Contents

PLGA

Abstract

There are two major methods for the synthesis of PLGA. The first method is the polycondensation reaction[1]. The second approach that we chose for our synthesis is the anionic ring opening polymerization (ROP). If the synthesis is performed using ROP we need a combination of an initiator and co-initiator to start a living polymerization. This has the advantage of producing higher molecular weights than the previous method, due to there is no release of water as a couple product. High molecular weights are important for our desired application. The downside of the ROP is that it can be killed by low amounts of impurities like present water. The reaction therefore has to be carried out under an inert gas atmosphere and impurities have to be removed before the reaction by applying a strong vacuum on the reaction vessel. This can be easily achieved by using a schlenk. The polymer is later analyzed via gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy[1].

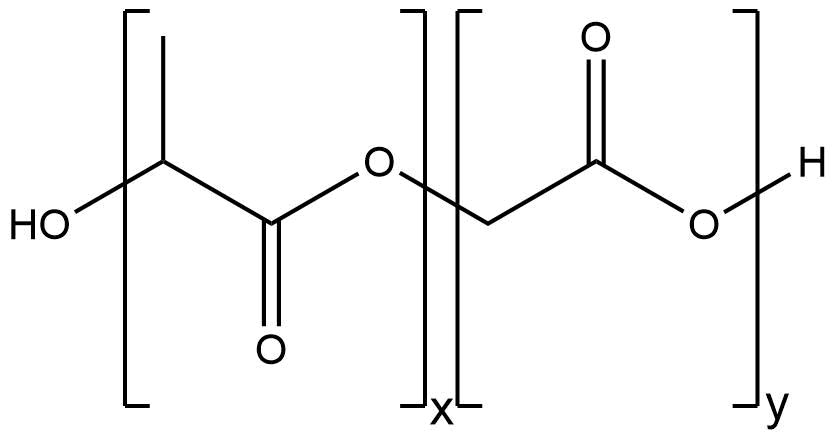

Figure 1: Structure of PLGA

The schlenk line

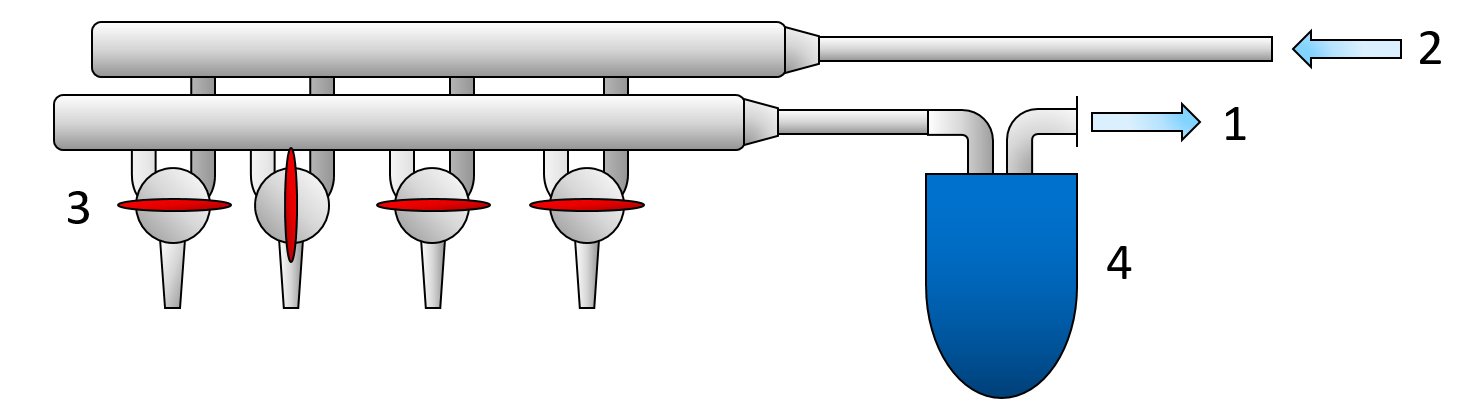

The schlenk line is a commonly used apparatus in chemical labs, that enables a quick change between pulling vacuum on the reaction vessel and applying an inert gas atmosphere. The change between inert gas and vacuum can occur in an instant by turning a special stopcock or a Teflon tap. The vacuum is applied using a vacuum pump. The pump has to be protected by an ice trap, that condenses any escaping moisture from the reaction vessel to prevent damage to the vacuum pump (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Illustration of a schlenk line. 1 connection to the vacuum pump. 2 connection to the inertgas source. 3 Stopcocks or a Teflon tap. 4 Ice trap.

Synthesis of PLGA

Mechanism of the Anionic Ring Opening Polymerization

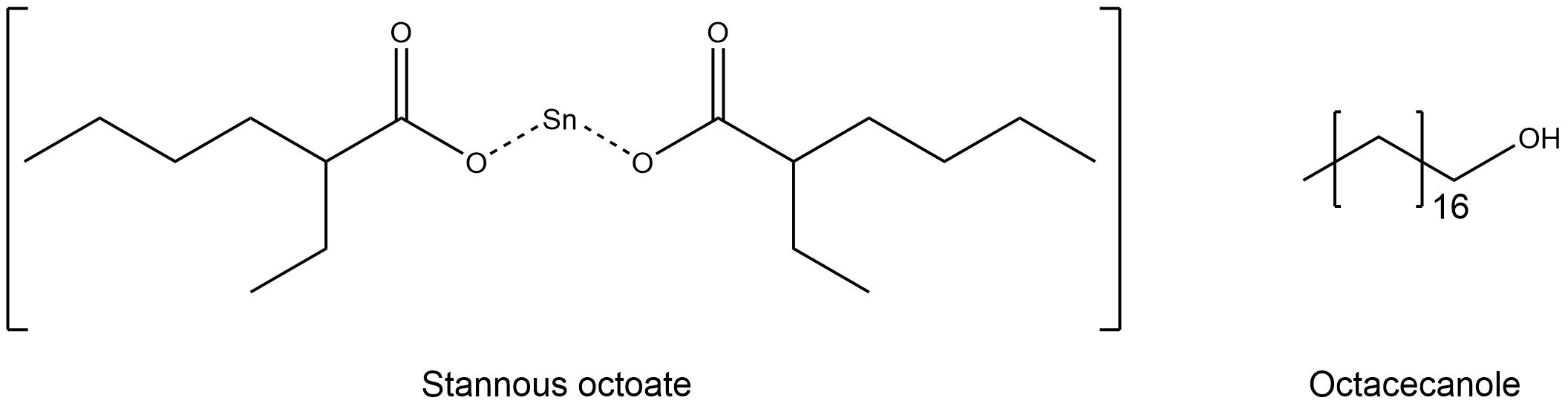

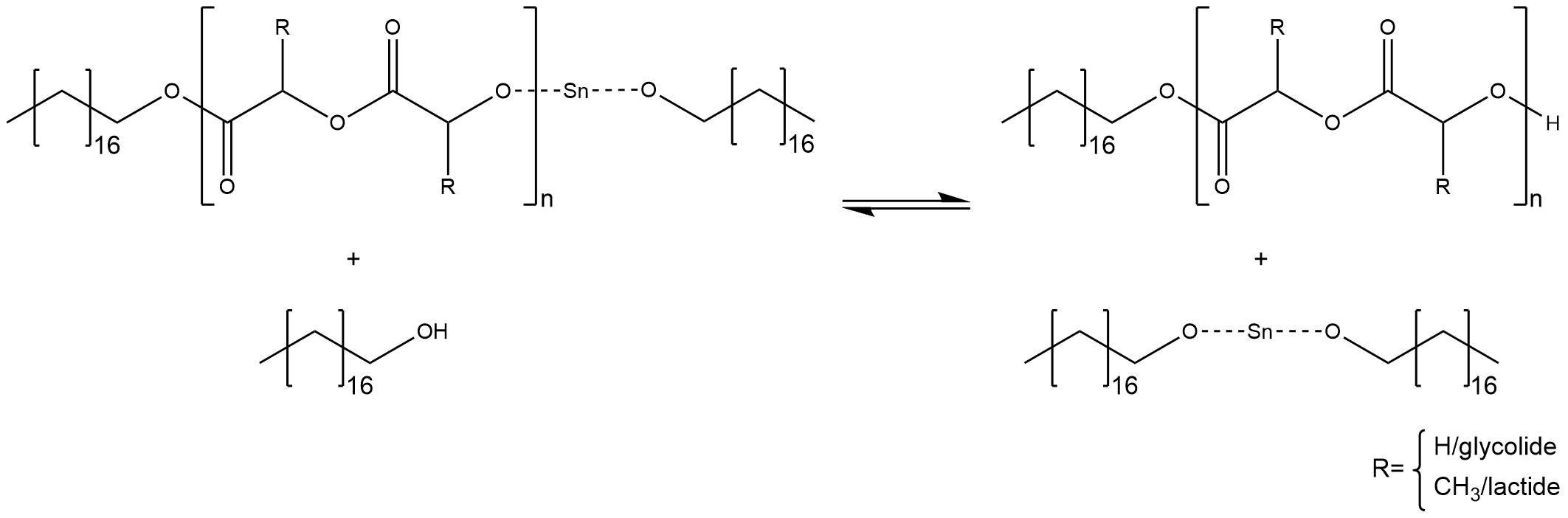

The anionic ring opening polymerization (ROP) takes place in the melt of the monomers. To start the formation of polymer chains an initiator and a co-initiator are used. For our mechanism we are using stannous octate [Sn(Oct)2] as the initiator and octadecanole as co-initiator.[2] (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Structure of stannous octoate (left) and the structure of octadecanole.

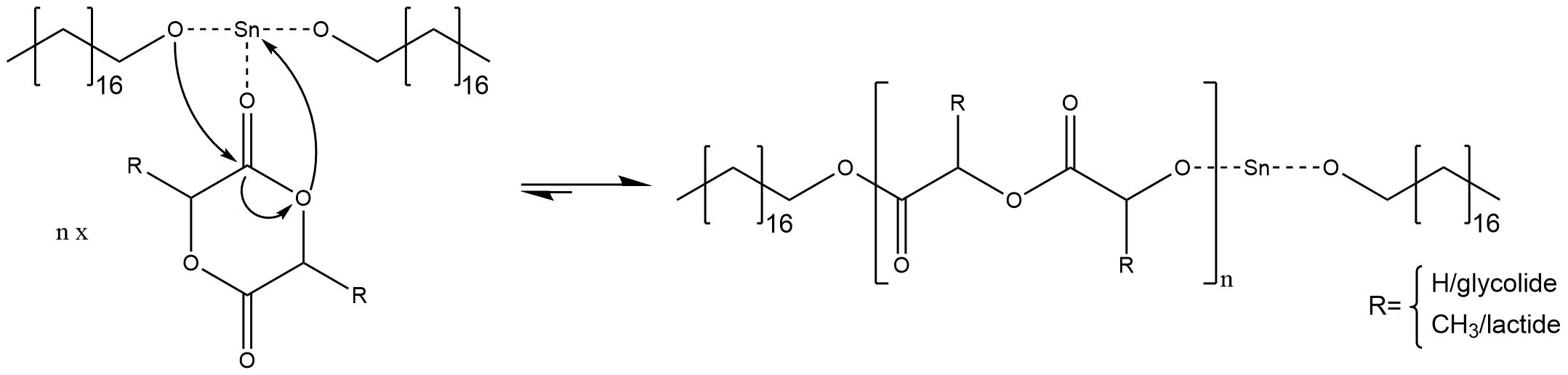

Befor the polymerization reaction starts, the initiator and co-initiator react with each other forming an alkoxide ion (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Activation of the coinitiator.

Following the activation of the co-initiator the ROP takes place. First the metal ion of the activated co-initiator coordinates on the double bonded oxygen of the cyclic ester. Thereby the electrophilic character of the carbonyl carbon atom increases. The alcoholate ion of stannous octoate attacks the carbon atom forming a tetrahedral intermediate. The collapse of the tetrahedral intermediate causes the opening of the cyclic ester. Hereby the tin alkoxide is regenerated (Figure 5).[3]

Figure 5: Mechanism of the anionic ring opening polymerization.

The repetition of this step leads to the growth of the polymer chains. Since there are no terminating steps involved, the chain growth has to be stopped manualy, e.g. by quenching the reaction by immersing it in ice water.[4] (Figure 6)

Figure 6: Termination reaction.

Through the presence of impurities like water and alcohol different side reactions can occour. Those impurities react with the tin-alkoxide at the end of a chain and substitutes the proton of the hydroxyl group. As a consequence, the free active co-initiator is regenerated, as shown in figure 7. The respective polymer chain cannot grow further, whereas the co-initiator can start a new ROP.

Figure 7: Side reaction at the end of a chain, caused by free alcohol molecules.

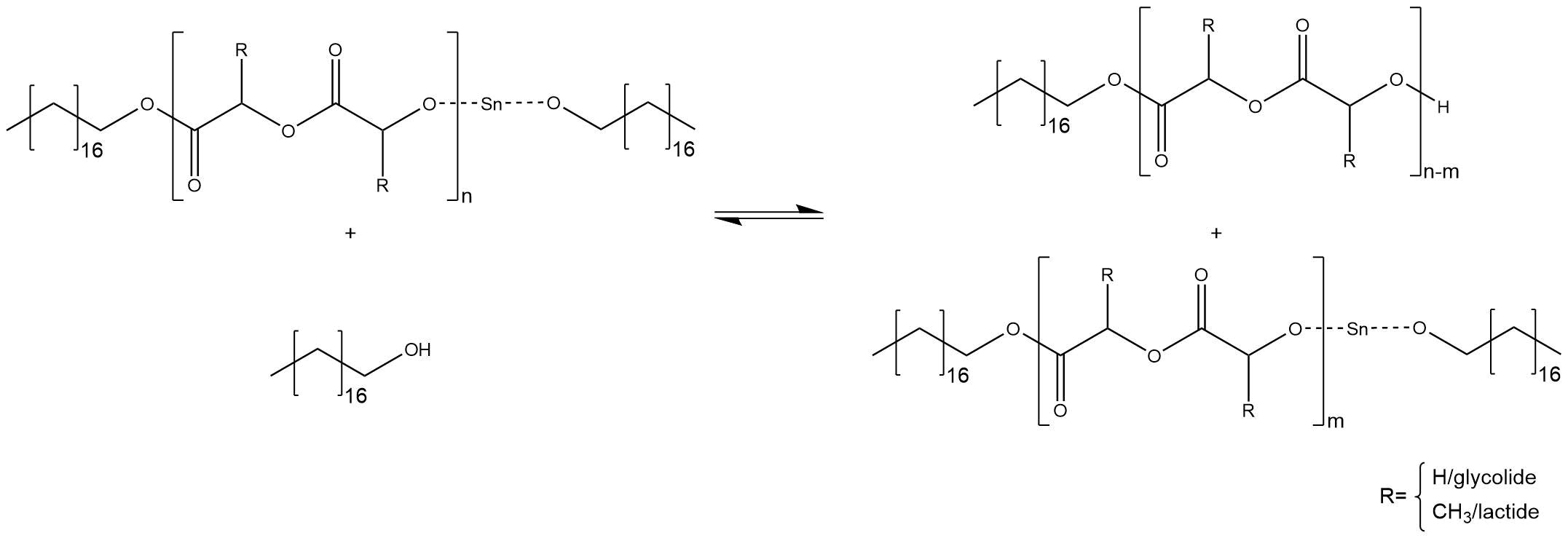

Another side reaction is the transesterification. The monomers are connected via ester bounds. Therefore, an alcohol can initiate a transesterification inside the polymer chain which leads to its separation, as shown in figure 8. The chain, which bonds the tin alkoxide, can grow further. The main problem of these transesterification is the fact that chains with different sizes are synthesized.

Figure 8: Side reaction inside a chain, caused by free alcohol molecules.

To remove impurities like moisture, which causes side reactions, a strong vacuum was applied. Through the addition of an inert gas atmosphere, ambient pressure is restored, preventing the evaporation of the monomers. Another source for free alcohol molecules is an excess of the co-initiator octadecanol. If the stoichiometric ratio between initiator and co-initiator is not balanced, free alcohol molecules remain in the melt and initiate side reactions as mentioned before.

Controlling the molecular weight

Every activated co-initiator starts one growing polymer chain. Statistically, every single chain grows at the same rate until the monomers are completely converted into polymers. Thus, it is possible to calculate the number of monomers inside the polymer chains, which should have approximately the same size. Increasing the ratio between initiator stannous octoate and monomers leads to the formation of smaller chains and by decreasing the ratio polymer chains with higher molecular weights are synthesised. To predict the molecular weight, a conversion of 100 % has to be provided. Another important aspect of the synthesis is the fact that the glycolide monomers are more reactive than the lactide monomers. Because of the less steric hindrance of glycolide, those monomers react faster than lactide. As a consequence, the glycolide monomers tend to form blocks inside the polymer. Those blocks influence the properties of the PLGA. The solubility of PLGA is worse and the crystallinity is higher. To prevent glycolide blocks, it is necessary to have a homogeneous reaction medium through strong stirring and conversion rates on nearly 100 %.

Degradation of PLGA

Earlier it was mentioned, that PLGA is a biodegradable plastic. The reason why PLGA is biodegradable, whereas many other plastics are not, is the special structure. Plastics without any reactive areas or bonds on its polymer chains, like saturated hydrocarbon polymers or worse polyfluorinated polymers are not biodegradable. These cannot degrade, because the water or enzymes of microorganisms do not have the possibility to cleave any bonds inside. Polyesters like PLGA have a backbone with ester groups in regular intervals. Each one of these ester bonds can be cleaved by water or by enzymes.

For PLGA, the degradation speed mainly depends on the ratio of monomers and the morphology of the polymer. Water has to diffuse inside the polymer to reach the reactive ester bonds. Therefore, a porous surface with gaps eases the diffusion of water, which causes a swelling of the polymer. After swelling the polymer starts to degrade into oligomers. The mechanism of the degradation is an ester hydrolysis.

The ratio of monomers is the property largely influencing the degradation. Lactide has two more methyl groups than glycolide. This has two consequences. First, the methyl groups are non-polar. Thus, they shield the polymer from water and water needs more time to penetrate the polymer structure. Accordingly, it applies the more lactide there is inside the polymer, the longer the time of degradation. The second reason is, that the carbonylic carbon atom of lactide is near by the methyl group. Therefore, water has less space to attack and the possibility of hydrolysis is smaller than in glycolide.

The oligomers further degrade into glycolic acid and lactic acid. Microorganisms can convert lactic acid and glycolic acid to CO2 and H2O. The form of the polymer influences the degradation through the size of its surface. If the polymer has a huge surface, there is more space for water to diffuse inside the polymer. However, if the density of the polymer is high, the surface of the polymer is smaller in relation to the mass of the polymer and it becomes more difficult for water to penetrate. [5].

Results and Discussion

Polymer Yields

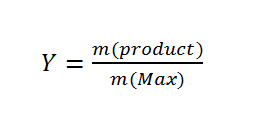

After the polymer was purified and dried, the polymer yields of the synthesis were determined. The products were weighed and the yield was calculated using the following equation.

Y= Yield, m(product)= mass of the product, m(max)= maximum achievable product mass

The maximal possible yield is approximately equal to the total mass of the monomers if a conversion rate of 100 % is achieved. The results of the calculation are listed in table 1.

Table 1: Used amounts of monomers and yields of synthesis (total and relative).

| Polymer | m (lactide) [g] | m (glycolide) [g] | Total Mass [g] | Total Yield [g] | Relative Yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA (I) | 10.810 | 2.901 | 13.7 | 2.703 | 19,72 |

| PLGA (II) | 13.13 | 5.26 | 18.43 | 3.306 | 17.94 |

For PLGA (I) we purified 100 % of our product and calculated the yield (shown in table 1). Since PLGA (II) was further used for nanosphere synthesis, total yield could not be determined.

As the yields in table 1 show, the relative yields are with 17.94 % and 19.72 % just about one fifth of the initial amount. This is caused by the increase of viscosity during synthesis, which makes magnetic stirring insufficient. Reactions were terminated when magnetic stirring stopped for reasons of reproducibility. To allow longer reaction times mechanical stirring would be necessary, which was unfortunately not available to us.

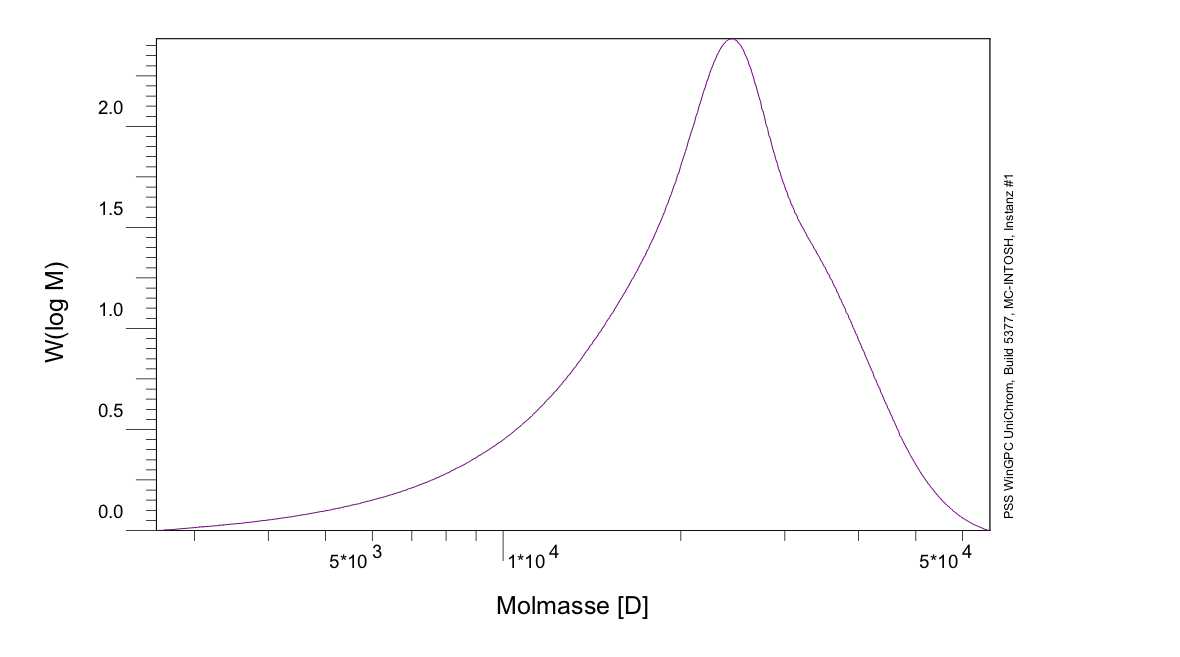

GPC Results

The expected molecular weight of PLGA (I) (ratio 75 %/25 %) was determined to be 361,669 g/mol, while the result of the GPC shows a molecular weight of 23,695 g/mol, as seen in figure 9, which means, that the chains are shorter than expected. Contrary to that, the expected molecular weight of PLGA (II) (ratio 67 %/33 %) was determined to be 2.106*106 g/mol, while the GPC result shows a molecular weight of 167.9*106 g/mol, which means, that in this case the chains are longer than expected. During an informative dialog with Evonik, they gave us the hint, that the magnetic stirring mechanism, we were using, is not sufficient enough to stir the reaction mix at higher viscosity. This leads to an affectation of the growth of the polymer chains, while the reaction mix solidified. To avoid this effect, a more sufficient stirring mechanism is necessary.

Figure 9: GPC of PLGA (I).

Furthermore they gave us the hint that the molecular weight, which was higher than expected, results on a deactivation of initiator molecules by water, leading the monomers to spread on less polymer chains, increasing their length. This can be avoided by working in an even more water-freed environment.

This improvements however are not possible to be implememted in our laboratory set up, because, we are able to work either with sufficient stirring devices or in a water free environment.

NMR-Spectroscopy

To analyze the ratios of our PLGA polymer, we used 1H-NMR spectroscopy. We normalized the integral of the CH-group of lactide to 1.

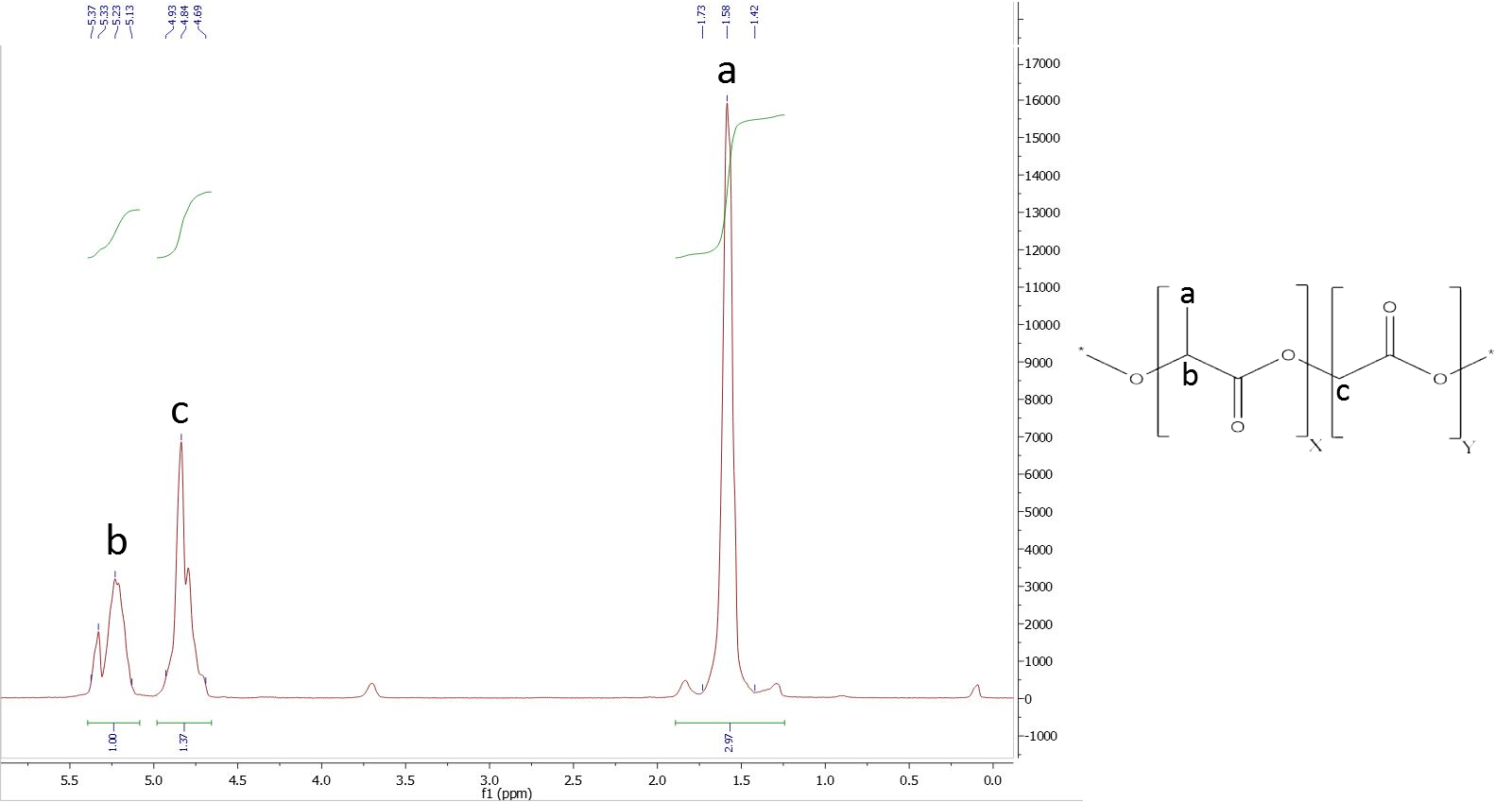

To determine the composition, it is necessary to assign a peak to at least one specific proton group of each monomer. Figure 1 shows the structure of PLGA and the obtained NMR spectrum, which is a typical PLGA spectrum. The peaks used for calculation of monomer ratios belong to the methyl protons of lactide with a shift of δ=1.44-1.69 ppm, and the glycolide protons with a shift of δ=4.69-4.93 ppm (Figure 10).

Figure 10: NMR of PLGA (I).

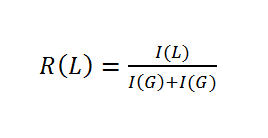

Ratios of incorporated monomers were than computed with equation 2:

The NMR spectrum reveals that the ratio of incorporated monomers in the synthesized polymer does not correspond to initial monomer concentrations. . The final amount of glycolide in PLGA is higher, supporting the conclusion that glycolide is much more reactive than lactide.

Table 2: Mole fractions of inserted monomers compared to the mole fraction inside the produced polymer. Here it is visible, that the ratios of the start and the end of the reaction are different. Moreover, an increase of the initial glycolide amount of about 10 % results in an almost two-fold gain in the final ratio.

| Polymer | Inserted monomer ratio [L/G] in % | Monomer ratio after synthesis [L/G] in % |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (I) | 75/25 | 59.13/40.87 |

| PLGA (II) | 66.6/33.3 | 38.76/61.24 |

The initial concentration of glycolide has significant impact on the ratio in the resulting polymer. If the amount is increased from 25 to 33 %, the ratio of incorporated monomers (L/G) switches from about 60/40 to 40/60.

To predict the resulting relations, despite these differing reactivities, we determined the co‑polymerization parameters for each monomer by using the obtained results. With these parameters, a kinetic model was designed that is able to calculate ratios inside the polymer, depending on the relative amounts of monomers used for synthesis. For further information about our modeling approach see here.

Outlook

PLGA and PLGC were produced using an insufficient magnetic stirring mechanism, which was not able to stir the reaction mixture at higher viscosity up to the end of the reaction. That led to a low conversion, which makes the results hardly reproducible. To avoid that, the reaction vessel needs to be designed in a way, which provides a continuous stirring all time throughout the reaction. The biggest difficulty lies in the achievement being able to have a mechanical stirring mechanism and pulling all humid atmospheric air out of the reaction vessel. Those conditions are not achievable with the laboratory equipment, which we can afford. With both conditions given, we would be able to get better reproducible results and more constant chain lengths. And with the polymers produced that way we would be also able to add additives and produce for example composite materials out of them.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cynthia D’Avila Carvalho Erbetta1, Ricardo José Alves2, Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(D,L-Lactide-co-Glycolide) Copolymer, Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology,2003.

- ↑ Yodthong Baimark and Robert Molloy, Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) Copolymers:Effects of Stannous Octoate Initiator and Diethylene Glycol Coinitiator Concentrations, ScienceAsia, 2004.

- ↑ Adam Kowalski, Andrzej Duda, Mechanism of Cyclic Ester Polymerization Initiated with Tin(II) Octoate. 2. Macromolecules Fitted with Tin(II) Alkoxide Species Observed Directly in MALDI-TOF Spectra, Macromolecules, 2000.

- ↑ Menem¸se K˙IREM˙ITC,˙I-GUM¨US¨¸DERELIOGLU,Synthesis, Characterization and in Vitro Degradation of Poly(DL-Lactide)/Poly(DL-Lactide-co-Glycolide),Turk J Chem, 1998

- ↑ Hirenkumar K. Makadia and Steven J. Siegel, Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier, Polymers 2011.