0.6 µg/µL results in a substrate conversion rate of 0.912 µM/s. Thus, we decided to carry out further analysis regarding the optimal temperature with an enzyme concentration of 0.6 µg/µL.

To study the enzyme activity at different temperatures, we next performed the assay at 21 °C and 37 °C. The substrate conversion per time (µM/s) is shown in table 1. To achieve this, the substrate conversion values were recorded in the linear range of the particular curve in a time frame of 3.5 minutes. It should be noted that the determination does not start at the exact same time for all samples, but the time frame of 3.5 minutes was retained. Three replicates were measured for every assay.

Table 1: Substrate conversion of AceA per time (µM/s) in correlation to different temperatures (21 °C, 25 °C and 37 °C).

| Temperature [°C] | Substrate conversion

per second [µM/s] |

|---|---|

| 21 | 0.82 |

| 25 | 0.912 |

| 37 | 0.914 |

Table 1 shows that the enzyme performs best at a temperature of 25 °C and 37 °C with a substrate conversion of 0.912 µM/s and 0.914 µM/s. At a temperature of 21 °C the enzyme shows its lowest conversion rate of 0.82 µM/s.

Referring to Robertson et al. [3] a temperature of 25 °C was used for further analysis.

A Student's t-test was performed to check the significance of our data. For this test, five data points from the 25 °C assay were chosen (0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes) and plotted in figure 12 for a better visualization.

Figure 12: AceA assay absorption for 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes with standard error. n=3

The absorptions, as well as the particular standard errors, are also shown in table 2. Significance is indicated by *.

Table 2: Calculated significance of AceA data sets for 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes, 25 °C. The table also shows the absorption as well as the particular standard error. A= Absorption, *= Significance (p-value < 0.05). n= 3.

| AceA [µg/µL] | A (t=0 min) | A (t=5 min) | A (t=10 min) | A (t=20 min) | A (t=30 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 1.046±0.016* | 1.665±0.018 | 1.32±0.058 | 1.645±0.258 | 1.937±0.249 |

| 0.15 | 1.071±0.009* | 1.609±0.1* | 2.456±0.222* | 3.639±0.114* | 3.732±0,003* |

| 0.3 | 1.089±0.003 | 1.793±0.04* | 2.84±0.091* | 3.19±0.017* | 3.732±0.012* |

| 0.6 | 1.175±0.023 | 2.698±0.225* | 3.795±0.083* | 3.909±0.027* | 3.759±0.02* |

| neg. | 1.105±0.005 | 1.13+0.007 | 1.154+0.007 | 1.191±0.006 | 1.209±0.006 |

As shown in table 2, most of the data points show a p-value < 0.05, which indicates that the data is significant. Non-significant p-values appear in the data set of the lowest enzyme concentration.

After the characterization of the in vitro enzyme activity, the production of glyoxylate was analyzed via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

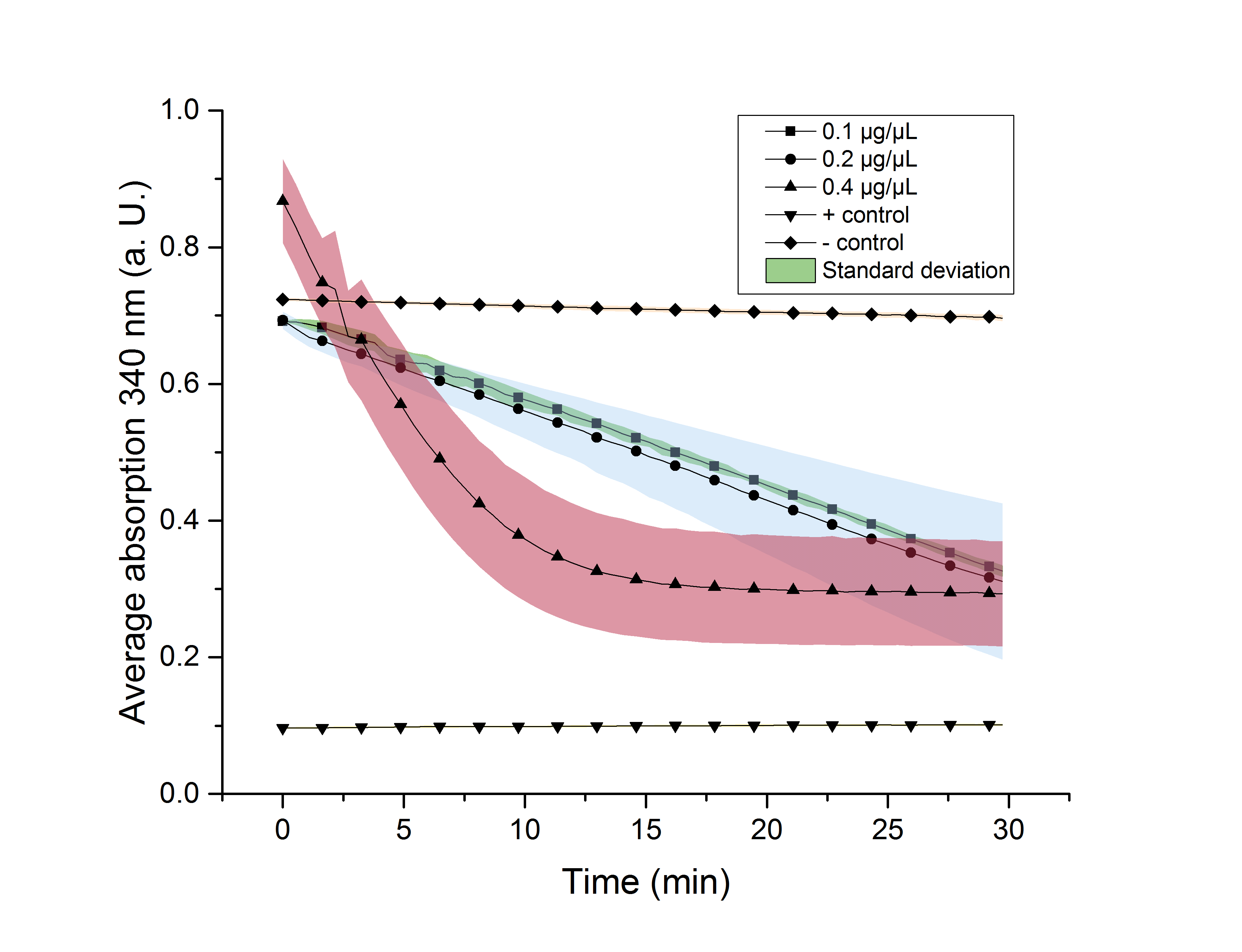

YcdW Enzyme Assay

We verified the enzyme activity of YcdW via a NADPH assay with the collected protein fractions from the ÄKTA purification. YcdW oxidizes NADPH to reduce glyoxylate to glycolic acid. NADPH absorbs light at a wavelength of 340 nm, but NADP+ does not. Hence, the absorbance at 340 nm decreases when YcdW is actively turning glyoxylate into glycolic acid. In this experiment we included a positive control, which consisted of NADP+ with enzyme as well as a negative control, including NADPH without enzyme. For both the positive and negative control it was expected, that they stay on a constant absorption level. For the negative control, containing NADPH without the desired enzyme, the absorption should stay constant because no NADPH should be converted into NADP+. For the positive control, containing NADP+, the absorption is expected to stay on a constant absorption level, which should be lower than the absorption for NADPH at a wavelength of 340 nm. Different enzyme concentrations (0.1 µg/µL; 0.2 µg/µL; 0.4 µg/µL) and temperatures (21 °C/25 °C/37 °C) were tested to find optimal assay conditions.

Referring to Nuñez et al. [4], we carried out assays with different enzyme concentrations at 25 °C. Figure 13 shows the calibration curve for the YcdW assay, which is used to calculate the substrate turnover per time. To create the calibration curve, the absorption of different NADPH concentrations was measured and compared to the resulting assay absorptions (Figure 14). For the YcdW assay, it was expected that a higher enzyme concentration would result in a faster substrate conversion.

Figure 13 (left): Calibration curve for YcdW enzyme assay with different NADPH concentrations (1 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.125 mM and 0 mM).

Figure 14 (right): NADPH dependent enzyme assay of YcdW at a temperature of 25 °C. The graph shows the average absorption at 340 nm in correlation to the time (min). Different enzyme concentration were used, as well as a postive (NADP+) and negative control (NADPH without enzyme).

As expected, figure 14 shows that a higher enzyme concentration leads to a faster turnover of glyoxylate. The highest concentration of 0.4 µg/µL reaches an absorption of 0.29 after approximately 15 minutes, which equals a total substrate conversion rate of 0.345 µM/s. Hence, we decided to carry out further analysis regarding the optimal temperature with an enzyme concentration of 0.4 µg/µL. The positive and negative control both stayed on a constant absorption level, which indicates that the absorption decrease of the enzyme containing samples is based on enzymatic activity. However, figure 14 also shows that the enzyme does not reach the level of the positive control, which is presumably due to residual NADPH in the sample. A possible reason could be a too small amount of glyxoylate when starting the assay.

To study the enzyme activity at different temperatures we performed the assay at 21 °C and 37 °C. The substrate conversion per time (µM/s) is shown in table 3. Therefore, the substrate conversion values were recorded in the linear range of the particular curve in a time frame of 3.5 minutes. It should be noted that the determination does not start at the exact same time for all samples, but the time frame of 3.5 minutes was retained. Three replicates were measured for every assay.

Table 3: Substrate conversion of YcdW per time (µM/s) in correlation to different temperature (21 °C, 25 °C and 37 °C).

| Temperature [°C] | Substrate conversion

per second [µM/s] |

|---|---|

| 21 | 0.31 |

| 25 | 0.345 |

| 37 | 0.26 |

Table 3 shows that the enzyme performs best at a temperature of 25 °C with a substrate conversion of 0.345 µM/s, followed by a conversion rate of 0.31 µM/s at 21 °C. At a temperature of 37 °C the enzyme shows its lowest conversion rate of 0.26 µM/s.

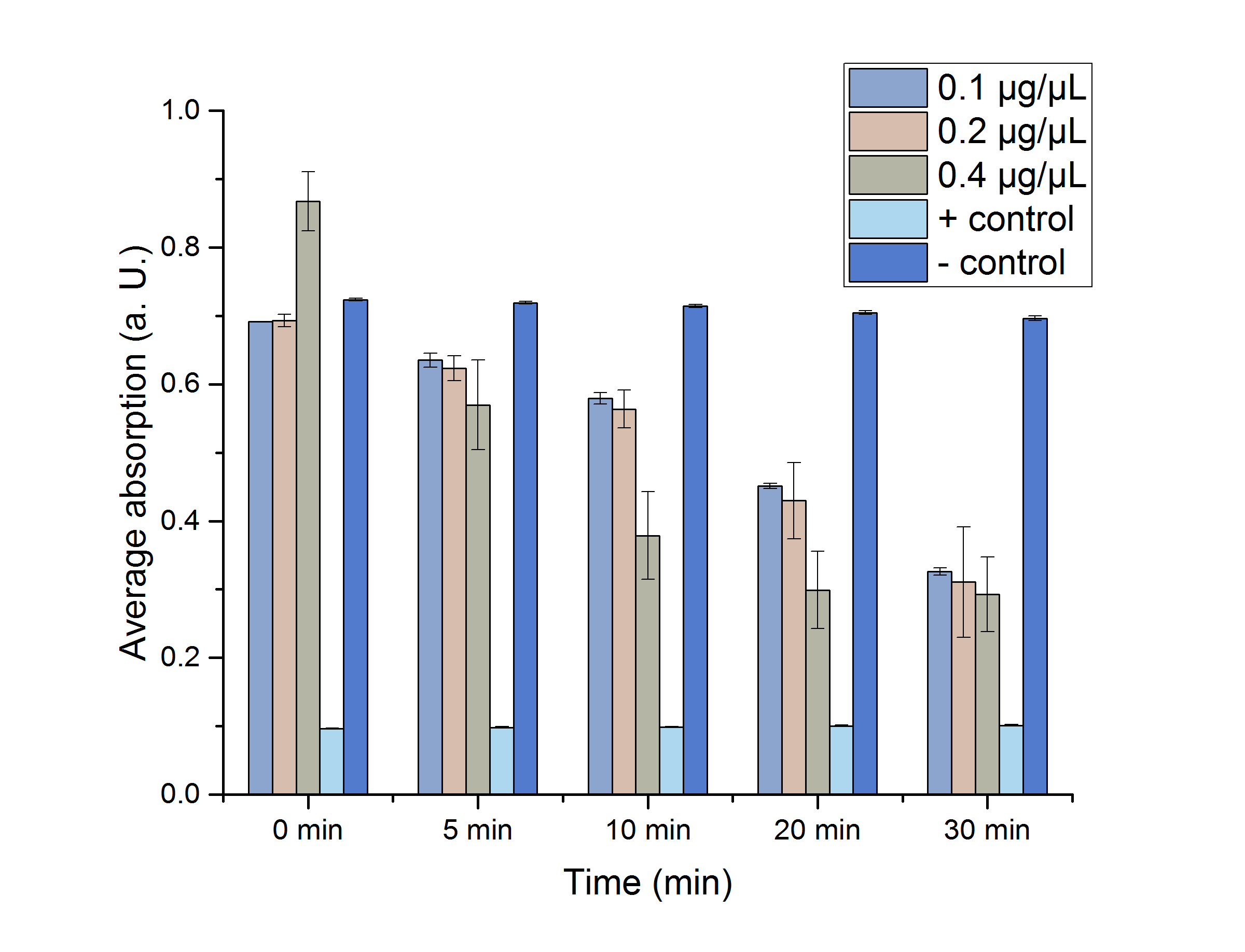

After showing that YcdW performs best at a temperature of 25 °C, a Student's t-test was performed to check the significance of our data. Five different data sets (0, 5, 10, 20, 30 min) were chosen. For a better visualization the data sets were plotted (Figure 15).

Figure 15: YcdW assay absorption for 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes with standard error. n=3

The absorptions and corresponding standard errors are also shown in table 4. Significance is indicated by *.

Table 4: Calculated significance of YcdW data sets for 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes, 25 °C. The table also shows the NADPH-absorption as well as the particular standard error. A= Absorption, *= Significance (p-value < 0.05), n= 3.

| YcdW [µg/µL] | A (t=0 min) | A (t=5 min) | A (t=10 min) | A (t=20 min) | A (t=30 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.691±0.0003* | 0.635±0.01* | 0.58±0.008* | 0.451±0.004* | 0.326±0.005* |

| 0.2 | 0.693±0.009 | 0.623±0.018* | 0.563±0.028* | 0.429±0.056* | 0.31±0.08* |

| 0.4 | 0.868±0.043 | 0.57±0.07 | 0.38±0.064* | 0.3±0.06* | 0.293±0.054* |

| pos. | 0.096±0.0008* | 0.098±0.001* | 0.099±0.001* | 0.1±0.001* | 0.101±0.001* |

| neg. | 0.724±0.0017 | 0.719±0.002 | 0.714±0.002 | 0.705±0.003 | 0.696±0.003 |

As shown in table 4, most of the data points show a p-value < 0.05, which indicates that the data is significant.

The results show clearly that the glyoxylate reductase YcdW performs best at 25 °C and the highest concentration of 0.4 µg/µL, which allows a further characterization of the reaction and production of the desired monomer glycolic acid via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

HPLC Analysis

In order to verify the production of glycolic acid (product of YcdW) and its precursor glyoxylate (product of AceA) HPLC was employed. Therefore, three in vitro assays were performed as described in section 1.3.4. For the YcdW assay, previous HPLC-analysis showed a low conversion rate of gyloxylate into glycolic acid, which indicated a NADPH-shortage. Hence, NADPH was used in a higher concentration. Additionally an in vitro assay, containing both enzymes was carried out in the YcdW reaction buffer to analyze the simultaneous performance of both enzymes, starting from isocitrate as a substrate. In order to analyze the in vivo production of glycolic acid, ycdW-transformed E. coli cells were disrupted and centrifuged. The supernatant was sterile-filtered and analyzed. In total, four samples were analyzed via HPLC:

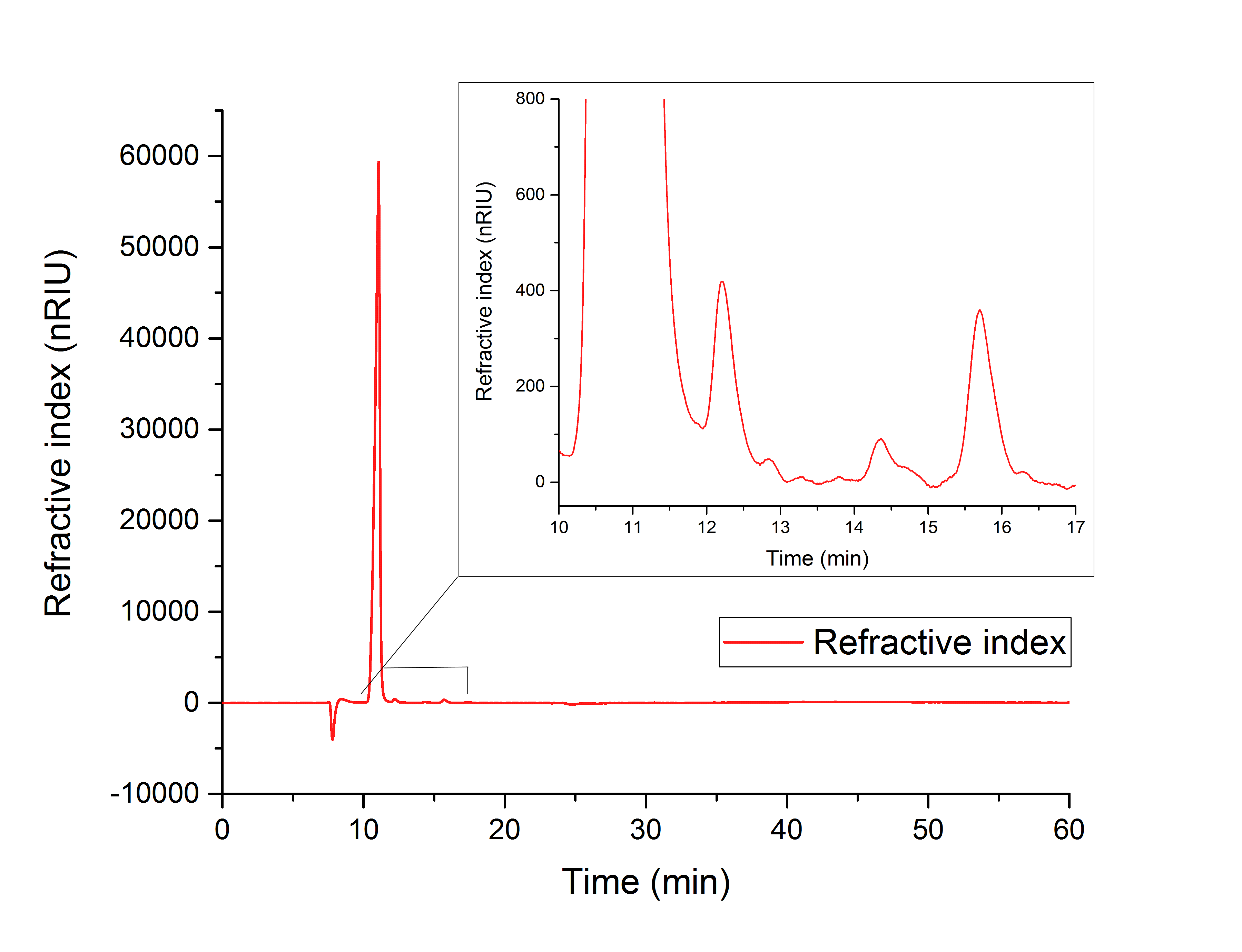

1. In vitro YcdW assay with NADPH surplus (Figure 16)

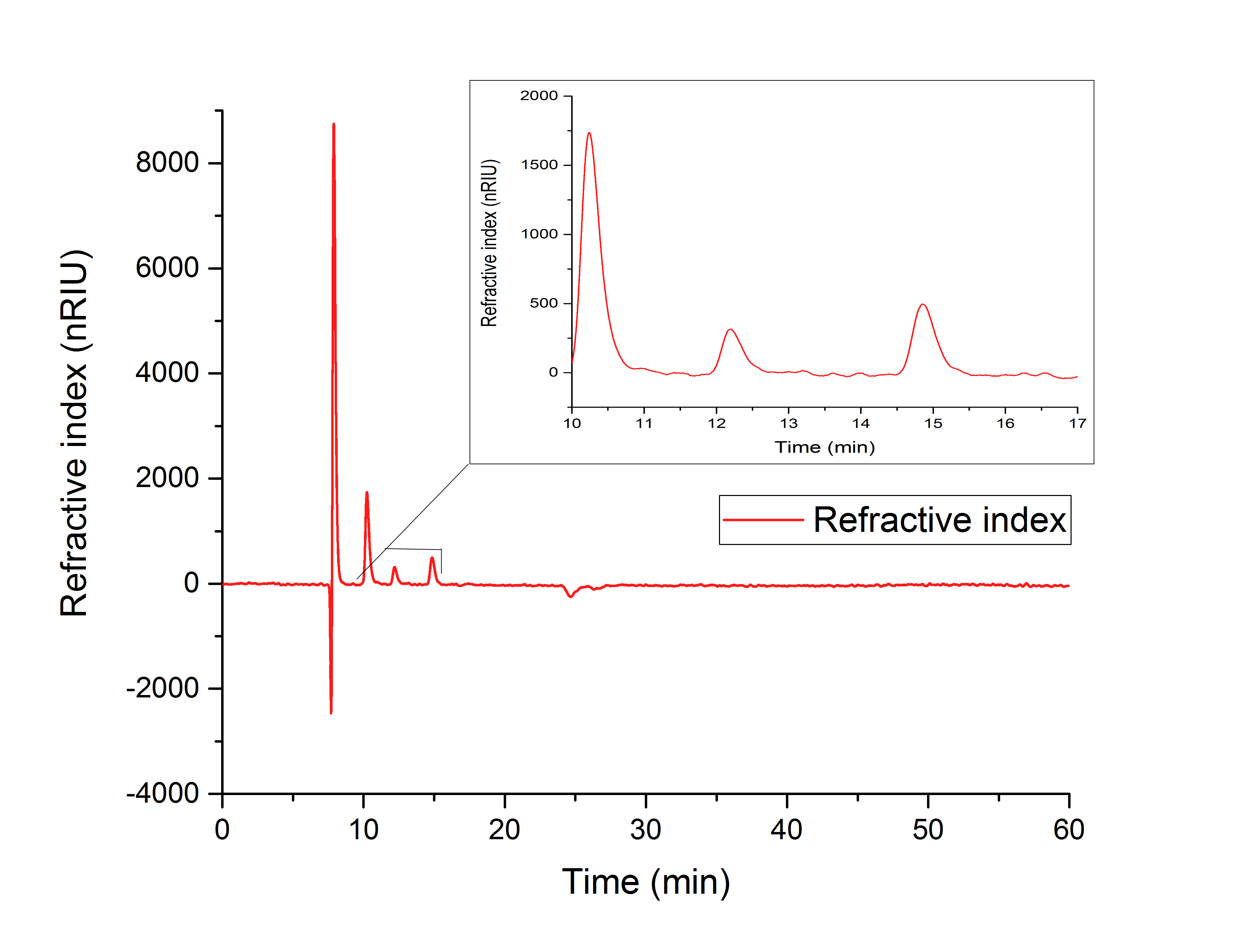

2. In vitro AceA assay (Figure 17)

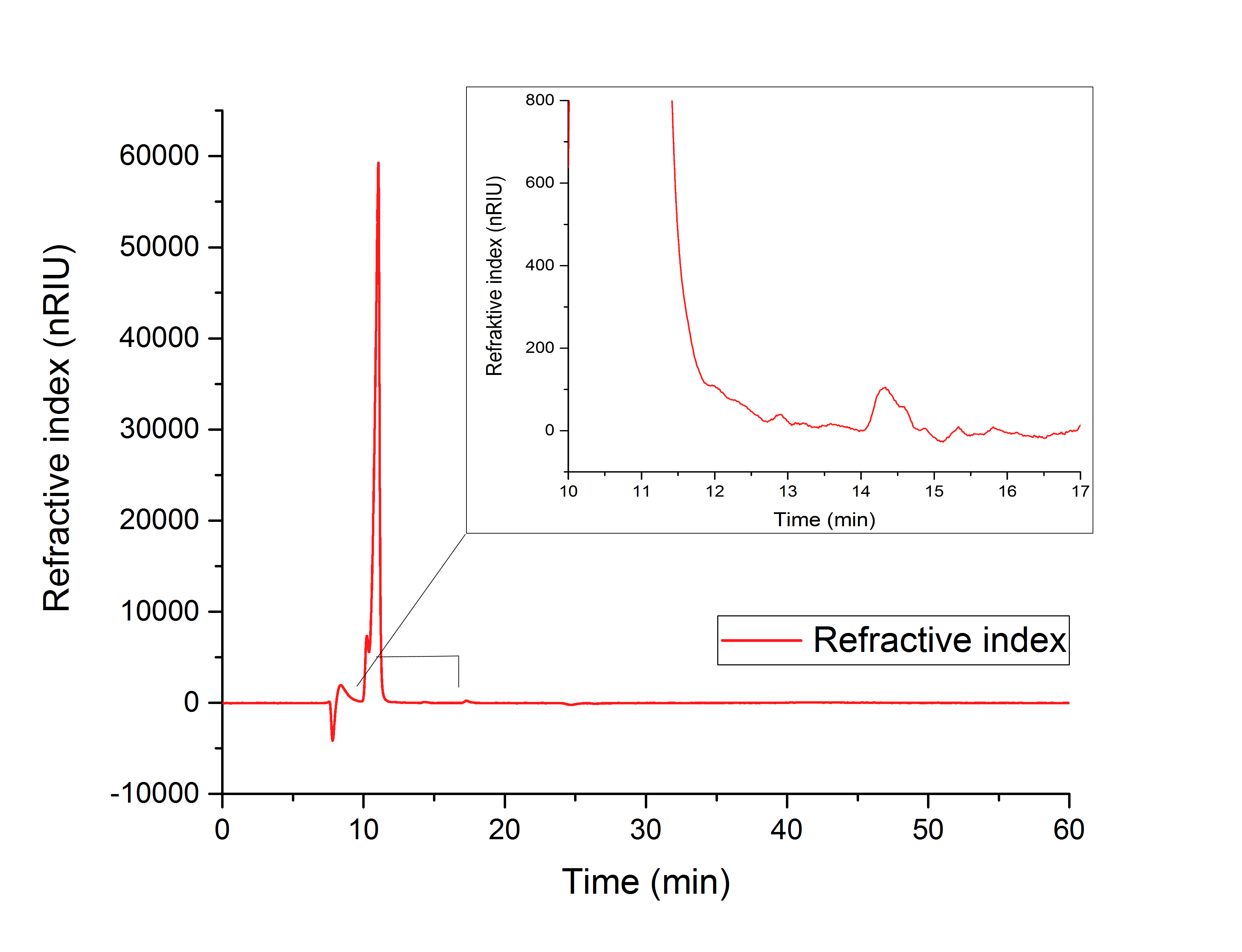

3. In vitro YcdW with AceA in YcdW reaction buffer (Figure 18)

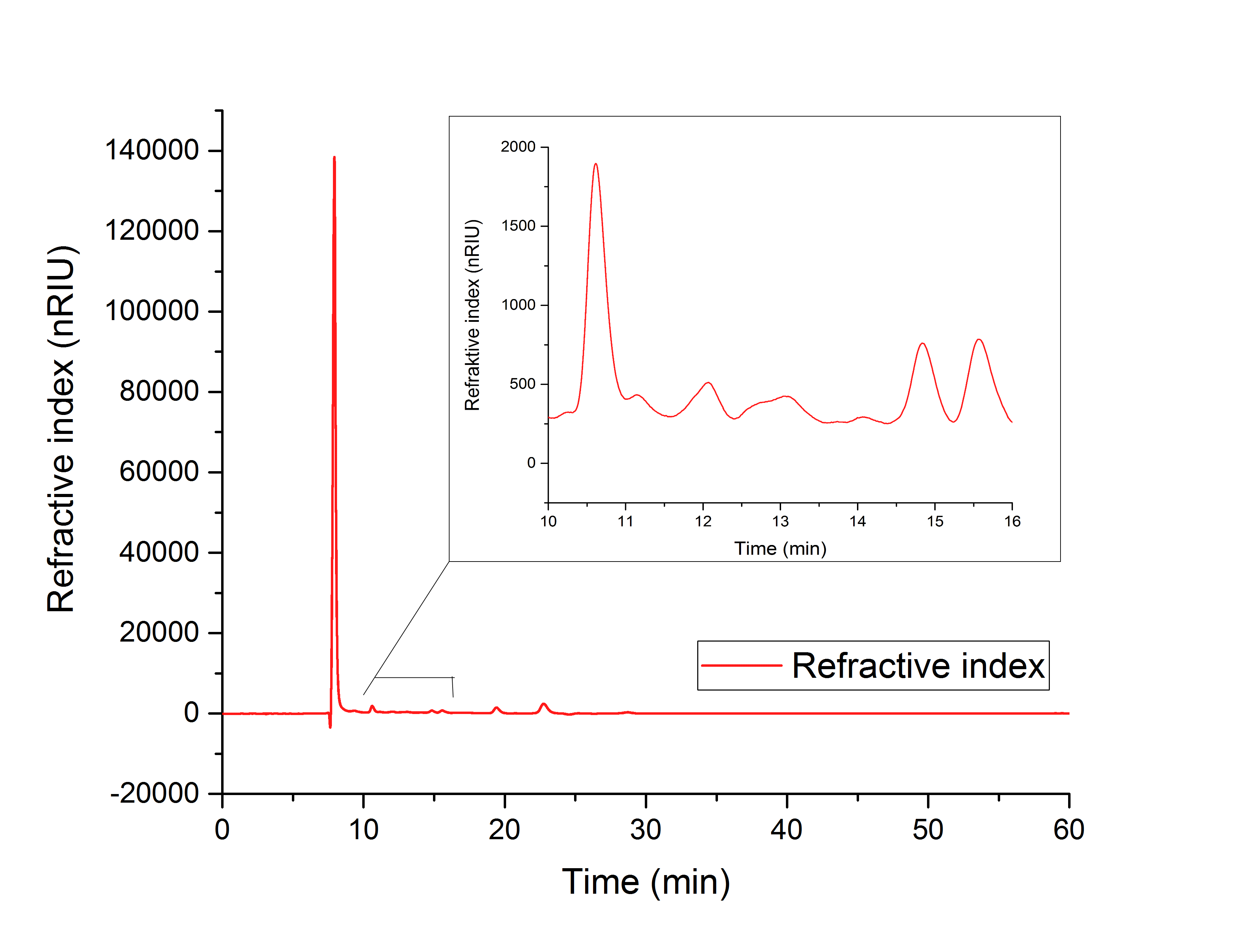

4. Analysis of disrupted ycdW-transformed E. coli (Figure 19)

To compare the resulting retention times from our samples, we used external references, which showed the following retention times:

1. Isocitrate: 10.25 min

2. Glyoxylate: 12.193 min

3. Glycolic acid: 15.749 min

For assay 1 (in vitro YcdW assay) a peak after 15.701 minutes confirms the production of glycolic acid from glyoxylate (12.210 min, Figure 16).

Figure 16: HPLC analysis of YcdW in vitro enzyme assay with NADPH surplus. Glycolic acid peak can be seen at 15.701 minutes and glyoxylate peak at 12.210 minutes.

Figure 17 (in vitro AceA assay) indicates the production of glyoxylate with a retention time of 12.195 minutes from isocitrate (10.240 min).

Figure 17: HPLC analysis of AceA in vitro assay. Production of glyoxylate is indicated by a peak at 12.195 min. The results show a peak at 10.240 minutes, which correlates to isocitrat.

While testing the parallel performance of YcdW and AceA, a white precipitate was noticed. Since the HPLC (Figure 18) shows no peaks for neither glyoxylate nor glycolic acid, it is likely that AceA precipitated in the YcdW reaction buffer (potassium phosphate), resulting in a loss of catalytic activity.

Figure 18: HPLC analysis of in vitro assay containing both desired enzymes in the YcdW reaction buffer. No expected retention times can be seen.

The cell lysate (Figure 19) shows, besides others, peaks corresponding to the retention time of glyoxylate (12.066 min) and glycolic acid (15.568 min).

It can therefore be concluded that the production of glycolic acid in E. coli was successful.

Figure 19: HPLC analysis of supernatant of disrupted ycdW-transformed E. coli. Glyoxylate and glycolic acid peaks can be seen at 12.066 and 15.568 minutes.

The results show, that a simultaneous in vitro performance of both enzymes in the YcdW potassium phosphate buffer, starting from isocitrate as a substrate, does not result in the production of glycolic acid (Figure 19). To switch from a successive in vitro synthesis of glycolic acid to a simultaneous one, it is necessary to find an optimized buffer for maximum performance of both enzymes. The in vitro productions of glycolic acid and glyoxylate as well as the in vivo production of glycolic acid were successful (Figures 16, 17 and 18).

Growth Assay

To find out in which way the cloned plasmids (ycdW x pSB1C3 and aceA x pSB1C3) effect the growth efficiency of our expression strain E. coli BL21, we performed a growth assay. The results showed no significance. However, in other experiments, these cells showed no distinguishable difference in growth compared to non-transformed cells. Hence, we suspect that the overexpression of ycdW and aceA has no great influence on growth. To proof this hypothesis, further growth assays must be carried out.

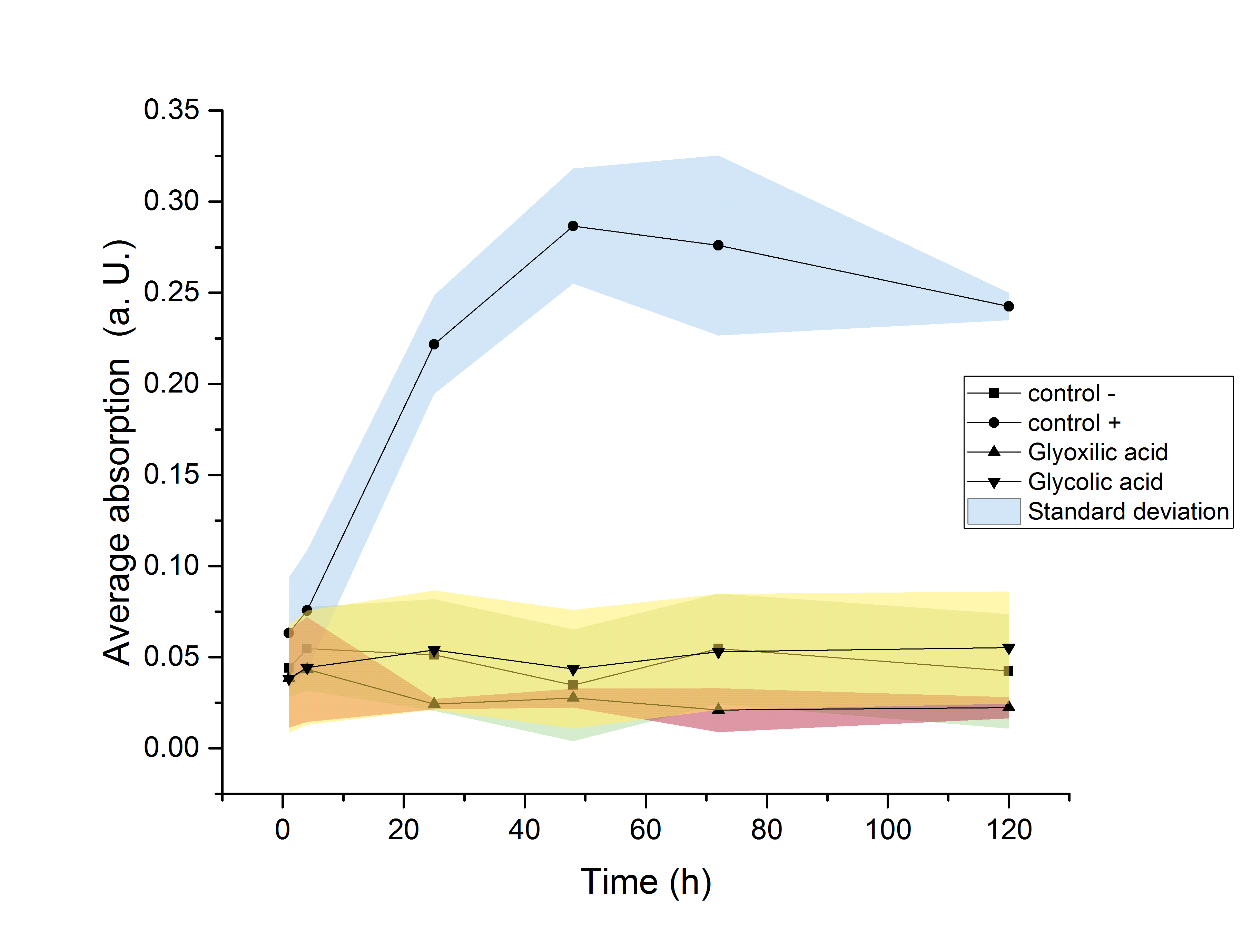

M9 Minimal Medium

The strain used for protein production (E. coli BL21) was investigated regarding its ability to use the produced monomers as a carbon source. Since this would result in a decrease of the desired product amount, it would be detrimental to this projects goal of providing monomers for polymerisation. Since E. coli show a significantly elongated lag phase when grown in M9 minimal medium (Paliy et al.[5]), the OD600 was measured over the course of 120 hours. An increase in the OD600 indicating growth of the culture was only observed in media supplemented with glucose. Since no growth was observed neither in glycolic acid nor in glyoxylate containing media, it can be concluded, that no significant degradation of the desired product is taking place.

Figure 20: Growth assay of ycdW-transformed E. coli in M9 minimal medium. Growth was only observed in media supplemented with glucose. No growth was observe neither in glycolic acid nor in glyoxylate containing media.

Outlook

We aimed for a more sustainable, environment-friendly production of glycolic acid, which can be used as component of the biodegradable polymer PLGA. To achieve this, we genetically engineered E. coli and demonstrated the in vivo and in vitro bioproduction of glycolic acid. Hence, our approach enables the future production of PLGA polymers independently from fossil resources.

However, to make this process profitable, production titers have to be increased. Therefore, we suggest the following optimization steps: Currently, we use a two-plasmid system, harboring the genes ycdW and aceA, to express the biosynthesis pathway in E. coli. To minimize the metabolic burden on E. coli, both enzymes shall be either encoded on one single plasmid or their genes shall be genomically integrated in E. coli. Furthermore, counteracting enzymes, e.g. aceB [6], lower the metabolite pool of our pathway and thereby decrease product titers. Hence, we suggest the deletion of such counteracting enzymes.

To further increase titers, it is possible to fine-tune the expression ratios of our genes, considering their enzyme activities, co-factor dependencies, titers of glycolic acid and the growth rate of E. coli. Several synthetic metabolic channeling approaches may also increase titers.[7][8]

For an enhanced in vitro production, we suggest the optimization of the reaction buffer, including its pH, to simultaneously use both key enzymes. We also see space for improvements in fine-tuning substrate and co-factor concentrations. To quantify the performance and output of our two approaches (in vivo and in vitro production), a quantitative analysis of our HPLC runs should be performed next. The first step towards this will be the creation of a calibration curve.

Considering all these aspects, we are optimistic that an optimized glycolic acid production in E. coli has the potential to replace the petrochemical-dependent PLGA production.

Team

Group picture of the "E. coli" team

From left to right: Elena Nickels, Maria Musillo, Benedict Spannenkrebs, Peter Gockel and Luca Brenker

References

- ↑ UniProtKB - P0A9G6 (ACEA_ECOLI), 10/14/2018 [1].

- ↑ UniProtKB - P75913 (GHRA_ECOLI), 10/14/2018 [2].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Eugene F. Roberston and Henry C. Reeves, Purification and characterization of isocitrate lyase from Escherichia coli, Current Microbiology Vol.14 (1987), pp. 347-350 [3].

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M. Felisa Nuñez, M. Teresa Pellicer, Josefa Badia, Juan Aguilar and Laura Baldoma, Biochemical characterization of the 2-ketoacid reductases encoded by ycdW and yiaE genes in Escherichia coli, Biochemical Journal, 2001, 354, 707-715 [4].

- ↑ Oleg Paliy and Thusitha S. Gunasekera, Growth of E. coli BL21 in minimal media with different gluconeogenic carbon sources and salt contents, Applied Microbiology Biotechnology, 2007, 73: 1169-1172 [5].

- ↑ UniProtKB - P08997 (MASY_ECOLI), 10/16/2018 [6].

- ↑ John E. Dueber, Gabriel C. Wu, G Reza Malmirchegini, Tae Seok Moon, Christopher J. Petzold, Adeeti V. Ullal, Kristala L. J. Prather and Jay D. Keasling, Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux, Nature Biotechnology, 27, pages 753–759 (2009) [7].

- ↑ Matthew J. Lee, Judith Mandell, Lorna Hodgson, Dominic Alibhai, Jordan M. Fletcher, Ian R. Brown, Stefanie Frank, Wei-Feng Xue, Paul Verkade, Derek N. Woolfson and Martin J. Warren, Engineered synthetic scaffolds for organizing proteins within the bacterial cytoplasm, nature chemical biology, 14, pages 142–147 (2018) [8].