EXPERIMENTS

Our initial design idea was to detect a food pathogen with a biosensor that was integrated into the food that it was protecting. We considered using many different strains for our biosensor, our primary idea being to use an edible E. coli strain (Nissle 1917). E. coli Nissle 1917 is well-known as being a probiotic strain and has been marketed as such. However, after lots of consultation (read more about our Human Practices), our idea was refined: to use a strain native to cheese (Lactococcus lactis) that could detect a specific Listeria monocytogenes quorum signal (auto-inducing peptide; AIP), and would then alert the consumer to food contamination by changing colour.

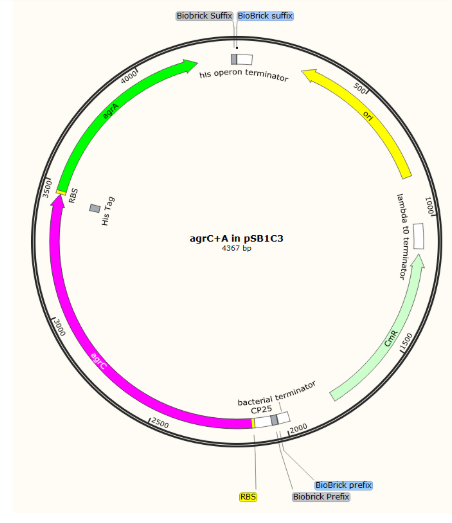

This led to the design of two main circuits (read more about our Parts): a detection circuit, which would detect the quorum signal and change colour, and a testing circuit, which would produce the AIP and allow us to test the detection circuit without having to work with the pathogenic L. monocytogenes. Ultimately, in our designs, we split the detection circuit into two devices as the whole circuit was too large to synthesise. One device (AgrA+C) produces the receptor histidine kinase and response regulator needed to detect the AIP and the other (PII) has a promoter that the response regulator binds to drive transcription and a reporter gene. We initially chose amilCP as our reporter gene as it is well-characterised in iGEM and produces a strong blue-purple pigment within 24 hours (in E. coli). Further investigation later led to the Glasgow iGEM 2016 wiki which suggested that amilCP may be unsuitable for expression in lactic acid bacteria due to acidic cellular conditions. In later constructs, we, therefore, used gFasPurple as our reporter gene as it was more representative of the colour we wanted to produce and did not have any known negative characteristics for our biosensor. We designed these circuits to be expressed in E. coli and L. lactis due to anticipating difficulties with an expression of membrane proteins, as well the ease of use of E. coli for DNA assembly.

Because it was important for our circuits to work in both E. coli and L. lactis, we needed promoters that would function well in both chassis. We found a library of such promoters in Jensen and Hammer’s 1998 paper and whilst they are already quantified, we wanted to try quantification with chromoproteins, both to see if this is a valid method of quantification and to gather more data for the model (read more about our Model). To this end, we designed two devices using these promoters; P15 and P25, and each consists of the related CP promoter (so CP15 for P15), an RBS (BBa_B0034), gfaspurple and terminators (BBa_B0010 and BBa_B0012).

To summarise:

Sequences IDT kindly sequenced for us.

All parts of the agr system were found in GenBank Accession number AL591973.1. Parts were kindly synthesised by IDT.

We aimed initially to clone all the parts into pSB1C3 and then join the two halves of the detection circuit together to form the complete circuit on one plasmid.

Initial parts in pSB1C3

Composite, complete detection circuit:

We initially attempted to clone our gBlocks into pSB1C3 through restriction enzyme digest of vector and insert with EcoRI and PstI and carrying out subsequent ligation of product. Our first attempts at this yielded no colonies after transformation. We felt that this could have been down to using a relatively small fragment to vector ratio and that by using a different approach of using an intermediary vector, we could allow the bacteria to replicate the fragment for us, saving both our IDT DNA stock and PCR reagents but allowing us to use a large fragment to vector ratio.

Following this line of thought, we cloned into pCRblunt using the Zero Blunt cloning kit. This worked well in comparison to our attempts at cloning straight into pSB1C3. We also were able to obtain a colony of P25 in pCRblunt vector which had begun to turn purple, which gave us confirmation that the promoters we had chosen were suitable for E. coli.

This is P25 in PCRblunt showing a purple colour in comparison to, normal coloured colonies.

Further EcoRI and PstI digest of our BioBricks in pCRblunt and ligation into pSB1C3 was challenging: we obtained one positive sequenced BioBrick in pSB1C3 which we have submitted to the registry: BBa_K2613743)

There was a mismatch in the sequence of agrD but this is probably a reading error rather than a mutation in the gene as the read was poor quality for this single base. This part represents the AIP production part of our circuit and as it was optimised to express in E. coli, we began testing.

We decided to run a protein expression experiment and western blot to verify that the construct was actually producing the AgrB protein. 750 μL of saturated overnight culture was added to 75 mL LB (1/100 dilution; cultures in triplicate) and grown for 1.5 hours, yielding the following growth:

pTE1059 is being used a positive control for visualisation of His-tagged protein and was kindly supplied to us by Marc Biarnes Carrera (Biarnes-Carrera et al., 2018). Though DH5ɑ cells expressing our BioBrick did not grow in 1.5 hours, BL21 cells expressing the same plasmid did grow well - as was to be expected - and were able to be induced (0, 50 nM and 100 nM ATc).

We hypothesise that in this case, the protein produced by the strain was toxic and was inhibiting growth as an expression of membrane proteins in E. coli can be challenging. pTet is known to have a degree of leaky basal expression which may have caused cell death. The high copy number of pSB1C3 may have been problematic in this case, and using a plasmid with lower copy number such as pTE1059 (15 copies per cell compared to ~300 copies of pSB1C3) may aid in protein production without over-taxing cells. If we had had more time we would have pursued this and carried out a growth curve over a longer period to investigate how strong growth was inhibited in strains carrying our plasmid.

We were unable to see the expression of our His-tagged AgrB at the expected size of 24.5kDa. As our DH5a cells carrying the plasmid had such low growth, we anticipated this was due to a high basal expression of the protein, which does not match our hypothesis here. If we had more time we would carry out further work using a Design of Experiments approach to optimise:

Temperature

Time

Nutrient sources

The concentration of inducer molecule

Strain - we could test a strain such as ArcticExpress which are useful for expressing soluble protein

To achieve visualisation of production of agrB in a robust strain such as BL21.

Future work

Our primary aim going forwards would be to successfully clone all our devices into a shuttle vector suitable for expression in E. coli and L. lactis, such as pNZ8048. Once this is achieved, we would use western blots and a Design of Experiments approach to quickly find optimal conditions for expressing our proteins.

We could then purify AIP produced by the AIP production device by known purification techniques or by purification by use of mini-inteins

Ji, Beavis and Novick, 1997Malone, Boles and Horswill, 2007

We would analyse the presence of AIP by HPLC-MS to both ensure that correctly modified AIP is produced by this system.

After, we could initially test the detection circuit with a high concentration of AIP to test whether our circuit works. Once we are sure that both parts do function as intended we would begin to refine the detection circuit’s sensitivity using our modelling to design new promoters with altered activity and to test their effects in silico to reduce the volume of wet lab work. Ultimately we would want to strike a balance between a fast detection time and a low (preferably 0) false positive rate.

Implementation of a positive feedback loop at this stage could both reduce the concentration of AIP that the device could detect and also, hopefully, increase the response time of the system.

As a final layer of testing, we would test the detection circuit in various kinds of soft cheese with actual Listeria monocytogenes, success here would be an ironclad proof of functionality. Once an effective maximum response time is achieved, we could progress in one of three possible directions:

1. Porting the system to other cheese making bacteria (e.g. Streptococcus thermophilus) which would allow our system to be used in more varieties of cheese.

2. Focus on producing a cell-free system, and as our system relies on membrane proteins, an approach to this could be through the production of minicells. These minicells would be unable to reproduce and so would be more useful in products such as processed meat (read more about our News analysis) .

3. Introduction of a Listeria-killing system to reduce the spread of the bacteria in large store-houses.

Ultimately, we would need to do a lot more research and human practices to decide which of these options would be more useful to consumers overall.

References

1. Ji, G., Beavis, R. and Novick, R. (1997). Bacterial Interference Caused by Autoinducing Peptide Variants. Science, 276(5321), pp.2027-2030.

2. Malone, C., Boles, B. and Horswill, A. (2007). Biosynthesis of Staphylococcus aureus Autoinducing Peptides by Using the Synechocystis DnaB Mini-Intein. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 73(19), pp.6036-6044.